Introduction

On 26 April 2024, Fursan al-Tarjuma, an umbrella organisation of pro-Islamic State (IS) media outlets that publishes IS content worldwide, announced the addition of the At-Tamkin Malay Media Foundation under its umbrella. Similar to other foundations under the Fursan al-Tarjuma banner, At-Tamkin Malay likely serves as a hub for the translation and dissemination of IS-related media content, focusing on both official content producers such as Amaq News Agency and IS’ weekly newsletter, An-Naba, as well as on content produced by unofficial pro-IS supporters (known as the Isdaraat Al-Ansar, or simply Ansar).

At-Tamkin Malay’s inclusion in Fursan al-Tarjuma suggests its integration into a broader online ecosystem, leveraging Fursan al-Tarjuma connections to extend its reach into platforms, websites, and spaces such as the I’lam Foundation and Raud. This inclusion also indicates that, like all foundations under Fursan al-Tarjuma, At-Tamkin Malay is likely subject to a certain degree of standardisation and control within its activities. The extent of this integration and standardisation will be explored further in this Insight.

Fig. 1: Announcement shared in official Fursan al-Tarjuma channels announcing the addition of the At-Tamkin Malay Media Foundation.

At-Tamkin Malay branded content was produced and disseminated between April 2024 and June 2024. During this time, most of the content produced was focused on translation work, with only two posters produced by Ansar designers having received At-Tamkin Malay branding. No new content or posts in its official channels have been published since early June. In terms of timing, this appears to coincide with a number of IS-related incidents within the Malaysian threat landscape, most notably the May 2024 Ulu Tiram attack and a subsequent spate of arrests focused on pro-IS supporters. However, no official announcement has been issued by either At-Tamkin Malay or Fursan al-Tarjuma regarding this cessation (temporary or otherwise) of activities.

This Insight explores At-Tamkin Malay’s formation, activities, and subsequent cessation within the context of the Malaysian extremist Islamist threat landscape. Given the lack of concrete publicly available information regarding recent events in Malaysia, it should be noted that this Insight does not provide concrete claims as to the reasons behind At-Tamkin Malay’s cessation of activity. Instead, this Insight seeks to provide a threat assessment of outfits such as At-Tamkin Malay within the local context and what the formation and legitimisation of a Bahasa Melayu-focused foundation mean in the context of Fursan al-Tarjuma’s – as well as wider IS global media jihad – strategy.

Background: Past IS-Related Media Outlets in Malaysia

From a historical perspective, At-Tamkin Malay Media Foundation is the third major IS-legitimised outfit to involve content specifically targeting Bahasa Melayu (or Malay) speakers. The first was the well-known Katibah Nusantara Lid Daulah Islamiyah, a military unit established in 2014 consisting of foreign fighters hailing from Southeast Asia. Katibah Nusantara’s content remains the regional gold standard in terms of quality and outreach.

Second was the Malay-language Al-Fatihin newspaper launched in June 2016 in the Southern Philippines. It similarly focused on content connecting Southeast Asian foreign fighters in the Middle East with their home region. While Al-Fatihin was marketed as a Malay-language publication, it nevertheless produced a significant amount of content tailored for Bahasa Indonesia speakers, where IS enjoyed a larger support base.

Following the failure of the 2017 Marawi Siege, there was a noticeable decline in both the quality and frequency of SEA-focused content produced by central IS outfits in the Middle East, leading to a “digital vacuum” in IS propaganda across Southeast Asia. Among the remaining active outfits in the region, the At-Tamkin Indonesia outfit is most notable, producing and disseminating Bahasa Indonesian content under the Fursan al-Tarjuma umbrella. Like most Fursan al-Tarjuma foundations, At-Tamkin Indonesia mainly focuses on translation work, occasionally lending its branding to content produced by Ansar groups. The outfit remains highly active and widely circulated in the region, particularly on encrypted messaging platforms such as RocketChat, TamTam, and Telegram.

Fig. 2: Poster shared in Fursan al-Tarjuma official channels indicating Tamkin Indonesia as part of its official umbrella.

Fig. 3: Poster shared in At-Tamkin Indonesia official channels, allegedly produced by Ansar designers and subsequently branded with the At-Tamkin Indonesia logo.

Another noteworthy development was the brief formation of the “self-styled” Al Malaka Media Centre in Malaysia, which was not recognised by any major IS-related media arms such as Fursan al-Tarjuma, or IS Central media bureaus. The nature of the Al Malaka Media Centre is contested amongst experts; this Insight aligns with the conclusion drawn by some experts that the analysis surrounding the outfit was subject to misinformation and was ultimately alarmist.

Establishment of At-Tamkin Malay: Content & Online Activity

The 26 April announcement by Fursan al-Tarjuma stated that it was announcing the addition, rather than the formation, of At-Tamkin Malay Media Centre. However, there is no evidence to suggest that At-Tamkin Malay existed prior to the 26 April announcement.

Fig. 4: Both versions of the At-Tamkin Malay Media Foundation logo, appended to content published under its official channels

At-Tamkin Malay’s online activity has largely been focused on two platforms: an official RocketChat channel and an official Telegram channel—the latter of which required verification by a Telegram bot prior to entry. Both channels were regularly active following their creation on 26 April 2024. Activity on the RocketChat channel ceased on 11 May 2024, after 56 posts, while the Telegram channel remained active until 9 June 2024, concluding with 142 posts.

Of the 142 known posts across both channels, the majority were translations of updates and photo reports from the Amaq News Agency, a pattern common to all Fursan al-Tarjuma media foundations. Intriguingly, content analysis by native Bahasa Melayu speakers identified that most of these translations were machine-translated, with errors suggesting they were produced by non-native Malay-speaking content creators. This is consistent with findings by Munira Mustaffa on the translation work conducted by the aforementioned Al-Malaka Media Centre, which indicated a possibility of a “non-native Malay speaker … attempting to produce Malay language content”. Similarly, it is possible, although unconfirmed, that the translators behind At-Tamkin Malay were not native Malay speakers.

Only two of these posts contained content produced by Ansar designers. Notably, the text within both these posters does not exhibit the hallmarks of machine translation and is likely written by native Malay speakers.

The first was a poster published on 6 May 2024, which issued threats against disbelievers and apostates for their actions in various regions that are linked to groups involved in the 2017 Marawi Siege in the Philippines.

Fig. 6: Poster attributed to Ansar designer published in At-Tamkin Malay channels on 6 May 2024.

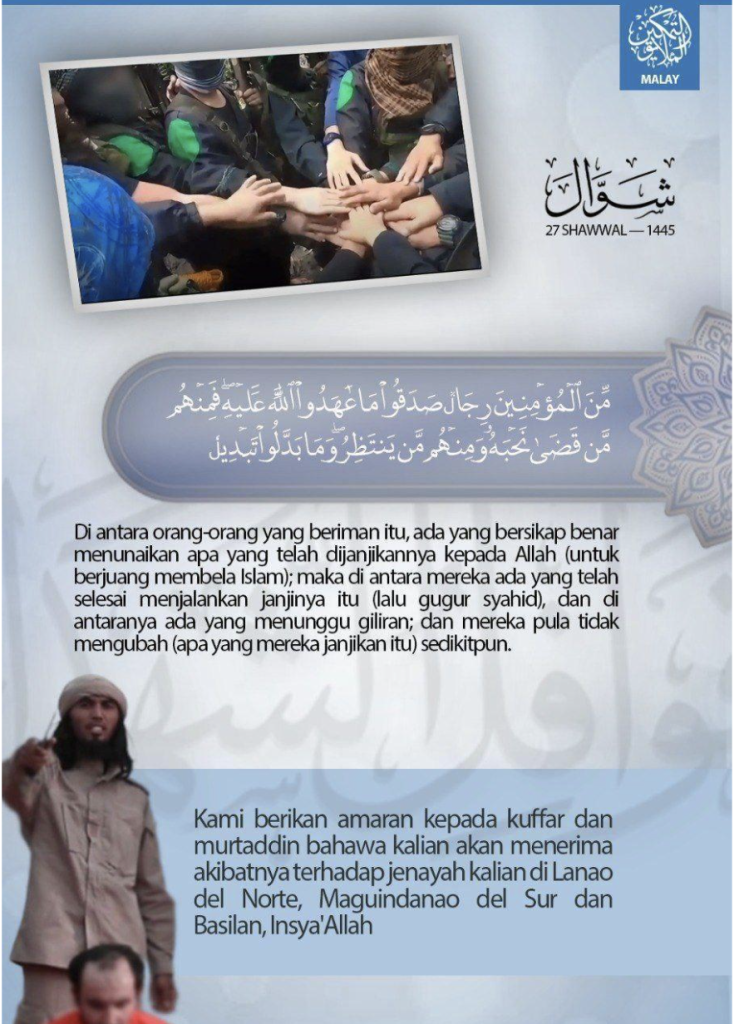

The second was also a poster, published on 24 May 2024, which featured images of Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim and US President Joe Biden with their faces crossed out. The accompanying text condemned democracy as a system of taghut (disbelieving rebels) and warned that any attempt to transform the Shari’ah was an act of shirk (polytheism). The message was attributed to “Your brother from Tamkin Melayu”.

Fig. 6: Poster attributed to Ansar designer published in At-Tamkin Malay channels on May 24, 2024.

Recent Threat in Malaysia: Correlation, not Causation

Neither the Ulu Tiram attack nor the arrests of pro-IS suspects in June have any concrete links to At-Tamkin Malay Media Foundation, and no evidence suggests that the content produced by At-Tamkin Malay played a role in inspiring the Ulu Tiram attack or the activities of the arrested IS supporters. Furthermore, there has been no official statement from Malaysian authorities or by Fursan al-Tarjuma confirming that any of the individuals arrested were involved with At-Tamkin Malay or consuming its content.

Nevertheless, the timing of these incidents and the cessation of At-Tamkin Malay activities suggest a few possibilities based on the available information. First, it is possible that the administrators involved in At-Tamkin Malay were among those arrested, leading to the abrupt end of its activities. According to Malaysian authorities, the arrests of pro-IS individuals on 21 and 22 June following the Ulu Tiram attack in Malaysia revealed threats against several prominent political figures in the country, including Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim. This aligns with the content of at least one of the posters produced under At-Tamkin Malay (Fig. 6). Secondly, the recent intensified focus on IS within the Malaysian counterterrorism landscape may have discouraged At-Tamkin Malay from engaging in overt activity for the time being. The foundation appears to be keeping a low profile during this period of heightened surveillance and arrests.

Evaluation: Wider Strategic Shift in Fursan al-Tarjuma

While much of the current analysis regarding the status of At-Tamkin Malay remains speculative, further insights can also be drawn concerning the wider strategy of Fursan al-Tarjuma. The 26 April announcement from Fursan al-Tarjuma specifically highlighted that the addition of At-Tamkin Malay Media Foundation was part of its ongoing commitment to being “the singular source for translations of the Islamic State official media.” This suggests that Fursan al-Tarjuma seeks not only to provide widespread content translation but also to centralise the currently decentralised global efforts in such translation work.

In the broader context of IS’ global media jihad campaign, the formation of At-Tamkin Malaysia and the shift towards centralisation within Fursan al-Tarjuma’s strategy indicates a recognition by IS’ online media apparatus of the need to reintegrate the decentralised elements that emerged in the vacuum following IS’s post-2017 withdrawal from the region. As previously underscored by experts, the relationship between the global IS online media apparatus, and local pro-IS content producers (Ansar) is likely symbiotic. The Ansar provides content and insights into local and regional grievances, enhancing the effectiveness of the content produced. In return, the global apparatus offers legitimacy and broader outreach through its connections to the wider ecosystem and recognition by the central IS media structure.

While At-Tamkin Malay Media Foundation only produced two pieces of content that could be directly attributed to local Ansar designers, these efforts indicate a desire to incorporate local content producers into the ecosystem. At the same time, this selectiveness in what content is legitimised by the broader outfit points to a trend of re-centralisation within the global IS media jihad. This intent to exert control over the current decentralised ecosystem is also evident in announcements from Fursan al-Tarjuma and its affiliates, denouncing certain unaffiliated media channels as unofficial, non-representative of IS narratives, or fake channels set up by state actors’ intelligence services.

Fig. 7: Posts in official Fursan al-Tarjuma channels highlighting other online IS-related media outlets as either fake or non-representative of IS.

Conclusions and Implications

Careful consideration is required in how we approach the formation of outfits like At-Tamkin Malay. Misinterpretations or weak evaluations can lead to alarmist conclusions. For instance, the assertion by some that At-Tamkin Malay’s dissemination of drone-related guides within its channels indicated a specific intent to instruct on building makeshift weapons, such as explosive drones, could be considered alarmist. A deeper examination of the ecosystem within the context of Fursan al-Tarjuma norms suggests that sharing these guides was simply part of a wider translation effort, a practice common across most foundations under Fursan al-Tarjuma’s umbrella. Therefore, this did not necessarily reflect a specific localised intent by At-Tamkin Malay to encourage drone attacks, but rather a wider objective within the global media jihad ecosystem. Failing to recognise such nuances risks diverting already constrained counterterrorism resources toward countering unfounded or unsubstantiated threat assessments.

Fig. 8: The drone attack guides published by across IS-related online media channels, which have been translated into multiple languages and disseminated in multiple regions.

These developments allow us to identify broader trends that remain actionable for both practitioners and policymakers within the tech industry. The examination of At-Tamkin Malay content and activities highlights the ease with which such foundations can be established, specifically with the increasing availability of machine-translation capabilities and the continued presence of platforms hosting pro-IS communities such as RocketChat. The use of an official logo tied to the global media jihad, as seen in At-Tamkin Malaysia’s content, carries implications beyond mere brand recognition. Rather, it suggests an increasing re-centralisation of the global media jihad online ecosystem – how this re-centralisation will play out in different countries and regions is highly dependent upon the respective contexts.

Nonetheless, the underlying symbiotic relationship between the periphery and the centre of the IS global media jihad persists: the former provides content, context, and outreach for the latter, while the latter confers legitimacy on the former. In this environment, practitioners and policymakers must adjust their understanding of how to prioritise ‘official’ and ‘unofficial’ IS-related content and actors. The means of content production within the current ecosystem is increasingly controlled by Ansar groups, necessitating a strategic shift in how we target and address content creation. Our approach must recognise and adapt to this evolving dynamic. Simultaneously, official outlets should not be neglected, as they continue to provide structure and legitimacy. They are not defunct, rather, their roles within the ecosystem have changed. Targeting one without addressing the other would only result in partial mitigation of the overall challenge faced in the region.