Introduction

In recent years, far‐right extremist tactics have taken a turn toward targeting critical infrastructure — a renewed trend rooted in a longstanding history of such attacks. In 2022, three men pleaded guilty to a plot to attack power grids in the United States. In 2023, CNN obtained a bulletin made by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) that warned against the rise in sharing of instructions on how to attack critical infrastructure by far-right extremists. Furthermore, in July 2024, a man was arrested in New Jersey after plotting to attack an electrical grid in the state.

These incidents, among others, underscore a broader pattern within the far-right extremist ecosystem, particularly among militant accelerationist groups. One such group, the Terrorgram Collective, which is named for its activity on Telegram, has emerged as a significant player in this landscape. This past September, two ideological leaders of the Terrorgram Collective terror group were jailed. Moreover, three men belonging to the same terrorist group were proscribed as Specially Designated Global Terrorists by the US Department of State in January 2025. This Insight will examine three publications of the Terrorgram Collective — in part using word frequency analysis — to enhance the understanding of infrastructure attacks.

How Terrorgram Collective Spreads Its Message

To this day, three main written publications have been published by Terrorgram Collective: Do It for the Gram [DIFG], Militant Accelerationism [MA], and Hard Reset [HR]. All three publications promote the ideology of militant accelerationism and were published on Telegram between 2021 and 2022. It is important to note that “militant accelerationism is a set of tactics and strategies designed to put pressure on and exacerbate latent social divisions, often through violence, thus hastening societal collapse,” according to the Accelerationist Research Consortium. In the minds of militant accelerationists, societal collapse is the only way to purge it of its decadence and build a new white ethnostate. In addition to promoting notorious lone-wolf mass shootings and demonisations of migrants, LGBTQ, Jews and people of colour, the latest publication, HR, heavily advocates for attacks on critical infrastructure as another means to accelerate the collapse of society.

While DIFG and MA focus on written text, with MA adding visual content, HR enhances the visual side of the publication so that each page can be seen as a propaganda poster, with some exceptions of larger contributions spanning several pages. It is unclear if these publications are still available on Telegram as most of the channels supporting Terrogram Collective are closed, and one needs to be invited to a chat to see the content within them. Therefore, it can be argued that the publications have had minimal spread throughout open-to-public channels on Telegram. Moreover, the publications were promoted mainly by a few individuals, most likely their authors, and not by the masses. Following the attack on the U.S. Capitol on 6 January 2021, Telegram started progressively removing “Terrorgram” channels. When asked directly, the Telegram press team re-confirmed this statement: “Telegram removed several channels that used variations of the ‘Terrorgram’ name when they were discovered years ago. Similar content is banned whenever it appears.” Even if the texts are now hidden behind closed channels or deleted from Telegram, their influence may endure. These messages may continue circulating within private networks or on the public Internet, extending their reach beyond the Telegram platform.

Figure 1: The Statement of the Telegram Press Team

The (R)evolution of Saboteurism

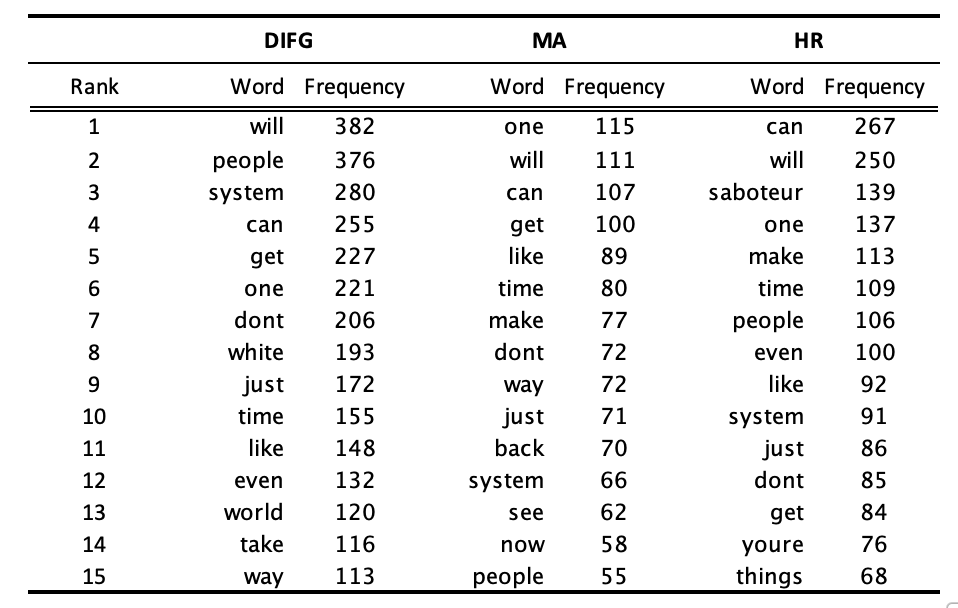

Word frequency analysis was used to examine all three written documents of Terrorgram Collective. The result is shown in Figure 2. When we exclude common stop words (insignificant words like determiners) and focus on content words, the most frequently used term in DIFG is “people”, in MA, it is “system”. However, most notably, in HR, the word ‘saboteur’ appears 139 times per publication. Additionally, the word “sabotage” appears 46 times in HR. The saboteur theme emerged abruptly, as neither of these two words appears in the top 100 words of DIFG and MA. Therefore, it seems that it is a deliberate strategy shift within the Terrogram Collective. The authors calculatedly chose to use the word “saboteur” as much as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Word Frequency Analysis

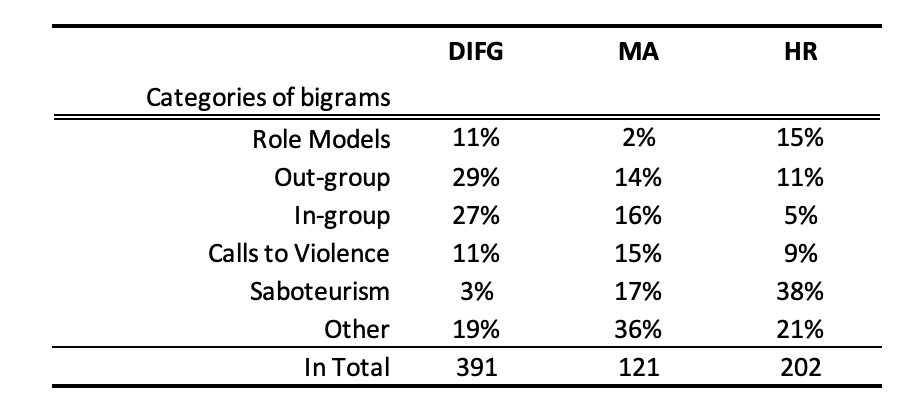

This transformation can also be seen in another method called bigram analysis. In other words, bigram is a sequence of two consecutive words (like “industrial system). As shown in Figure 3, the bigrams are classified into six distinct categories. While the first four categories are typical for analysing terrorist content, the fifth one — labelled “saboteurism”— stands out. This category essentially functions as a tactical playbook, offering readers concrete advice on planning attacks at both tactical and operational levels. Examples include bigrams such as “wear mask,” “surprise elements,” “electrical chainsaws,” and “power lines”. By advocating sabotage, the group seeks to destabilise state functions and thus accelerate societal collapse as militant accelerationism ideology dictates. In other words, each attack against critical infrastructure, or even vandalism, is aimed to enhance the chaos within current society and serve as another catalyst for total breakdown.

Figure 3: The Analysis of Bigrams

The emergence of saboteurism as a central theme in HR highlights a profound tactical evolution within the Terrorgram Collective that may produce actual attacks on infrastructure, as described in the introduction. The stark absence of “saboteur” and similar words in earlier publications, followed by their sudden prominence, suggests an intentional narrative shift inside the Terrorgram Collective. In HR, one of the contributors wrote: “Who am I, a saboteur”. This Insight argues that the rise of the term ‘saboteur’ is not merely another tactic to accelerate societal collapse but also serves another purpose, which is explored below.

Saboteur Mythos as a Form of Radicalisation

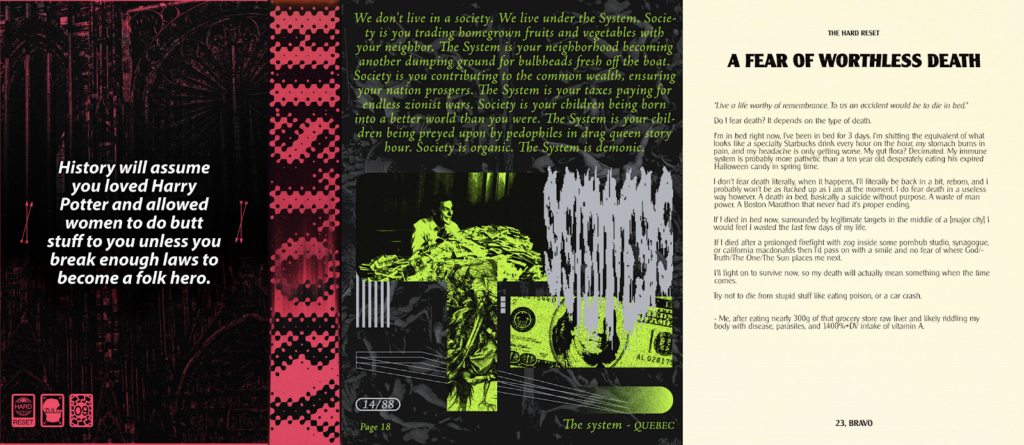

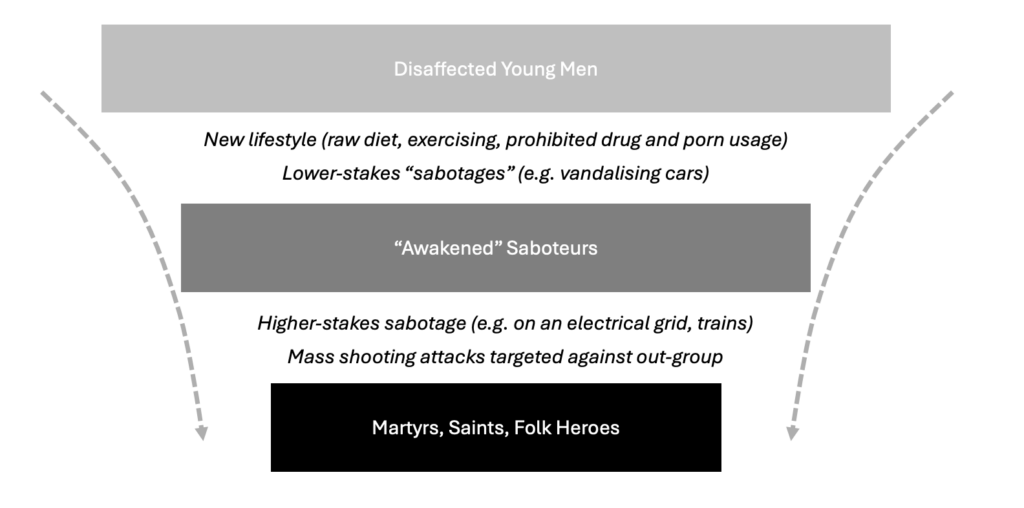

By incorporating the element of sabotage into the narrative, the collective presents a potential bridge between passive engagement and direct action. In doing so, the authors of the Terrorgram collective outline a conceptual framework that conveys a three-step process into the militant accelerationist milieu. Firstly, the reader is presented with their hypothetical dire situation (Figure 4). Pages portray Western society (“The System”) as an unnatural, demonic force that is robbing accelerationist adherents of their presumed birthright. The humiliation of the reader is also part of the process, as one of the pages shows. It taps into dissatisfaction with modern lifestyles, fostering self-pity and leading readers toward a more desperate mindset. This creates the illusion of empathy, paving the way for the Terrorgram Collective to present its strategy for reclaiming control.

Figure 4: Three Examples of Pages from Hard Reset – Dissatisfaction Young Men and Evil System Narrative

The following step is to introduce readers to the so-called enhanced lifestyle widely promoted in far-right circles. This core element ties together the extremist narrative with the broader messaging strategies of some far-right influencers (raw food diet, extensive fitness, among others). For example, using drugs (mainly marijuana) is strongly prohibited in the realms of militant accelerationism, according to Terrorgram Collective: “If you smoke weed, you will become satisfied with the world the way it is,” one of the pages says. Other aspects that are pushed by this group are working out excessively, eating a raw diet, and intensive physical training. The goal is to transform oneself into a hypermasculine saboteur. The saboteur’s symbolic value lies in its aura of ‘coolness,’ offering readers an escape from everyday life.

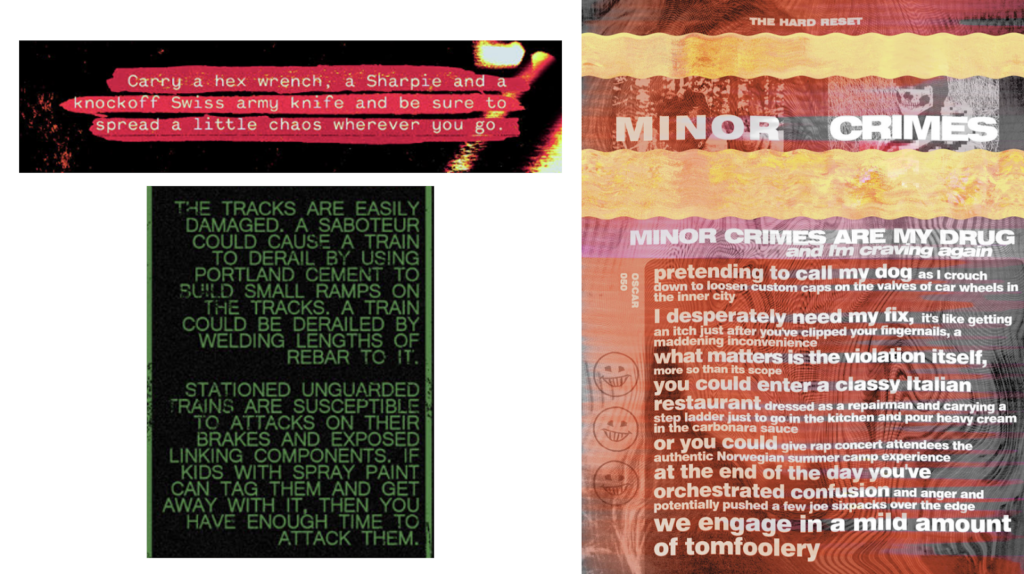

Subsequently, saboteurism creates opportunities for engaging in small-scale attacks on infrastructure, serving as an easy entry point into violent acts and, in a way, ‘awakening’ the passive followers. The saboteur myth portrays acts of sabotage as a noble, defiant stand against an oppressive system. These attacks often carry lower immediate risks compared to more overt or large-scale violent actions, making them an appealing starting point for individuals seeking to gain experience in violent extremism. The types of sabotage span from vandalising cars by slashing tyres and derailing trains to attacks on electrical infrastructure. All of these are supported by manuals with varying levels of detail, from satirical texts to serious instructions. This aspect helps build upon a decentralised and leaderless organisation connected only by these publications and new encrypted message apps such as Telegram.

By engaging in these activities, individuals new to militant accelerationism potentially improve their tactical skills, test their ability to act undercover, and, perhaps most importantly, build confidence in carrying out more destructive actions. There have been multiple instances of direct influence between terrorist plots and attacks and Terrorgram. One notable plot involved a man convicted of plotting to blow up a state power grid in the US.

In the eyes of the Terrorgram Collective, sabotage hardens the personality and prepares followers to attack human beings. Moreover, these sabotages are discursively constructed as another means of bringing collapse to modern society. Examples of these encouragements can be seen in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Progression from Low-Stakes Violence Encouragement to Intensified Violent Rhetoric

Following these extreme actions, adherents are officially recognised as saboteurs, and they can continue with the next phase – infamy as folk heroes or saints. Militant accelerationists see themselves as underdog heroes who are saving the white race from an oppressive system.

The Terrogram Collective remains steadfast in its attacks against members of the perceived out-group (such as immigrants, people of colour, LGBTQ+ people and more). While the end goal remains the same—the systematic collapse of modern society through acts of terrorism—the process is now framed as a transformative journey. Followers of Terrogram Collective are encouraged to refine their methods with the help of sabotages and thus maximise the chaos they can inflict throughout their radicalisation journey. Theoretically, it eases the journey by exposing oneself to lower-stake violence before preparing for a mass extremist attack.

Figure 6: The Schematic Visualisation of Terrorgram Collective Journey

Conclusion and recommendations

This analysis has showcased the deliberate shift in the Terrorgram Collective’s publication and provided likely reasons for that shift. The group’s ideological leaders aim to guide readers through a transformational journey from disaffected young men to saboteurs and, ultimately, to so-called Saints. The shift introduces the ‘saboteur’ as a crucial midpoint, which lowers the threshold for engagement in violence. By easing into the accelerationist milieu with smaller-scale harms and attacks, the pathway to larger acts of sabotage becomes more accessible

Furthermore, the last publication, HR, offers the largest and most developed collection of instructional materials on various sabotages of all three publications to support this symbolic transformation. Despite the recent prosecution of key figures within the Terrorgram Collective and its designation as a terrorist organisation by the US and the UK, the group’s publications remain accessible online, continuing to pose a significant threat by influencing potential extremists even when the original group is dissolved.

Building on these findings, two main recommendations can be made. Firstly, technology companies should reimagine content moderation to encompass the saboteur shift within militant accelerationism. This update might include keywords intrinsically connected to saboteurs, along with a contextual understanding of the shared content. Another approach could involve developing a counter-narrative around sabotages that could highlight the real-world consequences of sabotages causing collateral damage to the very communities that the Terrorgram Collective claims to protect. These counter-narratives might be promoted via recommendation algorithms so that viewers of extremist content would be exposed to them.

Additionally, the latest publication, HR, heavily emphasises the visual aspect, with most pages resembling posters. Therefore, extensive databases of these pages from various publications and manifestos can be created to ensure the minimisation of dissemination (such as GIFCT’s Hash-Sharing Database). This would ensure that participating tech companies have the resources to adjudicate violative content or narratives on their platforms properly.

Adam Frolík holds an MA in Security Studies from Charles University, specializing in the impact of emerging technologies. His research interests include far-right extremism and new technology.