Introduction

In recent years in Argentina and Brazil, far-right governments have risen to power, represented by the leadership of Argentinian economist Javier Milei and the former Brazilian military officer and President Jair Bolsonaro. The political movements led by these political actors have largely used social media to expand their messages in the public sphere. This Insight will discuss the role of social media in creating and expanding narratives to consolidate far-right movements in Argentina and Brazil.

It can be argued that the ascent of these political movements was influenced by the tactics of then-US President Donald Trump under the advice and playbook of Steve Bannon. Bannon, who led the alt-right news platform, Breitbart, promoted conspiracy theories as part of his public agenda and intentionally fomented polarisation in the political scene based on his idea that “if you want to change politics, you have to change culture”. This model was adopted in Argentina and Brazil by similarly nationalistic, alt-right, conspiratorial actors. The changes in the online media ecosystem in these countries helped usher in the expansion of values and ideas that, in the past, were restricted in their circulation in the mainstream. The rise of the far-right in these major South American countries amplified and proliferated – with the help of mainstream news editors – extremist views that perhaps had lay relatively dormant until new leadership mainstreamed such ideas.

Furthermore, in both countries, far-right influencers exploited economic, security and social crises to promote conspiracy theories that blamed a ‘leftist enemy’ for the situations at hand.

The role of far-right influencers

Over the last years on social media, far-right influencers have expressed views that have legitimated extremist positions in the mainstream. Sometimes, by showing scenes of their daily life on TikTok or Instagram, they are able to cultivate a following along similar ideological lines as their audience. This creates a link with their followers that ends with the spread or adoption of far-right ideas by youth. Furthermore, influencers are able to exert pressure on far-right movements in their countries to radicalise and move further towards the extreme right. Promoting conspiracy theories and misinformation increases the number of views they receive; they are thus rewarded through payments on social media. I use the concept of “micro political entrepreneurs” to understand this phenomenon.

Although far-right influencers are not considered as important as the leaders of a country’s far-right movement, they serve an important role in the circulation and propagation of ideas, creating legitimacy for extremist views. This is crucial for the sustainability of a political process in contemporary society.

Argentina’s Pandemic and the Far Right: Javier Milei’s Path to Presidency

During the pandemic, influencers that used to occupy marginal roles in Argentina garnered an increased following on social media. These influencers expressed and amplified an alternative and right-wing view during the pandemic. Together, they created a so-called resistance program on YouTube with the name of the “Hate Ministries”. This occurred during a period when the state suspended freedom to circulate in public spaces to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Through social media, they echoed a speech defending “freedom” against the State that used to be in line with more libertarian ideas of the economist Javier Milei. Furthermore, they participated in political meetings at the foundation of his party, La Libertad Avanza, until they distanced themselves or were expelled by the elite circle that dominated the party. Ultimately, they were important figures in the movement to construct a climate where Milei’s ideas resonated in the public sphere.

In that context of restrictions, young people started to see those influencers – linked to Milei’s party, La Libertad Avanza – as leaders of a new youth movement to fight and resist state restrictions in support of freedom. At the same time, the traditional right, represented by the leadership of Mauricio Macri and Patricia Bullrich, began to establish links with far-right leaders, such as Milei. Initially, they used Milei to legitimise their efforts to shift the public agenda to the right. This strategy succeeded, but ultimately Milei ended up undermining the traditional right and consolidating support for that ideological spectrum himself.

Milei expressed his extremist views on mainstream and social media, directing his polarising viewpoints to combat what he called the “political caste” of “corrupt politicians” and “socialists” that – in his view – ruined the country. In this language, Milei associates the “political caste” with left militants, public servants, and progressive intellectuals but never with conservatism or political rights. He established a dichotomy between “good Argentines” and “thieves”. This is a similar tactic established by Trump and Bolsonaro with their polarising rhetoric.

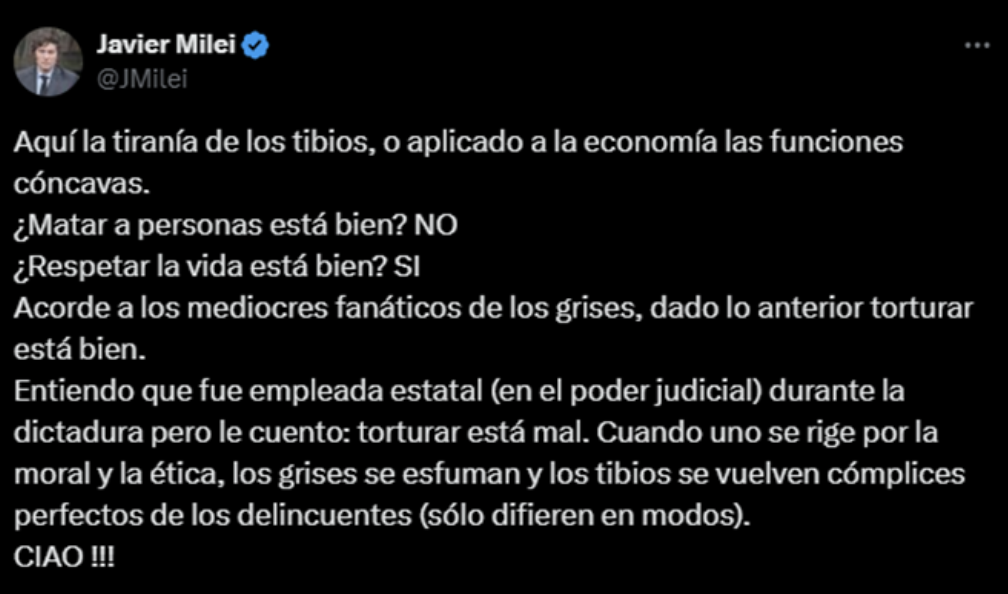

Milei uses X to communicate his government actions and, most importantly, to attack his critics. These range from journalists and celebrities to anyone who disagrees with his policies. In addition, he uses X to promote conspiracy theories formulated by far-right influencers. Argentine far-right influencers linked to the Milei administration, such as “Gordo Dan”, said that since the purchase of X by Elon Musk, restrictions for their speech on social media disappeared, so they attribute in part Milei’s victory to Musk.

Milei attacking a centrist politician, Elisa Carrió, on X, formerly Twitter

Since Milei’s victory, Agustin Laje, a far-right influencer who has been excluded from mainstream media due to his vindication of military dictatorship and promotion of conspiracy theories, has appeared on Todo Noticias (TN), a mainstream TV channel. This represents a process of naturalization of the far right in mainstream media.

On social media, Milei’s followers have been promoting politics of repression against drug traffickers, endorsing what can be defined as “bukelismo”, the adoption of a regime similar to Nayib Bukele in El Salvador, taking photos of drug traffickers in jail without human rights contemplations. In the polarised vision expressed by Fernando Cerimedo, one of Milei’s advisors, those who don’t support this politics of hard repression are allied to drug traffickers.

Brazil and Bolsonarismo

Olavo de Carvalho (1947-2022) was an astrologist and philosophy professor linked to the resurgence of far-right conservatism in Brazil. During the center-left Workers Party (PT) administrations of Lula (2003-2010) and Dilma Rousseff (2011-2016), Carvalho denounced that Brazil was transformed into a “communist” country and moved to Virginia, where he defended Trump’s policies and values.

Carvalho’s influence in promoting extremist views on social media from Virginia played an important role during Bolsonaro’s administration (2018-2022). But Carvalho was also influential in the larger and relevant bureaucracy during the administration, using his influence over Bolsonaro’s sons (who were previously his students) and the president’s Foreign Policy Advisor, Filipe Martins. The ambassador of Brazil to the United States during this period, Nelson Foster, was designated, considering his close relationship with Olavo’s ideas. Ernesto Araújo, the first Foreign Policy Minister of Bolsonaro’s administration, also gained that position due to nepotism.

Carvalho was one of the first to teach online courses for groups and promote his right-wing ideas on Orkut, a Brazilian version of Facebook, used mostly in the country at the beginning of the century. Bolsonaro paid tribute to Carvalho in a famous speech at the Brazilian embassy in Washington in 2019, where he said: “Brazil is not an open ground where we intend to build things for our people. What we have to do is deconstruct a lot. Undo a lot. So that later we can start doing. If I can serve so that, at least, I can be a turning point, I am already very happy”. Steve Bannon was also present at that event. As previously delineated, Bannon was one of the first, through Breitbart News, to use social media to promote extremist views in the political arena.

During the 2018 elections in Brazil, WhatsApp allowed political content to be sent on the platform without restrictions on the number of users who receive it. Bolsonaro’s campaign advisors, under Bannon’s advice on how to manipulate public opinion through social media, used WhatsApp to send and proliferate conspiracies that the candidate of the centre-left of the Workers Party (PT), Fernando Haddad, wanted to “sexualize kids”. The rate of those who intended to vote in 2018 for Bolsonaro and who shared political content via WhatsApp was double that of Fernando Haddad’s supporters (40% versus 22%, respectively). That massive campaign of WhatsApp messages was also supported by businessmen allied to Bolsonaro. After the 2018 elections in Brazil, WhatsApp limited the number of people who could receive one message simultaneously, probably with the intention of correcting the kind of manipulation allowed in 2018.

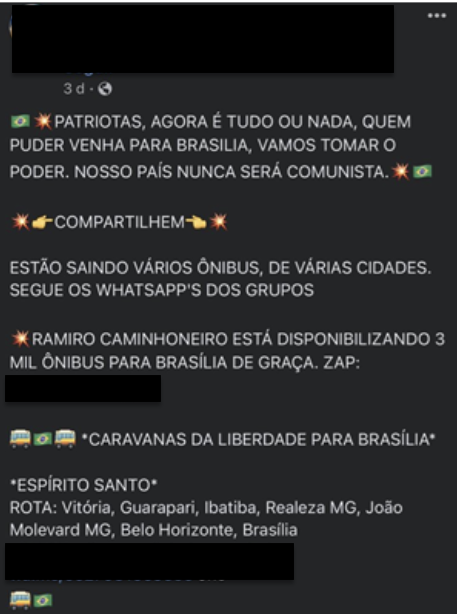

Social media was also a large factor in Brazil’s January 2023 attempted coup. Extremist protesters and agitators called for a demonstration in the capital of Brasilia via Telegram and WhatsApp under the code “Festa da Selma.” This, quite similar to the Jan. 6 insurrection in DC, represented an extraordinary attack on the country’s democratic institutions. This occurred following allegations of fraud in the 2022 elections, supported by President Bolsonaro and the military, which were amplified on social media.

Telegram groups exhibited violent language mixed with anti-communism and attacks on the Supreme Court Minister, Alexandre de Moraes. Such language promoted the idea of a civil war against the State and conspiracy theories that ended with the attack in Brasilia. Fernando Cerimedo, owner of the site La derecha diario, participated in the Brazilian attempted coup and afterwards used that knowledge for Milei’s campaign on social media.

Content circulating on Telegram extremist groups in Brazil in January 2023 calling for military intervention

Content circulating on Telegram extremist groups in Brazil in January 2023 calling for a military coup

Content on Facebook calling for a military coup against “communism”

Conclusion

It is important to recognise the international links between far-right actors and parties. The influence of the US case in Argentina and Brazil cannot be overstated.

The recent episode related to Elon Musk and its conflict with the Brazilian Supreme Court shows how the bolsonarista far-right used the situation to present him as a “liberty icon”. Bolsonaro and his followers presented Musk and his social media company (X) as an ultimate representation of freedom of speech. As well, that situation allowed far-right deputies from bolsonarismo to travel to the US and Europe to denounce that in Brazil exists a “left-wing Judiciary dictatorship” that restricts freedom of expression. Furthermore, Milei has positioned himself on the international stage as a liberty icon for the far right, “king of freedom” in his messianic terms, promoting conspiracy theories in worldwide forums as Davos and being supported by Musk.

In Argentina, the pandemic was important because it empowered far-right influencers under the state’s denunciation of freedom restrictions. But in Brazil, under Bolsonaro’s corrupt and complicated administration, the pandemic limited the government’s approval. In any case, far-right influencers have grown in both contexts through conspiracy theories aiding radicalisation; it is from here that they profit like a business.

The debate over the regulation of social media is complicated, but it is necessary to recognise that the far-right uses the idea of “freedom of expression” outlined in the US Constitution to justify their violent language calling for civil war and anti-democratic demonstrations as we have seen in the US and Brazil.

Further regulation of the extremist content of social media would be useful to prevent this process of proliferating radicalising materials and propaganda. There must be a balance between freedom of expression and the preservation of democratic institutions that are being attacked by far-right movements on social media and the public sphere. In particular, it is important to regulate extremist and disinformation content on X; since Musk’s takeover of the platform, it has become a space particularly relevant for the proliferation of such content. Some equilibrium has to be established between the profit interests of the social media corporations and the democratic principles and institutions that are essential to our societies.