Introduction

Following the 29 July 2024 knife attack in Southport, England, which left three children dead and ten others injured, riots rocked the UK as far-right agitators took to the streets to protest against the presence of migrants, particularly those from predominantly Islamic countries, in the UK. Within just hours after the attack, far-right accounts on social media platforms such as X began spreading misinformation, in which they falsely alleged that the perpetrator was a Muslim migrant who had recently arrived in the UK. While authorities later clarified that the perpetrator, identified as 17-year-old Axel Muganwa Rudakubana, was a UK citizen born in Cardiff to Rwandan parents — whom neighbours described as being “heavily involved with the local church” — far-right accounts nonetheless continued to purvey misinformation intent on aligning the event to fit their broader anti-migrant narrative.

While the proliferation of misinformation immediately in the aftermath of a horrific tragedy is problematic enough, of even greater concern is that far-right accounts have actively promoted harmful conspiracy theories purporting that, for instance, the UK government and United Nations (UN) orchestrated counterprotests from Muslims in the UK to generate widespread violence that would, in turn, instigate a civil war (discussed at length below). Such a situation, certain far-right accounts maintain, would engender a crisis enabling government authorities to curtail UK citizens’ civil liberties, thus playing off a common conspiracy theory that a “global elite” — ostensibly comprised of the Transatlantic political, financial, military, and intelligence communities — endeavours to subjugate the general public. Accordingly, this Insight investigates how far-right accounts on X have used the 29 July Southport attack as a springboard to proliferate disinformation narratives and concludes with some recommendations on how tech companies might counter these actions.

Who-Dun-It? How Online Misinformation Sparked Real-World Violence

The mistaken identity of the perpetrator of the Southport knife attack directly gave rise to riots on 30 July that resulted in 39 police officers being injured after far-right agitators hurled bricks and bottles at law enforcement personnel while setting police vehicles ablaze. Speculation over the perpetrators’ identity originated from a news outlet called Channel3Now, which, according to The Guardian, potentially uses AI to generate US and UK news content. In a report dating from 29 July, Channel3Now misidentified the perpetrator as Ali Al-Shakati, alleging that he was an asylum seeker who had recently arrived in the UK by boat in 2023.

Fig. 1. A post from an X user with over 400,000 followers alleging — incorrectly — that the perpetrator was a Muslim immigrant named Ali Al-Shakati.

Posts by X users proliferating this misinformation garnered an extensive audience reach. As of 8 August 2024, the above post (see Fig. 1) alleging that the perpetrator was a Muslim immigrant reached 6.8 million views, while the original poster’s subsequent reply featuring the misidentification along with the added — false — details that the perpetrator had arrived by boat to the UK reached 1.4 million views.

Fig. 2. A post from an X user featuring an altered news headline.

Such posts also featured blatant attempts by some X users to mislead viewers into believing that certain content — which was factually incorrect — was being reported by authoritative news outlets. The above post (see Fig. 2), for instance, evinces such deception, in that the headline appears to imitate the display style of The Guardian by using its characteristic serif font against a red background. The difference in font (serif versus sans-serif) and variations in the shade of background colour, however, clearly reveal that “17-year-old Ali Al-Shakati” is an altered addition to the original headline.

From Misinformation to Disinformation: The Proliferation of Conspiracy Theories

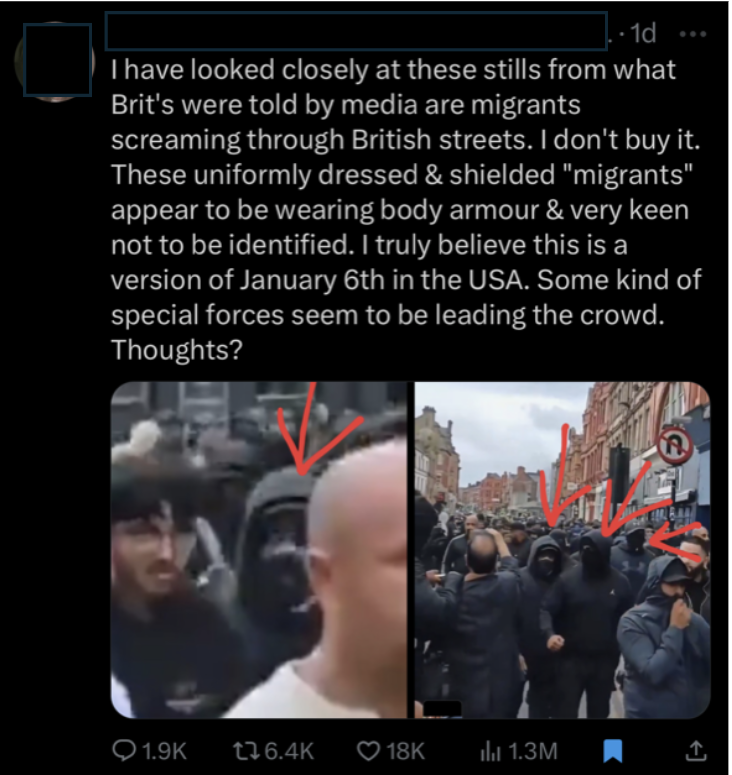

Stemming from misinformation surrounding the identity of the perpetrator and disingenuous efforts to mislead viewers about the authority of news sources, some far-right X accounts began promoting a conspiracy theory that counterprotests were organised by UN or UK officials in order to instigate some sort of alleged false-flag event. One X user with over 223,000 followers opined — without offering any definitive evidence — that counter-protestors were wearing body armour and were engaging in behaviour similar to that of agitators who stormed the US Capitol on 6 January 2021 (see Fig. 3). Notably, Jan 6 is another event that a staggering number of people — both far-right agitators and regular citizens alike — have claimed to be a false-flag operation conducted by US intelligence agency personnel rather than supporters of former US president Donald Trump. This same user further alleged in another post — which received over 1.3 million views — that persons who appear to be Muslim migrants in the UK are, in fact, UN soldiers “housed in Hotels as Guests of the Crown,” and that the counterprotests are “an Operation to garner UK Public Support for Digital Identity so Britons can ‘feel safe’.”

Fig. 3. A post from a far-right X account alleging that counter-protestors were engaged in some sort of organised false-flag operation; the post garnered approximately 1.3 million views.

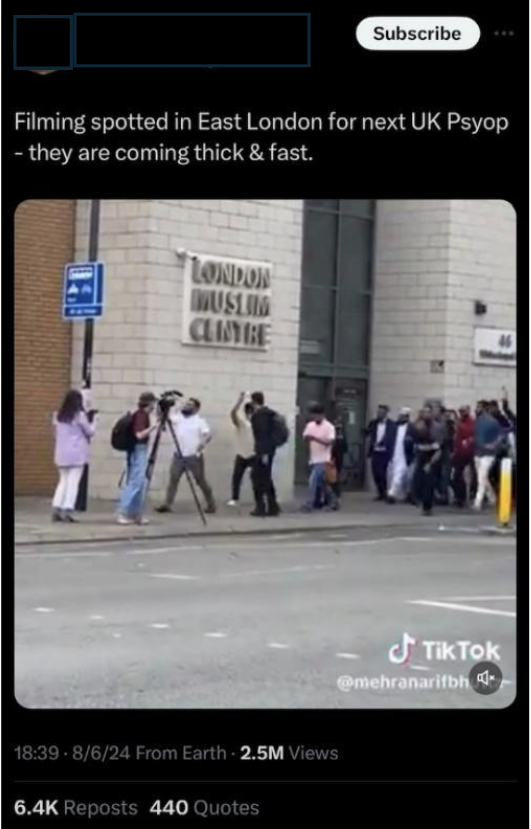

In a similar vein, another X account with over 517,000 followers posted a TikTok video showing counter-protestors chanting and walking past a person recording from a tripod-mounted camera, which this X user alleged was filming for “the next UK Psyop” (see Fig. 4). In a different post by a far-right X account with over 417,000 followers, another TikTok video shows a woman claiming that the counter-protestors — assumed to be illegal immigrants without any substantiating evidence — are “soldiers hired by the British government to slaughter Britons” and that “the Globalists are planning a civil war in the UK” (see Fig. 5). A fourth far-right X account with over 235,000 followers added in a post — which garnered over 1.8 million views — that “globalists” had supplied counter-protestors with a cache of guns in preparation for “[a]n armed uprising by extremist Muslims” and that “the Globalists are planning a civil war in the UK.” Such discourse calls to mind the conspiracy theory promoted by white nationalists known as the Great Replacement Theory, which falsely alleges that “globalists” seek to use migrants to instigate widespread violence for the purpose of committing genocide against white persons.

Fig. 4. A post from an X account alleging that counterprotests were staged as part of a psyop; this post received over 2.5 million views.

Fig. 5. A post falsely alleging that counter-protestors are illegal immigrants hired by the British government to instigate civil war.

Taking Countermeasures

Speculating about the hidden motives of certain organisations might not be illegal, but conspiracy theories like these still threaten the stability of democracies in many ways. Racist postulations about the alleged Great Replacement Theory exacerbate social tensions, while the proliferation of altered and misleading news content degrades public trust in media. The spread of disinformation purporting that national governments and international organisations seek to instigate civil war erodes public trust in those institutions and inhibits them from operating effectively.

Combating such discourse on X is further complicated by the fact that Elon Musk, the platform’s owner, has engaged in spreading disinformation relating to the Southport knife attack and subsequent riots. Musk had, for instance, replied to a video of rioters in Liverpool saying that “civil war is inevitable” and later shared — though quickly deleted — a fake Telegraph article that alleged UK PM Keir Starmer was considering sending far-right protestors who had been arrested to “emergency detainment camps” in the Falklands given that the UK’s prison facilities had recently neared their maximum capacity.

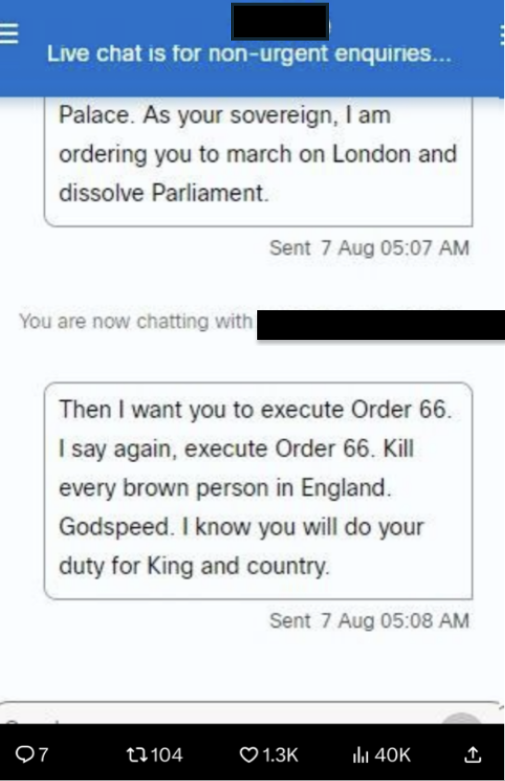

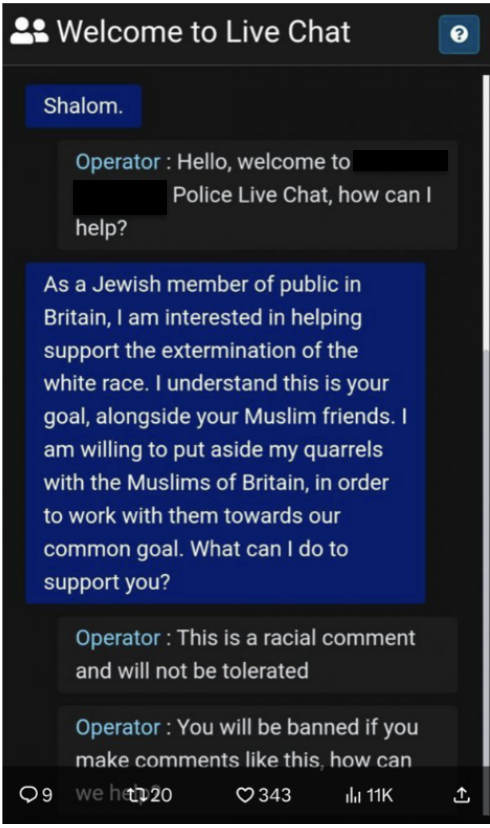

Additionally, some law enforcement measures have been abused by far-right trolls. For instance, trolls have used 4chan’s /pol/ (politically incorrect) boards and X to circulate examples of their harassment of live chat features run by some UK police departments that allow users to report crimes — enacted to improve public access to law enforcement — in an effort to promote and encourage such inappropriate behaviour (see Figs. 6 and 7).

Fig. 6. A far-right troll harasses a police live chat feature, asking the law enforcement officer to “execute Order 66” against persons of colour in England; Order 66 is a reference to the Star Wars movie Revenge of the Sith, in which the enactment of this order results in Republic soldiers betraying and executing their generals, leading to the overthrow of the democratic Republic and the creation of the authoritarian Empire.

Fig. 7. In another police live chat, another far-right troll appears to pose as a Jewish Briton and makes antisemitic and racist statements.

In response to the plethora of violent behaviour and virulent online discourse stemming from far-right accounts, Keir Starmer announced that anyone participating in violence during protests would “face the full force of the law,” and UK police have consequently arrested over 400 persons in relation to the riots, some of whom may be subject to prosecution under counterterrorism laws. Meanwhile, Mayor of London Sadiq Khan, one of the UK’s most senior Muslim public officials, called for amendments to be added to the Online Safety Act passed in October 2023 by Parliament in an effort to better counter the sort of widespread online discourse that resulted in real-world violence.

These are appropriate steps to take, especially in cases when online discourse explicitly calls for violence. Prosecuting persons who violate such laws ensures that the consequences for engaging in such behaviour are made readily clear to those who might consider partaking in similar actions in the future, thus serving as a deterrent. Additional countermeasures, however, might stand to bolster online security. In the case of police live chat features designed for non-emergency purposes only, law enforcement agencies might consider partnering with tech companies to develop and train AI programs capable of identifying, screening, and bookmarking comments from trolls, whose harassment wastes law enforcement officers’ valuable time.

With respect to the moderation of content on social media platforms such as conspiracy theories, while their promotion may not constitute the violation of any law, problematic content can nonetheless be countered to some extent through the use of labelling, as with community notes on X. This, however, requires that social media users take the initiative to correct such information on their own initiative — and that they do in fact provide verifiable, correct notes. Moreover, labelling content is further complicated by the fact that it requires considerable resources relative to the ease with which disinformation and misinformation can be posted.

Social media companies might consider developing machine learning algorithms to fact-check and post community notes, with transparency at the forefront. However, the challenge lies in creating consistently reliable AI for these tasks, which is highly resource-intensive. Moreover, errors on the part of such algorithms risk undermining public trust in these technologies and platforms. Nevertheless, social media and tech companies would benefit from engaging in dialogue over ways to leverage novel technologies to provide guardrails for managing online discourse. At the very least, such algorithms might alert social media analysts to trending content that appears to contain calls for violence in order to enable analysts to identify and investigate such content themselves.

Any countermeasures, however, ultimately rest on the institutional and political will to counter the spread of disinformation, particularly when it instigates real-world violence. In this respect, tech companies and governments must liaise and seek out solutions that might better stem the proliferation of malign online behaviour.

Mason W. Krusch is an independent researcher specializing in hybrid threats and information operations. His work has previously been published in Small Wars & Insurgencies (Taylor & Francis), Global Network on Extremism & Technology (GNET), and The Defence Horizon Journal (European Military Press Association). His research interests include unconventional warfare, Eurasian security, and far-right extremism and online radicalisation. He holds a MS in Global Studies and International Relations from Northeastern University (Boston, MA) and a BA in History from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.