Introduction

This Insight explores the evolving nature of the Baloch separatist insurgency in Pakistan, with a particular focus on how militant groups like the Baloch Liberation Army (BLA) have used platforms such as Rumble and Telegram to disseminate propaganda, project their guerilla capabilities, and sustain public interest in their militant activities. It also analyses the extremist group’s messaging strategies, the role of encrypted communication tools in bypassing traditional media gatekeepers, the challenges posed by cross-platform information sharing and the implications for Pakistan’s counter-insurgency efforts.

On 3 September 2024, the BLA, a separatist militant group fighting for an independent state in Balochistan, Pakistan’s largest and most marginalised province, shared a video on its Telegram channel. It begins by showing a dummy paramilitary base, with its layout carefully mapped out. It includes miniaturized structures, vehicles, a walkway, and a small replica of a helicopter. The video also features the leader of the mission, with a stick in hand as he briefs his comrades. The camera then shifts to focus on one of the two gates of the mock base, where an image of Mahal Baloch, a female suicide bomber, pops up. A few moments later, a silver car parked outside the gate explodes, spilling a plume of smoke and dust into the air. Following this, a new version of Bella Ciao, rendered in the Balochi language, is played with lyrics glorifying the Baloch militants. Later on, the video transitions to red spots on a Google map, marking the districts targeted in attacks, followed by raw footage of actual assaults.

In the video, the BLA frames its armed struggle as a liberation movement aimed at securing Balochistan’s independence. Its propaganda invokes themes of self-sacrifice for a broader political cause and a legitimate fight against exploitation, particularly in the context of projects like the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Moreover, the video serves as a tool for further recruitment as it appeals to disaffected youth to participate in the armed struggle to reclaim Baloch rights.

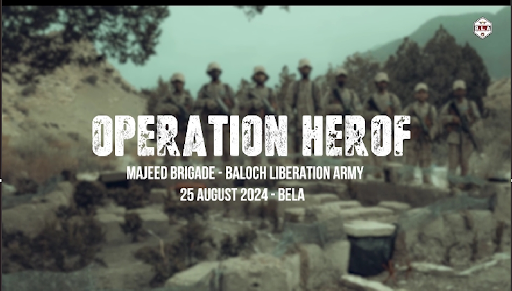

Figure 1: Screenshot from the video released by the BLA a week after Operation Herof.

The 18-minute video was released by the BLA just weeks after one of the deadliest attacks in Balochistan, a region that has been grappling with a separatist insurgency by the ethnic Baloch people since the early 2000s. On 26 August 2024, the Majeed Brigade, the elite suicide unit of the BLA, orchestrated a series of simultaneous attacks across different parts of the province. They included a Fedayee (self-sacrificing) attack on a paramilitary base in the Bela district, near Karachi, also involving a female suicide bomber. In one of the deadliest aspects of the operation, more than 20 Punjabi passengers were pulled out from buses on a highway, identified, and summarily executed. Alongside these attacks, police stations were set ablaze, a railway track was sabotaged, and mineral-laden trucks were torched. This coordinated wave of violence, dubbed Operation Herof (translated roughly from Balochi as ‘Black Storm’), was the largest of its kind in terms of scope and intensity since the full-blown separatist insurgency intensified in Balochistan following the assassination of Nawab Akbar Bugti in a military operation, a key tribal and political leader, on 26 August 2006. By choosing the 18th anniversary of Bugti’s assassination, this militant attack was full of political symbolism, besides demonstrating the growing capabilities of Baloch militant groups and the enduring strength of the separatist movement, even after nearly two decades.

The region of Balochistan – which spans from Iran to Afghanistan and Pakistan – is currently going through an intensified and violent separatist insurgency. Economic deprivation, political marginalisation, inequitable distribution of benefits from development projects, and state repression have fuelled a cycle of violence and counter-violence between the state and Baloch ethnic militant groups. The volatile security situation in Balochistan is further complicated by the presence of sectarian and religiously motivated militant groups, adding another source of instability in the region. In recent years, violence has seen a resurgence in Balochistan. In 2019, Balochistan was the worst-affected province, with 263 casualties—accounting for over 40% of the country’s total terrorist-related deaths despite being the least populated province. In 2022, Balochistan, alongside the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK), accounted for more than 90% of militant attacks across Pakistan. In the first quarter of 2024, prior to the latest attack, Balochistan experienced 41% of all terrorist fatalities in the country.

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a significant component of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), has further exacerbated these tensions, straining relations between the ethnic Baloch and the state of Pakistan. Concerns over the fair distribution of its benefits and fears of demographic shifts have deepened mistrust. The government, on the other hand, has accused militant groups of receiving foreign support to undermine CPEC and its vision for regional connectivity.

Militancy and Digital Narrative

Baloch separatist groups, particularly the BLA, have relied on modern information and communication technologies, especially social media platforms, to project their militant prowess, justify their use of violence, attract recruits, and challenge state narratives. A closer examination of the BLA’s propaganda content during Operation Herof reveals significant themes and trends that underscore these efforts.

The themes encompass a spectrum of issues, including the moral justification for violence, recruitment appeals, exploitation of the province’s resources, and state repression, among others. One message emphasises that Baloch people have historically been part of wars for other nations, such as in Oman, but the time has come to fight for their own homeland, insisting that no one from the outside will come to fight for Balochistan. In another video, a former Frontier Corps member, a paramilitary force responsible for counter-insurgency operations in Balochistan, shares his motivation for joining the separatist movement. He explains that during his three years in service, he witnessed firsthand the repression and hatred these forces harboured toward the Baloch people.

Figure 2: Tayyab Baloch, the individual seated in the centre of the photo, is a former official of the Frontier Corps, a military organisation involved in counter-insurgency operations in Balochistan.

The BLA consistently highlights issues of oppression and exploitation, particularly focusing on the Pakistan-China Economic Corridor (CPEC), a multi-billion energy and infrastructure project. It is portrayed as a move to plunder Balochistan’s resources and further suppress their rights and has been invoked to justify multiple attacks against Chinese citizens and its Karachi consulate.

Sacrifice is a recurring theme in these videos. Baloch fighters refer to the sacrifices of their comrades as one of their motivations for joining the freedom struggle and carrying out Fedayee attacks. They also invoke the crackdown on Baloch women and female political activists, emphasising the brutality of state repression. Some militant fighters make direct appeals to their childhood friends, urging them to become part of the struggle, saying that real comradeship lies within the ranks of the liberation movement.

Figure 3: Two childhood friends who became members of BLA’s Majeed Brigade encourage their peers to join the movement and fight for an independent Balochistan.

The pre-recorded video of Mahal Baloch, the third female Baloch suicide bomber, reflects several key themes. It emphasises the necessity of resorting to violence in confronting state oppression, a common narrative among Baloch insurgent groups. Her chosen alias, Zilan Kurd, references a young Kurdish suicide bomber, signalling the Baloch militants’ inspiration from other separatist movements. Zilan Kurd carried out a suicide attack in 1996 targeting Turkish soldiers during a flag-raising ceremony in Dersim province. In the video, Mahal speaks in Balochi, Brahvi, and Urdu to resonate with a diverse audience and maximise her reach. She also pays tribute to Shari Baloch, the first Baloch female suicide bomber, further reinforcing the group’s evolving narrative on the role of women in militant activities. Moreover, she frames her actions as part of a broader struggle for both national liberation and gender equality.

Figure 4: Screenshot from the prerecorded video of Mahal Baloch, a female suicide bomber from the BLA’s Majeed Brigade involved in Operation Herof.

Information technology has fundamentally changed the dynamics of how reporting is done and how information about militant groups is understood in significant ways. First, it has considerably diluted the reliance by militant groups on traditional media and its role as an intermediary to disseminate their messages/propaganda. Violent groups like the BLA now use platforms such as Telegram and Rumble, where they project their attacks and disseminate their literature and content independently. Social media apps and digital platforms grant militant entities a significant psychological advantage by allowing them to continuously share real-time updates about ongoing attacks. The continuous flow of information as the attacks unfold enhances their ability to shape the narrative and sway public perceptions.

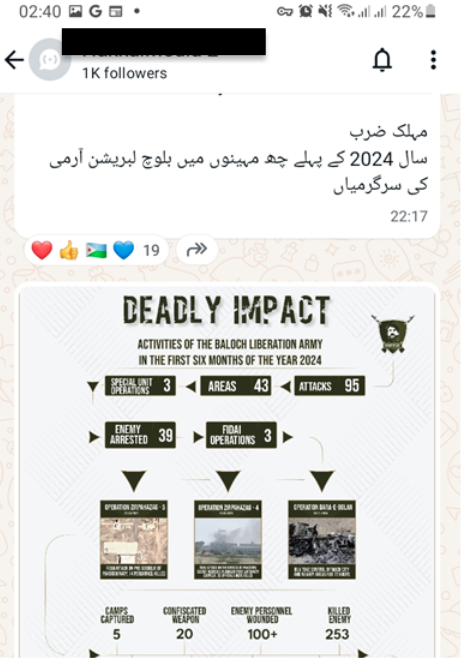

Besides this, information technology has enabled militant groups to sustain public interest in their activities over extended periods. By releasing videos, audio, images, and biographical sketches of attackers over weeks or months, they keep the conversation alive across platforms. The information they share on Telegram or Rumble is then disseminated in more mainstream social media and messaging apps like X and WhatsApp.

Figure 5: BLA’s statements and videos on Telegram and Rumble are quickly disseminated on mainstream media platforms, including X.

Figure 6: The BLA also operates a WhatsApp channel to disseminate its propaganda.

Conclusion

The increasing sophistication of BLA’s use of social media and messaging platforms in recent years to project and amplify its cause has made the Pakistani state’s counter-insurgency efforts more difficult. Despite being banned on most social media platforms, the BLA has been able to disseminate its propaganda through social media apps like Telegram and WhatsApp. The group’s media channel serves as a primary source for the BLA to share its content. The effectiveness of the bans are further compromised when BLA’s videos, audio, and other content appear on mainstream platforms like X, shared by their sympathisers, journalists, and researchers. This cross-platform dissemination challenges both tech companies and the Pakistani government as they contend with the persistent sharing and easy accessibility of militant discourse despite attempts to restrict it.

Figure 7: The BLA shares most of its videos, audio, battle images, and statements on its official Telegram account,.

The Baloch separatist insurgency, a low-simmering threat compared to the religious militancy and transnational dangers posed by groups like the Islamic State, has managed to leverage its relative obscurity to exploit modern information communication technologies. The linguistic aspect adds another layer of difficulty, as over 90% of BLA propaganda is in regional languages like Urdu, Balochi, and Brahvi. This creates a significant challenge for tech companies, which often lack the resources and personnel familiar with the cultural and linguistic dynamics of the region.

To tackle this challenge, tech companies should make efforts to identify extremist content on social media in languages commonly used by separatist groups. It is also essential to increase the number of content moderators well-versed in these languages to effectively counter militant propaganda and enable more research into the working dynamics of these groups.

A coordinated effort among tech companies is essential to effectively tackle the issue of cross-platform information sharing by militant groups. Additionally, the Pakistani government must be vigilant and adopt a dynamic policy that adapts to the evolving nature of threats posed by militant groups. Recent police investigations have revealed that militant groups in Swat Valley in northern Pakistan have used PUBG chat rooms for communication to evade electronic surveillance. While enhancing vigilance to deny militant groups a platform is crucial, it is equally important to ensure that such measures do not lead to further suppression of dissenting voices.

This concern is particularly pressing in Pakistan, where access to X has been restricted and inaccessible for months without a Virtual Private Network (VPN), and there has been a general trend of internet slowdowns without government explanation. In Balochistan, where internet blackouts are common, digital spaces—especially X—serve as an important tool for non-violent activists advocating for the recovery of missing persons and holding the state accountable for human rights violations.

The state’s challenge lies in navigating the need to stem militant groups’ propaganda flow while ensuring people’s rights to access information. Most importantly, a comprehensive response to militant groups’ use of technology should be integrated into a broader counter-insurgency strategy. This strategy must address tactical issues, such as the instrumentalisation of modern communication by non-state actors, while also tackling the strategic challenges rooted in the social and political dynamics behind the separatist insurgency in Balochistan.

Sajid Aziz is an independent researcher whose work revolves around security and foreign policy issues. He has previously worked as a Consultant at the Strategic Policy Planning Cell (SPPC), an Islamabad-based research think tank.