Introduction

In May 2023, the Global Network on Extremism and Technology (GNET) hosted its Third Annual Conference at King’s College London. Featuring presentations by Dr Miron Lakomy and Dr Maciej Bożek (University of Silesia), Dr Elizabeth Pearson (Royal Holloway, University of London/VOX-Pol), Stevie Voogt (Moonshot) and Dr Fazeelat Duran (University of Birmingham), the panel Impact of Extremism Research on Researcher Mental Health brought together three seminal projects examining the relationship between viewing terrorist and violent extremist content (TVEC) and researcher wellbeing, aiming to identify strategies and best practices for harm reduction.

This Insight draws from these projects and panel discussions to shed light on the harms extremism researchers face and the need for improved safeguarding practices. It then suggests next steps and best practices for mitigating personal harm at both the individual and institutional levels.

Understanding the Harms

While the academic field of Critical Terrorism Studies emerged in the early 2000s in the context of the nascent War on Terror, the sub-field of online extremism and terrorism gained prominence in the mid-2010s when violent Islamic State (ISIS) propaganda began circulating online. This area of research raises new challenges for academic pursuits in adhering to strict ethical approval processes for fieldwork. In contrast, for researchers studying online extremism and terrorism, “the Internet is the ‘field’” – a domain which has largely eluded ethical and regulatory oversight.

Although the long-term impact of extremism research remains uncertain due to the field’s novelty, studies are underway to assess the emotional and physiological effects of consistent exposure to TVEC. Dr Lakomy and Dr Bożek’s GNET report, Understanding the Trauma-Related Effects of Terrorist Propaganda on Researchers, seeks to understand the personal experiences of researchers frequently engaging with terrorist content. Their findings, derived from a novel experiment using biofeedback and eye-tracking technology, unequivocally demonstrate that extended exposure to such content may induce secondary trauma among researchers. This underscores an urgent need to implement new standards to protect researcher wellbeing.

Moonshot, a global social enterprise founded in 2015 to reduce online harms, has been working since its inception to build evidence-based practices and processes to protect its own researchers from harm. Through mixed-method research involving interviews and surveys, Moonshot’s collaboration with the University of Birmingham examines the effects of engaging with harmful and extremist content on researchers. The project sheds light on effective existing support mechanisms to directly inform future interventions and investments in extremism research.

Emerging from conversations in the wider field about researcher wellbeing, VOX-Pol’s REASSURE project compiles the experiences of online extremism and terrorism researchers across Europe and North America. The project’s initial phase catalogued the range of harms experienced by terrorism researchers based on interviews conducted as part of the study. It highlights the fundamental lack of “formalised systems of care” or training to protect them, often leaving them reliant on informal support networks and coping mechanisms to mitigate those harms. Examining the impact of identity within this context reveals further complexities in the landscape of extremism research.

The Impact of Identity

The nebulous boundaries of the internet make it a challenging field of study, especially in the age of remote work as the lines between work and home have become increasingly blurred. Monitoring terrorist and violent extremist content (TVEC) involves consistent exposure to graphic and distressing imagery and, for many, frequenting spaces that are built for the express purpose of spreading this content. With that comes a considerable social and emotional cost and the risk of developing secondary or vicarious trauma (VT). VT may manifest as sadness, irritation, fear, headaches, memory loss or problems with sleep and concentration. The REASSURE report acknowledges that VT caused by indirect exposure to violence can, in some cases, result in symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

A key finding of these projects pertains to identity and positionality. How trauma presents itself and is managed can be dependent on the researcher’s identity (age, gender, ethnicity, religion, sexuality) and the nature of the stressor. For instance, if a woman of colour is studying violent, racist and misogynist groups, her proximity to the topic renders her particularly vulnerable to harm or abuse. This harm can be passive, through witnessing violence and narratives that target people with her identity characteristics, or active, if she is identified and targeted by the very people she is researching. Beyond causing personal harm, these risks can also perpetuate institutional power dynamics that suppress marginalised voices. Researchers may self-censor, mask their identities, or decline speaking opportunities without institutional protection that can guarantee their safety, significantly impacting career growth.

A researcher’s age and/or career stage were also identified as influential factors in their risk awareness. The reports revealed that older or more experienced researchers were less inclined to report or acknowledge harm than their younger or more inexperienced counterparts. This tendency could stem from a heightened awareness of the risks associated with exposure to TVEC or, conversely, from a gradual desensitisation to violent material over time. While it is encouraging that early-career researchers or practitioners tend to report harm more often, a lack of this same behaviour from more experienced colleagues may also dissuade their younger counterparts from advocating for better institutional safeguards.

Can’t Stand the Heat?

Exploring further implications, the conference discussions delved into the challenges of addressing toxic cultures within research institutions, specifically concerning the treatment of PhD students and early-career researchers. The REASSURE report highlights that younger or early-career researchers often face challenges in voicing concerns within their institutions and are less likely to challenge decisions made by their superiors. Despite experiencing emotional harm in his work, one respondent said: “I don’t want to cause a fuss on my first project. I can do it by myself. That is my thing. I’ll handle it”. This reflects the toxic or ‘macho’ culture that has been found to proliferate within research institutions. The panellists noted a concerning trend of glamourising trauma among extremism researchers (‘How many beheading videos have you watched?’) and the tendency to associate status or success with proximity to violence.

This issue is also compounded by the competitive and volatile job market for entry-level positions. Dr Pearson noted that the immense pressure on young researchers to prove their suitability could prompt risky behaviour or unnecessary exposure to TVEC, driven by a desire to showcase their dedication to the field. The pervasive atmosphere of ‘If you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen’ perpetuates a culture of bullying, especially within academia. It’s important to note that suitability for the job extends beyond personal resilience, and being impacted by distressing imagery does not reflect one’s strength of character.

Changing Cultures

Without institutional support, researchers have been forced to seek help independently and develop their own personal mechanisms to cope with secondary trauma. The projects overwhelmingly concluded that few institutions provide adequate training, care or support for researchers engaging with TVEC regularly. According to Lakomy and Bożek’s report, while 69.4% of respondents strongly agreed that exposure to TVEC should be preceded by training on trauma prevention, only 16.9% of their employing institutions had ever provided mental health support or information on coping strategies.

These findings underscore the need for a fundamental shift in the prevailing mindset, starting at the institutional level. Informed by Moonshot’s longitudinal researcher wellbeing research, Stevie Voogt voiced that transforming work cultures necessitates strong leadership that reframes toxic narratives. Dr Duran suggested that this could start with greater transparency in the recruitment process clarifying role expectations, followed by comprehensive training in the early stages of entry-level positions.

Integrating these changes begins first and foremost, however, with a willingness from leadership, which is not always present. Being a relatively new field, academics and practitioners involved in P/CVE efforts may benefit from borrowing best or ‘inspiring’ practices from other industries and adapting them to best suit the needs of researchers. This would require measurable standards and metrics of change, as well as flexible support tailored to practitioners’ various roles and needs. While shifts in individual mindsets are important, leading organizations must also demonstrate a path towards meaningful change.

To this end, a Working Group focused on researcher and practitioner health and safety has been developed out of the Eradicate Hate Global Summit. The Working Group aims to create a collection of resources and frameworks to help organisations and individuals incorporate inspiring practices towards wellbeing in their work more effectively. In addition, the second phase of the REASSURE project is currently underway, involving active collaboration between law enforcement, journalists, policymakers and tech companies to develop best practices to deal with online harms outside of academia.

Conclusion

Acknowledging and addressing the issues and dynamics described above is essential to fostering a safer, more inclusive, and emotionally supportive research environment. Organisations that have modelled better safety practices, including Moonshot, have stressed that wellbeing cannot be considered an afterthought or a luxury – rather, it must be integrated and prioritised at every stage of work. Here, post-secondary and research institutions have a role in ensuring practitioners have access to resources and measures to support their mental and digital hygiene when engaging with TVEC content.

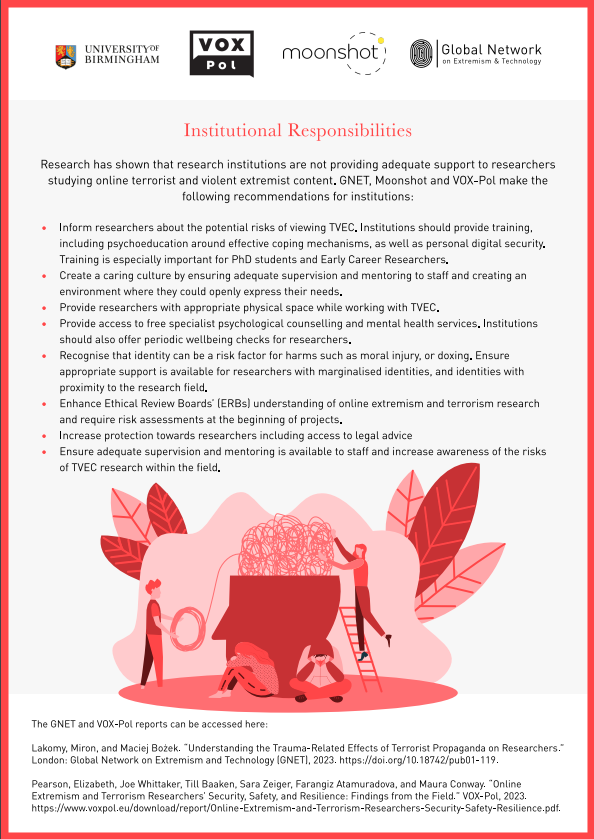

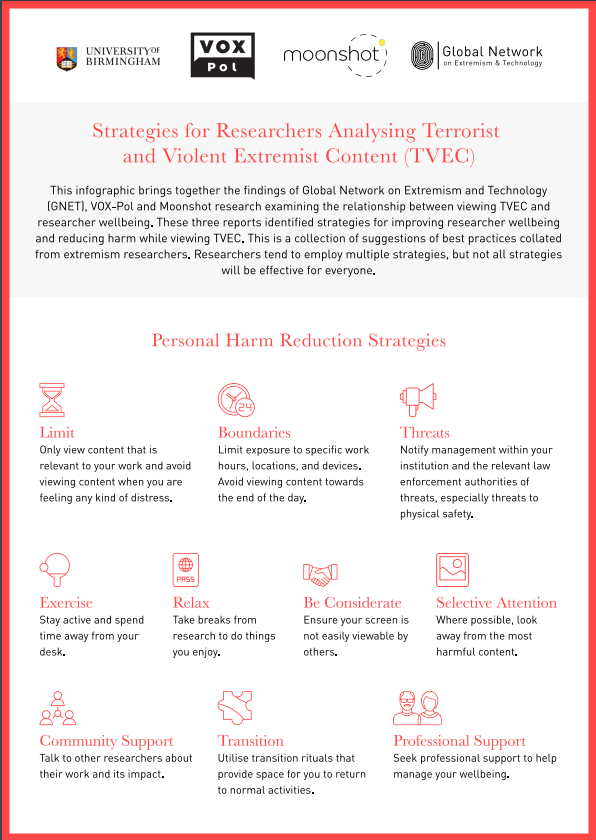

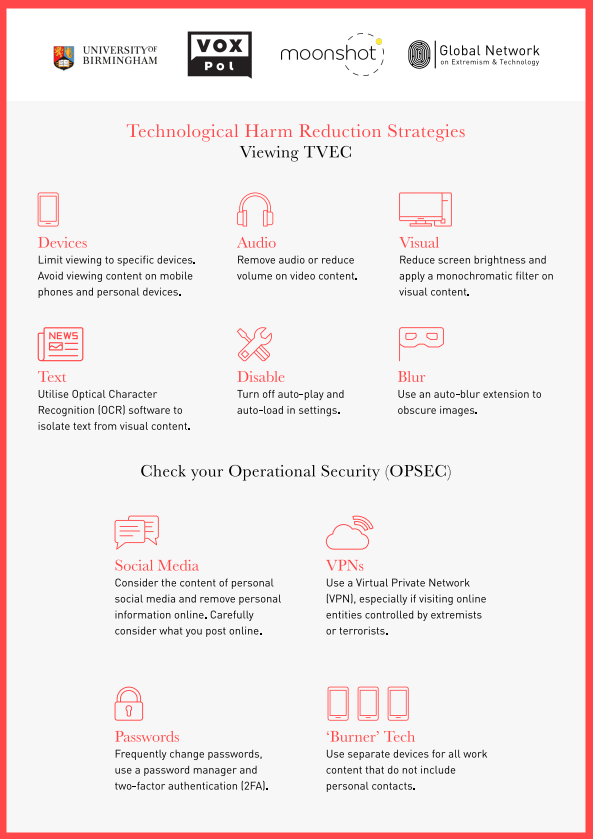

Fig. 1: GNET Infographic suggesting best practices for extremism researcher mental health

Recognising that no one size will fit all regarding practitioner safety strategies is also important. The vast array of identities and other factors that can influence a researcher’s experience with TVEC means that practitioners and institutions must be willing to demonstrate flexibility in the face of unique challenges.

Funding also represents a significant barrier to change, as integrating mental health and digital hygiene support across post-secondary and research institutions comes at a cost. Adopting these recommendations may include restructuring curricula, offering access to mental health professionals, and providing access to technological infrastructure, including burner devices and Virtual Private Networks (VPNs). And while these are costly adjustments, trauma also has an economic impact. Insufficiently addressing these issues can lead to greater staff turnover, more money spent on hiring, and lost productivity due to absenteeism. Further, given the disproportionate impact of TVEC and the surrounding culture on marginalised/early-career researchers and practitioners, failure to integrate a safety-by-design approach risks the loss of innovative and diverse experts engaging in this work. In the long term, integrating appropriate support mechanisms for researchers is likely to be a more cost-effective and sustainable approach to the field.

It is also true that not all good practice costs money. Indeed, community-building was found by all the researchers to be one of the most effective ways to mitigate the psychological impact of exposure to TVEC. The relative nascency of this field may require more intentional efforts to build communities and support networks for practitioner health. Beyond practical measures, broader cultural shifts are also needed to move away from the fetishisation of trauma across the field. As the effects of exposure to TVEC become better understood and more communities of support form, this shift may start to emerge. To enable this, organisations and individuals should be conscious of how toxic work cultures are perpetuated and promote healthier behaviours where possible. By taking these steps at individual and, most importantly, institutional levels, the field of P/CVE can begin to evolve for more sustainable, supportive, and impactful work conditions.

Maddie Cannon is the Project Manager of the Global Network on Extremism and Technology (GNET). Maddie specialises in the far-right, exploring violent extremism in Europe and North America from a gendered and youth-centred perspective using an ethnographic approach.