Introduction

Large online retailers have long faced criticism for their failure to proactively remove extremist content from their platforms, from propaganda texts like The Turner Diaries to merchandise associated with violent extremist organisations. Critiques of these platforms are partly driven by the fact that many extremists rely on the profits of online merchandise sales to sustain their networks. Indeed, researchers from the Institute for Strategic Dialogue have found that several major e-commerce sites provide “the infrastructure for harmful actors to both reach a larger audience and to fund their operations.”

Even as extremists continue to leverage online merchandise sales to finance their activities, a separate challenge exists on e-commerce platforms: the sale of hateful products by storefronts with no apparent connection to extremists. What might prompt an average merchandiser to contribute to the spread of extremist symbols? This Insight examines an e-commerce practice known as dropshipping—when a merchant sells products without keeping an inventory—and explores its relationship to the presence of white supremacist merchandise on Amazon.

Ongoing Moderation Failures

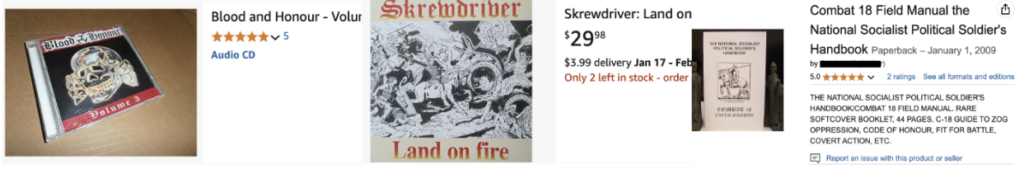

At the time of this writing, Amazon customers can still find merchandise associated with designated terrorist entities. CDs from Blood & Honour, an international neo-Nazi network that emerged out of the 20th-century white power music scene, remain available for purchase, along with a (currently out of stock) Combat 18 field manual. Even more widespread is merchandise related to Blood & Honour founder Ian Stuart Donaldson’s white power band Skrewdriver. Of note, the Government of Canada listed both Blood & Honour and Combat 18 as terrorist entities in 2019 and the United Kingdom announced a full asset freeze against Blood & Honour on 8 January 2025. (The latter action is distinct from the UK Home Office’s proscription authorities.)

In these cases, the sellers appear to knowingly profit from the sale of hate, with one merchant clearly specialising in the distribution of segregationist and neo-Nazi music. The ongoing presence of this content reflects some basic failures by Amazon to remove content associated with violent extremist movements. It also affirms Helen Young and Geoff Boucher’s 2023 finding that far-right extremist content remained an issue on Amazon “despite the removal of a handful of signature terrorist titles from inventory in 2021.”

Figure 1. Examples of white supremacist merchandise currently available on Amazon

Independent Dropshippers and Extremist Merchandise

Beyond these more familiar challenges associated with the removal of products in violation of platform terms of service, it appears that extremist e-commerce is also evolving alongside the growth of the dropshipping industry. In short, hateful symbols are being swept up in high-volume online retail schemes, leading to their sale on Amazon.

Dropshipping is a decades-old business model that has accelerated considerably in recent years. This practice, according to Vox’s Terry Nguyen, “is a way for retailers to fulfill customer orders. After a customer purchases a product…the order is shipped directly from the wholesale supplier to their home, so the retailer doesn’t have to keep inventory on hand.” Large companies pioneered the practice, and it was eventually adopted by e-commerce retailers like Wayfair. More recently, however, independent sellers have increasingly taken up the fulfilment method. An indication of the trend’s popularity, e-commerce giants like Shopify and Amazon have published dropshipping guidelines and keys to success for potential merchants.

The practice, however, is not without its drawbacks, as e-commerce platforms themselves acknowledge. Indeed, as one statewide consumer protection agency notes, the practice is marketed as a “get-rich-quick” scheme for novice entrepreneurs, but it comes with risks along the supply chain. And though it can be difficult to determine with certainty whether any given Amazon seller relies on dropshipping methods, telltale indicators include the use of stock photos on the product page, common product descriptions across item listings, and the sale of identical products by overseas retail giants like AliExpress.

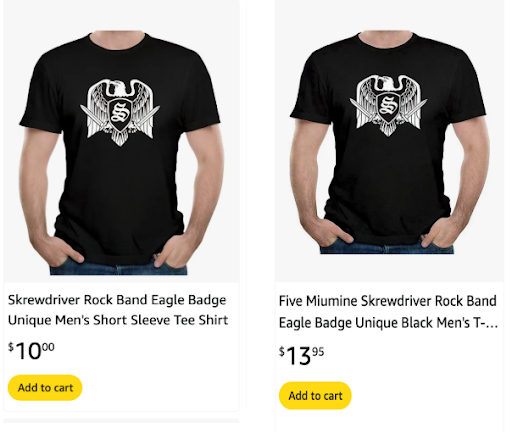

The overall merits of dropshipping aside, it appears that many sellers are relying on this practice to promote the sale of extremist and hateful merchandise. For example, one Amazon seller of rock-related merchandise offers t-shirts featuring the Skrewdriver logo, alongside innocuous bands like The Kinks and Whitesnake. This storefront, however, is only one of several sellers offering Screwdriver merchandise on the platform. Elsewhere, customers can purchase shirts carrying the symbols of Peste Noire, a French national socialist black metal band whose songs include “Aryan Supremacy” and “Les Camps de la Mort” (The Death Camps). These products clearly appear to violate Amazon’s policies that “prohibit the sale of products that promote, incite, or glorify hatred, violence, racial, sexual, or religious intolerance or promote organisations with such views.”

Figure 2. Two identical products from separate Amazon sellers featuring the logo of the white power band Skrewdriver

Outside the realm of white power music, Amazon shoppers can also find a bumper sticker carrying the name and logo of the Misanthropic Division, a neo-Nazi network active across Europe and beyond beginning in the 2010s. In addition, a storefront offers a range of products related to the Diagolon movement, a Canadian network notorious for its proliferation of extremist rhetoric. According to the Global Project Against Hate and Extremism, “Diagolon’s leaders and members openly post pro-Nazi, anti-LGBTQ+, antisemitic, and racist content on their social media channels, and have taken their bigotry to the streets by organizing events and protesting the LGBTQ+ community.”

In nearly all of these cases, the associated sellers do not appear to have a vested interest in the proliferation of extremist content. These products are listed by storefronts that also carry a wide range of banal merchandise, including national flags, HVAC insulation materials, and “I’d Rather Be Gardening” hats—suggesting the hateful merchandise may just be one product swept up in a high-inventory dropshipping operation. A search of relevant product images and descriptions also yields results for comparable merchandise at overseas wholesalers, the source of origin for many drop-shipped items.

Considering Radicalisation Risks

If extremists don’t appear to be directly marketing or profiting from apparent dropshipping operations, why should platforms and extremism researchers care about this trend? Firstly, the commingling of extremist merchandise with mainstream products lowers the barrier to entry for exposure to hateful symbols, narratives, and ideologies. In contrast to online fashion outlets such as Will2Rise, which explicitly caters to members of the Active Clubs network, consumers need not intentionally seek out extremist content while shopping on Amazon. As noted, products associated with extremist movements exist alongside harmless merchandise. The integration of these products contributes to the normalisation of extremist symbols and risks introducing these products to unwitting customers. As Cynthia Miller-Idriss writes in Hate in the Homeland, “hate clothing can expose consumers to extremist opinions, nudging ideological views on immigration, religion, violence, and gun control toward the extremist fringe while opening the door to further engagement and more dangerous actions.”

Moreover, the presence of extremist merchandise on Amazon provides a secondary market for these products, away from the scrutiny often placed on outlets and brands that specifically market products to finance a given extremist movement. Though payment processors and crowdfunding platforms typically adopt a reactive posture to such outlets, the presence of a backup option on Amazon will undermine even belated efforts to mitigate the spread of extremist merchandise.

Policy Implications and Mitigation Opportunities

Amazon should target its moderation and intervention not only at extremist sellers seeking to merchandise their own movement but also at opportunistic storefronts selling such a wide range of products that they (perhaps inadvertently) contribute to the proliferation of hate symbols. Given the scope of the problem, these interventions will require regular updates to Amazon’s internal datasets of extremist symbology, the continued use of machine learning and automation to assist in detecting code of conduct violations, and responsive human reviewers to adjudicate customer flags. Moreover, Amazon and other industry leaders should examine the extent to which sellers’ reliance on artificial intelligence to generate product titles, descriptions, and images are contributing to the problem of extremism on their platforms.

These mitigation efforts should include close attention to similar e-commerce companies in order to learn from mistakes across the industry. For example, Walmart faced pressure in late 2024 after Rolling Stone reported that the company had allowed third-party retailers to sell two separate Skrewdriver t-shirts on their website. This incident should have provided Amazon the opportunity to review its own holdings and take action against similar merchandise, but products featuring the same white power band still exist on the platform today.

Bearing in mind the likelihood that some storefronts may not even be aware that they are selling extremist merchandise, Amazon should take steps to inform and educate those in violation of their terms of service. If it does not do so already, Amazon might consider adopting a strikes-based approach applied in other Trust and Safety contexts, rather than resorting to immediate account bans. Improved moderation will also require clear guidance for borderline content such as merchandise emblazoned with “No Lives Matter,” a slogan adopted by a niche but increasingly concerning accelerationist subculture.

Outside the context of Amazon—and considering the European Commission’s ongoing investigation of AliExpress for potential violations of the Digital Services Act—policymakers might also consider opportunities to mitigate the presence of extremist products on the wholesalers that often feed into dropshipping schemes. By addressing this challenge closer to the beginning of the supply chain, officials may be able to affect downstream benefits that span multiple platforms. As a member of both the Christchurch Call community and the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism, Amazon holds a particular responsibility to rid its platform of extremist merchandise.

Regardless of the specific direction taken to overcome these challenges, the status quo continues to be inadequate. As extremists regain footing on mainstream online platforms , the removal of extremist symbols from the largest online retailer in the world remains a critically important task.

Joseph Stabile is a researcher of political violence and white supremacist extremism. He previously worked as a policy strategist at MITRE, a federally funded R&D center, where he conducted research and provided strategic planning support to the US government. Before joining MITRE, he worked as a research assistant at Georgetown University’s Center for Security Studies and fellow at National Security Action. His writing can be found at outlets such as Just Security, Inkstick Media, and the George Washington Program on Extremism.