Introduction

Memes are an integral part of modern-day communication. In their ubiquity, memes are consistently co-opted by extremist actors, including the far right, for which memes are a standard part of their online propaganda and mobilisation repertoire. Memes reflect not only a general trend towards increasingly audiovisualised communication but also that extremist messages are often presented in a supposedly harmless, humourous, and apolitical guise.

Memes play with ambivalence and evoke associations in their recipients. In this way, they are able to place their messages on the borderline between humour, schadenfreude, and bigotry, between the unbearable and the permissible. They flood the internet and spread in a flash. It is difficult to track them for deeper scrutiny as they continuously evolve, which poses significant challenges to researchers.

On the one hand, quantitative research is sporadic and tends to use computational clustering methods to cover broad areas but remain content-wise at a superficial level. On the other hand, qualitative studies go into depth but rely on an arbitrarily defined set of examples that do not allow for the abstraction of findings.

Trying to bridge this methodological lacuna, we applied a mixed-methods approach to scrutinise the usage of hateful and discriminatory memes in German-speaking extremist scenes. In particular, we analysed which social groups are particularly targeted by memes and which visual elements, rhetoric, argumentation, and aesthetics are used to communicate group-related hate.

This Insight summarises key findings of a study published in the online magazine, Machine Against the Rage. In this study, we scrutinise the role of meme-based communication in the far-right Telegram sphere, focussing on the prevalence of five different hate categories. Based on a large dataset, we show which characteristics of argumentative motives, aesthetic styles and rhetoric can be analysed and how different groups of actors make use of hate memes.

Approaching Telegram’s Hate Memes

Our analysis focused on a dataset of 8.5 million images posted by 1,675 far-right, conspiratorial, and esoteric German-speaking Telegram channels monitored by the Federal Association against Online Hate since 2021. In Germany, Telegram became a central pillar for mobilising and organising anti-government protests, particularly during the early years of the COVID-19 pandemic, and a digital hotbed for extremist messaging.

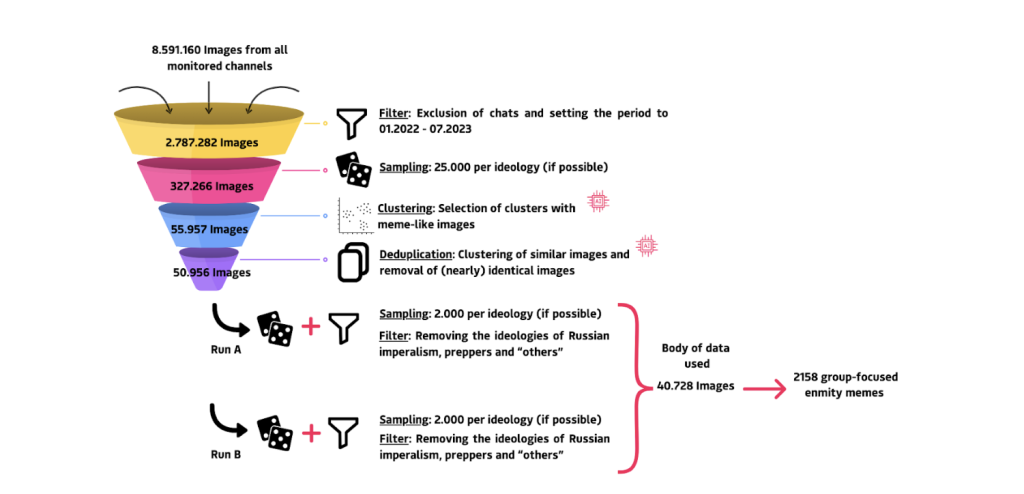

To ensure a broad sample and reduce the impact of pandemic-related content, we narrowed the timeframe from January 2022 to July 2023 and excluded group chat data. Based on their ideological orientation, we categorised the channels into ten different extremist sub milieus spanning from conspiracists and extreme-right groups to neo-Nazis and QAnon believers. From the remaining 2,787,282 images, we randomly selected 25,000 images from each of these ideological subgroups.

Figure 1: Visualisation of the multi-stage sampling process

To increase the chances of selecting visual content containing both text and images, we applied OpenAI’s CLIP model (clip-ViT-B-32), which is designed to interpret both visual and textual content. This automated process filtered the dataset down by 82.8%, ensuring that potentially relevant memes were not inadvertently excluded. From there, we selected a random sample of 2,000 images per sub-milieu. Highly similar images were removed with a deduplication technique using CLIP embeddings and cosine similarity with a strict threshold. This left us with a final dataset of 40,728 images for manual annotation.

The material was analysed using a visual discourse analysis approach. Following Lisa Bogerts, we understand “visual discourse to be a set of visual statements or narratives that structures the way we think about the world and how we act accordingly”. For our analysis, it is particularly important to know what social groups are made visible, how often they are depicted, and how they are represented. Therefore we combined a quantitative content analysis – for example, counting of the visual elements – with the qualitative identification of narrative structures and strategies of persuasion.

We identified 2,158 memes that were likely to be discriminatory, representing 5.30% of the total dataset. These potential hate memes were then annotated by an external team of trained students, who analysed the type of prejudice (such as antisemitism, misogyny, LGBT hostility, hostility toward Muslims, and racism), along with the narrative structure, rhetorical style, visual elements, and overall aesthetic of each meme. All categories were carefully developed from the dataset and adapted to each specific type of hate.

The Frequency of Hate Memes

When analysing a representative sample, most hate memes (31%) can be read or interpreted as misogynistic. There were also significant levels of racist references and LGBT hostility, each present in 28% of the images. Antisemitic content made up 18% of the hate memes analysed, while hostility towards Muslims was the smallest category at 6%. Notably, 9% of the memes showed intersections of several hate categories. Our findings highlight the frequent overlap between misogyny and LGBT hostility, as well as between racism and hostility towards Muslims.

Figure 2: Relative frequency of hate categories https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/19367877/

A more detailed picture emerges when looking at which ideological actors discriminate against which marginalised social groups. The channels of QAnon supporters are particularly noteworthy. Within these channels, almost one in three (32%) hate memes can be interpreted as antisemitic. Hate memes from these channels account for 19% of all antisemitic memes in the dataset. Similarly, in esoteric channels, 39% of hate memes can be interpreted as racist, accounting for 18% of all racist memes in the dataset. In right-wing populist contexts, almost half (49%) of the hate memes used here can be classified as misogynistic.

Elements of Visual Misogyny

Most misogynistic memes draw on common gender stereotypes between men and women (21%), while 17.7% depict women as sexual objects. Intriguingly, even without explicit nudity, memes can degrade women as sex objects. For example, when beautiful women are over-sexualised, and women’s bodies that deviate from the normative beauty standards are devalued. Another salient category portrayed women as stupid (16.2%), subordinating to male dominance. Although these often subtle forms of degradation dominate the data set, we also identified explicit forms of misogyny. For example, 5.5% of misogynistic memes trivialise (physical) violence against women, and 6% deny their self-determination.

A comparative analysis of the annotated image elements reveals that gender stereotypes between men and women play a central role in these depictions. Unsurprisingly, women (199 instances) are the most frequently represented, followed by men (112 instances), in the misogyny category. The portrayal of women as sexual objects can also be seen in the image elements. Nudity appears frequently, with 65 images annotated as such in this category. However, nudity has a strong presence not only in the category itself, but also in comparison to other hate categories: 6.5% of all misogynistic memes feature nudity, while in the case of LGBT hate, nudity appears in only 3.5% of all memes in this category.

Figure 3: Network visualisation of image elements and hate category https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/19357862/

More unexpectedly, politicians from German-speaking countries also feature prominently in misogynistic memes. In fact, with 8.6%, this image element appears even more often than nudity. A qualitative review shows that many of these depictions involve female politicians, particularly from the Green Party, often portrayed as hysterical, simple-minded, or incompetent. Their physical appearance is also frequently targeted. While one might question whether attacking (female) politicians is inherently misogynistic, the pattern is telling: male politicians tend to be associated with different attributes, while women seem to trigger a particular kind of hate.

Measuring Meme Virality

Moving away from the concrete composition of visual content, we were interested in measuring if (and which) hate memes go viral on Telegram. Two hierarchical regression models were calculated to test the hypothesis that the use of hate memes increases the reach of posts. Although the manual method only covered a relatively small segment of the entire monitoring system, we ensured that the sampling approach allowed for an abstraction of the sample. A second random sample of 6,474 messages from the 322 channels that also published memes was created and used as a reference dataset, resulting in a total dataset of 8,632 messages. The first regression model (first row of Figure 4) shows that the independent variable meme/no meme has almost no effect on sharing between channels. The second regression model (below the first row of Figure 4) shows that hate categories as an independent variable have only a small effect on sharing. Specifically, misogynistic memes are shared less on average, while antisemitic memes are shared more than memes in other hate categories.

Figure 4: Negative binomial regression on the influence of meme type on the number of shares Influence of two regression models on the reach of a meme https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/19367923/

At first glance, these results seem counterfactual: While we have seen that women are particularly targeted by memetic hate communication, the results of the calculated regression models indicate that misogynistic memes spread less in the analysed Telegram channels than memes of other hate categories. One possible explanation is that these memes are so ubiquitous and familiar that there is little incentive to forward such messages. On the contrary, antisemitic memes are forwarded more often than other hate memes, even though they are much less present in the dataset overall. Antisemitism is particularly rumour-driven, spreading not through direct experience but through hearsay – what no one knows, what no one has seen, but what people tell each other: promising conditions for a viral meme.

Conclusion

Telegram is not particularly renowned as a platform for memetic creativity. This is also partly due to the fact that Telegram’s public communication is strongly orientated towards one-to-many communication. As well, messages are not sorted algorithmically, so visual content is not favoured over text-only content as on other mainstream platforms. Instead, Telegram users make eclectic use of other sources, such as the image board 4Chan, which suggests a more strategic and less organic meme production.

The Telegram memes we analysed demonstrate that the visual language is less oriented towards digital subcultures and more towards chauvinistic everyday humour. The visual language works strongly with ambivalences and associations, which makes it difficult to clearly recognise right-wing extremist agitations. As the memes are based on current events, our findings only offer insights into one episode of memetic communication on a specific platform. A similar snapshot of other platforms would presumably be different. Telegram – with its chronologically ordered feed – facilitates massive posting behaviour that encourages the DIY mentality that is inherent to participatory forms of image production. This makes it difficult for practitioners to identify hotbeds of extremist communication on this specific platform. In addition, platforms require a level of sensitivity that is difficult to achieve through automated content moderation. Particularly in the context of antisemitism, special investment should be made in raising awareness of codes and symbols.

—

This article is based on a research study for the German Federal Association for Countering Online Hate led by Lisa Bogerts, Wyn Brodersen, Christian Donner, Maik Fielitz, Holger Marcks and Pablo Jost. It was published in the online journal Machine Against the Rage, no. 5 (German only): https://machine-vs-rage.bag-gegen-hass.net/five-shades-of-hate/