Introduction

On 22 January 2025, a shooting at Antioch High School in Nashville, Tennessee, left one student dead and another injured. The 17-year-old perpetrator killed himself before the arrival of responding police.

The shooting shares considerable similarities with other lone-actor attacks linked with far-right accelerationism, including an attempt to livestream the violence, the shooter’s sharing of a manifesto and other media, and the glorification of previous terrorists. The attack likewise received significant media attention due to the seeming contradiction of the perpetrator being a Black individual and idolising white supremacist attackers.

The attacker’s interactions with extremist subcultures have already been examined thoroughly by scholars like Marc-André Argentino. In this Insight, I instead analyse the performative and identity-conferring elements of the shooting and the attack’s seeming ideologically contradictory aspects. I first provide an overview of the shooter’s participation in online communities. Then, I focus on the functioning of online anonymity and highlight its dual reinforcement within online extremist communities. Finally, I turn to the question of online anonymity in relation to performativity and lone-actor terrorism. I argue that, by deliberately identifying himself with past attackers via the use of digital tools, the perpetrator sought to replace his legal (i.e. racial, but also, more broadly, individual) identity with a ‘performed’ archetypal one.

Community, Anonymity, and Mediation

The perpetrator of the Antioch attack was active on multiple social media sites and forums. These included mainstream websites like X, Bluesky, Kick, YouTube, Pinterest, and multiple shock sites or niche forums sharing violent media and gore, including terrorist attack footage. My analysis of the shooter’s social media handles – at least 21 in total – highlights how he used usernames linked to various online extremist subcultures, primarily those associated with incel ideology and white supremacy, as well as references to past attackers. In the case of X, the shooter operated at least four accounts, as outlined in his manifesto. Moreover, the shooter admits to having visited and posted on websites like 4chan, where users are not required to have a dedicated username. Further demonstrating the shooter’s activity in various forums and online communities, the final part of the manifesto contains a discussion of admin policies and site moderation on a chan-like site. This point serves to show that the attacker was an original and “authentic” member of the site who knew its founders and earliest users rather than being a late adopter.

The use of multiple accounts, and often of several usernames on a single platform, appears to be dictated by the shooter’s preoccupation with ensuring anonymity. The attacker could adopt different user-identities by using multiple accounts with different handles on the same platform. This allowed him to dictate the pace and mode of engagements with the online communities he interacted with and retain ‘backup accounts’ to minimise the risk of being compromised. This seems to be both related to the realistic threat of being identified by authorities and that of in-group doxing. In his writings, the shooter details his preparation for the attack and generalises it into comprehensive infosec advice for possible copycats. His manifesto reiterates that ensuring anonymity is maintained is a key part of interacting with other users on online extremist spaces and warns against “honeypot” communities – groups set up by law enforcement to attract and “trap” extremists. This, notably, is contrasted with the shooter’s use of full names for past attackers and his providing links to their media, aiming at ensuring recognition and inspiring further violence.

On the Dual Necessity of Anonymity in Online Extremist Communities

In a 2019 paper analysing anonymity, Abigail Curlew sketches out the concept of “undisciplined performativity” to describe how anonymity shapes community interaction on social media. Her claim is that anonymity disentangles users from the constraints of their “legal identities” and results in new community-level constraints and expectations. The “belonging” of participants to a community is, therefore, equivalent to their performing certain expected roles.

In online extremist communities, platform structures enable anonymity—like the allowance of anonymous usernames or participation without personal details. This is reinforced by a shared expectation that users will respect each other’s anonymity and maintain their own. This norm is driven by the perceived threat, real or imagined, of police intervention.

This “strategic necessity” of online anonymity has implications for participants in online extremist spaces. As divulging personal details is taboo and risky, and cross-platform identification is complicated by the use of multiple accounts and handles, participants in extremist subcultures must rely on other identifiers. These include the use of niche language, term substitutions, or symbols that out-group observers cannot decode to ensure that their interlocutors are not bad actors.

The Antioch shooter projected an in-group status with his online behaviour through the constant performance of relevant identifiers. The shooter’s manifesto, as highlighted in the first section of the Insight, includes multiple pieces of so-called evidence of his commitment and ‘belonging’ to the communities he interacted with. The text includes extremely niche references, sometimes combined with insider terminology only accessible to other community members. Moreover, the manifesto and diary heavily plagiarise material from other shooters’ writings and contain long lists of attackers and extremist groups, further seeking to demonstrate the author’s claim of belonging.

Identity Performance for the Antioch Attacker

The shooter’s preoccupation with anonymity during the attack’s preparatory stages did not extend to the attack itself. On the contrary, before and even during the attack, he made extremely deliberate choices in terms of presentation and behaviour. These choices are not aimed at ensuring a degree of personal notoriety. Rather, they show both a preoccupation with ensuring he would be recognised as belonging to the in-group – with reference to the mostly closed online subcultures the shooter was part of – and an interest in controlling mainstream “outside” reporting on the shooting.

On one side, the attacker signalled an interest in his actions trickling down to mainstream discourse and being understood by wider society as not being isolated. On this, he wrote in his manifesto: “what’s important is that you film and photograph your efforts” and that “manifestos and livestreams push accelerationism back into the mainstream”. On the other hand, he encouraged his contacts to “spam” photos and footage of the attack within their shared online niche communities (specific messaging channels, for instance, are mentioned). In this sense, it is interesting that when using the second person in the manifesto, the shooter alternatively refers to “outsider” readers (such as possible copycats or journalists) and to (anonymous) mutuals on social media.

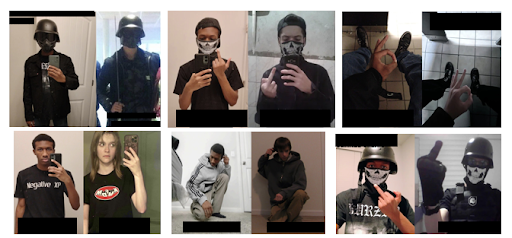

This is also evident in the extreme level of effort the shooter took to connect himself to previous lone-actor terrorist attacks. At multiple points, the attacker shared images of himself imitating the dress, poses, and mannerisms found in photographs of previous shooters (notably not only from an accelerationist milieu). These included the 2024 Turkey mosque attacker, the 2019 Suzano school shooter, the Trollhättan school stabber, the Isla Vista attacker, the Sandy Hook shooter, the Virginia Tech shooter, the 2019 El Paso shooter, and the Kerch Polytechnic shooter. Moreover, the Antioch attacker took multiple pictures, copying those shared by the Abundant Life shooter, including two in the minutes immediately before the attack.

Fig. 1: Side-by-side comparison of screenshots from the shooter’s X profiles and writings showing an attempt to copy past attacker’s posts, clothes, and gestures. Source: X

In addition, the shooter also used other digital tools to reinforce his identification with previous attackers directly. Footage circulating on social media shows videos allegedly recorded by the attacker on a VR video game, where he recreates the 2019 Christchurch Mosque attack, again deliberately placing himself in the role of the perpetrator. This footage, as well as other statements made by the attacker in his manifesto, underscores the ways in which extremist online subcultures, often catering to extremely young users, have adopted a logic overlap between POV attack footage and online gameplay videos.

Beyond Ideology: Performativity and Extremist Identity

This preoccupation with copying (in a quasi-cosplay-like manner) several past attackers can only partly be explained by the shooter’s interest in incel discourses. The manifesto heavily focuses on “looks” and “aesthetics”, as well as physical training and fitness; in fact, it somewhat contradicts them. Incels are mostly preoccupied with the individual, hence the obsessive drive to “scientifically” compare looks. Instead, through his meticulous study of past shooters’ photos and attacks, the attacker appears to shape his identity into an “ideal” lone actor terrorist — an amalgamation of those who came before him.

This represents a step beyond ideology and legal identity. As highlighted in the introduction, the Antioch shooter was a Black teenager, and therefore, his identity was contradictory to the stated ideological motive for the attack. The shooter shows awareness of this and, in parts of the manifesto, remarks how the perpetrators of previous far-right lone actor attacks would have likely not associated with him and would not have recognised his actions.

Nevertheless, I argue that the dual reinforcement of anonymity is what allowed the shooter to go beyond these contradictions. As highlighted by the performative aspects of both the preparatory stage (writing a manifesto and diary, recreating past shootings and shooters’ pictures) and the attack (adopting specific weapons and dress, live streaming), the Antioch shooter’s actions resemble a real-life projection of a set of online community expectations. The attack is not just a personal affair but takes a coherent meaning as a performance that references a dispersed, online collective. In minimising and dismissing his individual “claim to fame” as an attacker and instead identifying himself with an “archetype” of the accelerationist lone actor terrorist, the Antioch attacker portrayed himself as an anonymised character, a repeated version in a chain of attackers.

Research and Policy Implications

While the 2019 Christchurch Mosque shooting has become a defining instance of contemporary lone-actor terrorism that has driven multiple copycat attacks, the recent Antioch shooting further highlights how lone-actor violence operates differently from traditional group-based terrorism, following its own distinct logic rather than a clear, organised strategy.

In generating, compiling, editing, and broadcasting large quantities of material, the Antioch shooter sought to mould himself to an idolised archetype of what he thought a lone-actor terrorist should be. This identification heavily relied on technological and digital features. Anonymity allowed him to go beyond his legal identity and to claim a sense of belonging to dispersed online communities; POV video games allowed him to allegedly recreate the Christchurch attack (the “quintessential” lone actor attack); social media and streaming platforms further gave him the opportunity to imitate his “predecessors”. From gradual self-radicalisation to that of action, mediation and technology were essential to forming the meaning of the Antioch attack for its perpetrator.

In the process of writing this Insight, something unusual occurred. On 26 February, the “reels” tabs of thousands of Instagram users (including my own) were flooded with extreme gore and other violent material. This prompted Meta, Instagram’s parent company, to apologise, citing an “error” in the algorithm. While some commentators speculated this was due to some recent changes in Meta’s moderation policy, it is unlikely that the closely guarded “black box” recommendations algorithm will provide many answers to researchers.

The 26 February malfunction creates an opportunity for reflection on the Antioch case. As mentioned, the shooter frequented multiple online platforms and moved fluidly between them. In detailing his radicalisation journey, he never really provides a clear step-by-step or pipeline model for his progression. Rather, he highlights how different content, from the mundane to the radical to the simply violent, with no ideological connotation, interact and overlap with no solution of cause. All of the content, no matter how extreme it may appear to outside observers, is left undifferentiated and treated equally.

The error of Instagram’s algorithm, in my view, provided a clear demonstration of this element: the difference and interval between a harmless cooking tutorial or book review and footage of a terrorist attack is as simple as a swipe on a phone screen. For policymakers and researchers, this further demonstrates the importance of focusing on the medium itself, rather than only the content, to understand and combat lone-actor terrorism and extremism. In particular, it is clear from the Instagram case that recommendation algorithms can and do work in unexpected and possibly dangerous ways.

Algorithms on social media are meant to maximise user’s screen time and to aid the generation of user data that can be sold to advertisers. This imperative is fundamental and takes precedence in shaping platform functions. The result, however, is blindness to the type of content recommended. As long as it drives engagement, algorithms can leverage feelings of anger, anxiety or depression, with possibly harmful results. Moderation, even if using advanced Artificial Intelligence or considerable manpower capable of processing large volumes of information, is bound to be reactive, and possibly ineffective. While platform moderation remains important, policymakers and private sector leaders should be willing to take bolder steps in questioning the structural and economic drivers of online engagement and how they shape and impact real-life behaviour and social interactions.

Manfredi Pozzoli is a master’s graduate in International Affairs at LSE and SciencesPo Paris, as well as a research fellow at Think Tank Trinità dei Monti, in Rome. His research interests include the intersection of social media and terrorism, especially in the context of Europe and North America.