Introduction

On 14 February, Indonesia will host the world’s largest single-day elections as nearly 205 million voters and 250,000 candidates compete for around 20,000 positions. These will be the fifth direct presidential election and sixth legislative elections since the fall of the deceased dictator Suharto and his 32-year New Order regime in 1998.

Indonesian politics in the post-Suharto democratic era have become increasingly polarised. This has been exacerbated by the state, which, under current President Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo, has cracked down on critics, influenced institutions, strengthened control, and pushed controversial laws, including attempting to delay the elections.

In this context, officials are concerned about the spread of disinformation; a 2023 survey found that 42.3% of respondents believed some disinformation regarding the elections, such as the existence of electoral interference from authorities and foreigners, for instance. There are also concerns about the spread of narratives and propaganda from terrorist groups around the elections, which seek to discredit the elections and the democratic process and potentially motivate attacks. This Insight examines how disinformation and extremist content polarise the political environment, fuelling social tensions and threatening Indonesia’s regressing democracy.

The Indonesian Electoral Landscape

The three candidates running for the presidential election are Prabowo Subianto, Ganjar Pranowo, and Anies Baswedan. Prabowo, Suharto’s former son-in-law, was an ex-special forces commander and general who was dismissed from the military after various allegations of grave human rights violations. He has run for elections twice, in 2014 and 2019, both bitterly losing to incumbent President Jokowi, who appointed him the defence minister in 2019.

Ganjar Pranowo, the two-time former governor of Central Java (the second-largest province in terms of electorate), represents one of the country’s largest political parties, the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle. The party is led by Megawati, the daughter of Indonesia’s first leader, Sukarno (who was deposed by Suharto in 1965). She is part of Indonesia’s oligarchic political elite, as is Prabowo. Anies Baswedan is running as an independent and was Jakarta’s former governor, who came to power following a controversial election. He is also backed by established parties.

Prabowo has been polling the highest, largely due to Jokowi’s support for his candidacy in this election. A controversial court ruling that allowed Jokowi’s son to run as Prabowo’s vice-presidential candidate has not only raised concerns about Indonesia’s democracy but also about Jokowi’s ambitions to build his own political dynasty. Jokowi is one of Indonesia’s most popular leaders, partly because he comes from a non-political and military elite background. However, Ganjar and Anies have been catching up to Prabowo, and there is a growing possibility of a run-off election in June.

The Ahok Episode: How Hardline Groups Weaponised Disinformation

In May 2017, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, otherwise known as Ahok, was sentenced to jail for blasphemy a month after losing the Jakarta Governor elections to Anies Baswedan, the current presidential contender. Ahok, a Christian of ethnic Chinese origin, was Jakarta’s incumbent governor, and close to Jokowi. A video of him quoting a Quranic verse which warned against allying with Christians at a campaign stop went viral across social media in September 2016. The video was cut and edited to make it seem that he had insulted the Quran by a university lecturer who has since been jailed and released for editing the video to incite hatred.

The video sparked widespread anger, and hardline socio-political Islamist groups, like the extremist Islamic Defenders Front (FPI), galvanised public sentiment and held mass protests in Jakarta, some of which turned violent. They launched smear campaigns against Ahok, demanded his arrest and conviction attacked his ethnicity and religion. Indonesia has a history of violence perpetrated by ‘native’ mainly Muslim Indonesians against Christian, ethnically Chinese Indonesians. They also voiced support for Anies, claiming that he would help defend Islam, and made his electoral approval rating surge. They essentially transformed the election from being centred around Jakarta to ‘defending’ the majority religion in Indonesia.

A similar event occurred in the 2019 presidential elections when FPI and related groups backed Prabowo against Jokowi. Jokowi picked a prominent Islamic cleric as his vice-presidential candidate to strengthen his religious credentials. Since 2014, he (himself a Muslim) has been constantly maligned over perceptions he is anti-Islamic, that he is an ethnic Chinese or has links to China.

In the current digital landscape surrounding the 2024 elections, mis- and disinformation proliferate across online platforms, perpetuated by diverse groups and entities seeking to advance their agendas.

Terrorist Election Interference

Monitoring efforts by the National Counterterrorism Agency (BNPT) reveal the dissemination of propaganda by groups such as the Islamic State-linked Jamaah Ansharut Daulah (JAD) and the former Al-Qaeda affiliate Jemaah Islamiyah (JI). Although the general threat of terror organisations has significantly diminished over the last two decades, these two groups give reason for concern, particularly during election periods. In October 2023, Indonesia’s counter-terrorism unit arrested 59 terrorists across the country: 40 were JAD members, and 19 were JI members.

JAD views elections and the democratic process as ‘taghut’, or against (their interpretation of) Islam. Some of the arrested JAD suspects were allegedly stockpiling weapons and bomb-making materials and planned to attack police stations (amongst other potential targets) during the elections. During the 2019 elections, security forces announced they had foiled a plot by a JAD member to target the General Election Commission in Jakarta. So, although JAD has been in an organisational and operational decline since the late 2010s, there is a threat of potential attacks from some of its elements in the coming weeks. The symbolism of a successful attack around a key election could motivate hardline JAD cells into action, reinvigorate some support, and ideologically strengthen their narratives against democracy. It will also signal organisational resilience, despite significant gains in counter-terrorism efforts, and would be celebrated by Islamic State supporters.

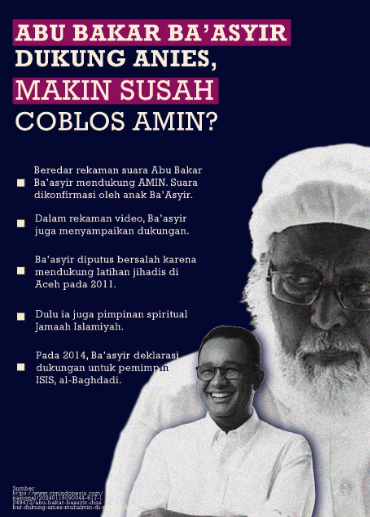

The threat from JI is different from JAD. JI has morphed into a quasi-political and social organisation, adopting a subtler approach by infiltrating civil institutions and attempting to mainstream its extremist narratives and undermine democracy under the guise of social and political activism and engagement. The BNPT last year disclosed that they had identified members of a terrorist group in a party registered for the general elections; the unnamed party was later barred. These were likely JI members, some of whom have attempted to create their own party in the past. There has also been disinformation targeting Anies in this regard. Notably, the endorsement of Anies Baswedan by a former JI leader and Islamist scholar, Abu Bakar Ba’asyir, is being used to circulate false narratives that voting for Anies results in a victory for JI (Fig. 1). Anies has not been able to shake off perceptions that he is a hardline Islamist since 2017, suffering significant reputational damage after he aligned with Islamists to demonise his Christian rival.

Fig. 1: Image circulating on social media linking Anies and Abu Bakar

Growing Anti-Refugee Stance

Recently, ethnic and economic tensions in Indonesia have been fuelled by the arrival of Rohingya refugees in Aceh, Sumatra. In December 2023, a group of students raided a refugee centre in Banda Aceh, harassing and forcibly evicting the families who sheltered there. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) said that the attack was motivated by a coordinated and orchestrated anti-immigration online disinformation campaign. 91% of comments on four Rohingya-related posts on the UN’s official X account in November were deemed hate comments. UNHCR’s representative stated that “professionally made” content with similar messages against them, the UN, and Rohingya was proliferating across multiple online platforms via bot accounts.

On social media in Indonesia, false narratives are spreading about alleged Rohingya criminality and how the refugees intend to occupy Indonesian land and create colonial settlements like Israel. While it remains unclear who is behind these campaigns, they have demonstrated the significant influence of disinformation in aggravating tensions and motivating violent actions. It is interesting to note that the campaigns have spread across borders; in India, right-wing disinformation networks are using the issue to promote their own anti-immigrant campaigns against Rohingya refugees there. In Indonesia, the disinformation has changed public sentiment against the Rohingya, who were previously welcomed in Aceh. Although negative sentiments were slowly over economic concerns, the sudden violent flare-up in the pre-election period indicates a potential political motivation behind these disinformation campaigns.

Common Election Smear Campaigns

Another sensitive issue taken advantage of is a long-standing, underlying anti-Chinese sentiment amongst certain segments of the Indonesian population. Thousands of ethnic Chinese Indonesians have been killed over perceptions they are communist, against Islam, against Indonesia, and other falsehoods. Discrimination became entrenched during Suharto’s tenure. According to a 2022 poll, over half the population believes that Chinese Indonesians wield too much influence over the economy and politics, and over half believe that Chinese Indonesians, who have been living in Indonesia for hundreds of years, are loyal to Beijing and not Jakarta.

Anti-Chinese sentiments are continually politicised and exploited during elections, with misinformation surrounding China’s involvement in Indonesian affairs contributing to xenophobic rhetoric and anti-Chinese conspiracy theories. Last August, a fake video claiming that a Chinese businessman was printing counterfeit money to buy electoral votes went viral. Other hoaxes alleged that Chinese citizens could vote in Indonesia’s elections and that presidential candidate Ganjar was funded by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Yet another video claimed that President Jokowi’s mother was a CCP agent. A deepfake AI video of President Jokowi speaking fluent Mandarin also spread across social media. President Jokowi’s terms have seen billions of USD in Chinese investment pour across sectors, especially infrastructure. This has exacerbated concerns of sovereignty and nationalism and claims that Jokowi has sold out to economic Chinese interests, especially due to clashes between Chinese and Indonesian workers in the key nickel sector and China’s continued maritime law violations and activity in Indonesian waters.

AI is also transforming political campaigning in the country. AI-generated images of Prabowo and Gibran (President Jokowi’s son) have circulated, depicting them wearing rainbow pins and ties (Fig. 2). The exploitation of the contentious and sensitive topic of LGBTQ+ rights in Indonesia is a common tactic used even by politicians themselves to sway voters against opposing candidates.

In this year’s campaign, Prabowo’s campaign team has used Midjourney to create ‘cute’ cartoons to appeal to a younger electorate who may not be familiar with his darker past (Fig. 3). AI is also being used to track social media sentiment, create chatbots, and target sections of voters. Midjourney has not commented on Prabowo’s campaign, even though its guidelines bar AI from being used in political campaigning. These are just a few examples of the myriad disinformation tactics currently flooding digital platforms ahead of the Indonesian elections. The aforementioned sentiments and issues will be used to smear candidates, add to tensions, and polarise voters.

Fig. 2: AI-generated animated images of Prabowo and Gibran purporting to (controversially) support LGBTQ+ rights

Fig. 3: A still from one of Prabowo’s AI campaign videos

Deeper Challenges and Government Measures to Counter Disinformation

Ahead of the elections, the government has taken steps to counter the harmful impact of political disinformation. The Ministry of Communication and Information has intensified steps to improve digital literacy, ‘cyber patrols’ that report hoaxes and publish information about hoaxes to the public. It is also collaborating with social media companies and fact-checking organisations to ensure the publication of factually robust news content.

Yet, two main factors hinder the government’s attempts to counter political disinformation. The first is a lack of public trust in oligarchic political parties and institutions. In a 2022 poll, only 54% of respondents had moderate trust in parties in the House of Representatives. The fact that President Jokowi is creating his own political dynasty entrenched with corruption and economic woes is compounding this problem.

The other factor is the persistent use of disinformation campaigns by legitimate political actors themselves with various vested interests in politics, government and security. Since at least 2014, these entities have used ‘buzzers’ – professional content creators paid thousands of dollars to produce and disseminate political propaganda – to amplify certain narratives and influence public opinion. Following the mass anti-racism and independence protests in Indonesia’s Papuan provinces in 2019, investigations by Bellingcat and the BBC found that pro-government bots and buzzers were being used to influence national and international opinion in favour of Indonesia and against Papuan independence.

The public’s waning trust in the authorities, including news outlets and journalists, is compounded by the fact the state itself is pushing them towards unofficial yet state-mandated sources of (dis)information. This exposes the electoral process and the state to questions about legitimacy, especially coupled with the democratic backsliding, and distracts the electorate from the issues at hand. This creates an environment where extremism can become more pervasive, even if it is an undercurrent.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Disinformation can act as a catalyst for the propagation and mainstreaming of terrorist, hardline, and extremist propaganda and narratives. A study on the effects of political disinformation on domestic terrorism globally showed that the former stoked the latter through increasing polarisation. In the last decade, Indonesia has experienced a rise in religious conservatism and intolerance, largely fueled by the influence of political Islamists. This trend aligns with the long-term objectives of JI, albeit at a slower pace. Increasing questions about the legitimacy of political actors and the electoral process will also feed into extremist narratives like JAD’s.

Addressing the challenges posed by the spread of political disinformation requires a multifaceted approach involving greater transparency and increased collaboration between tech companies, government agencies, and fact-checking mechanisms to improve digital literacy among young users in particular. Platforms should allocate increased attention and resources to countries like Indonesia, with large, young, digital populations. This will take time and will not be possible ahead of these elections. A positive development in these elections is the fact that candidates for high posts, including the presidential seat, have not openly pushed disinformation to smear others, as compared to previous elections.

Tackling buzzers is more challenging but could be possible in the long term with more coordinated efforts between stakeholders. There has to be stronger transparency and accountability from the state, first and foremost, upon which civil society and political literacy organisations can build. Deepfakes and AI-generated content should be marked as such, possibly through developing algorithms to identify such content rapidly and creating algorithms to monitor similar messaging and bot activity. A deeper look at the top trending hashtags or chatter in a country or region could help identify sensitive issues earlier. Tech companies must be at the forefront of helping Indonesia gain digital literacy and play an important role in Indonesia’s democratic future.