This Insight is part of GNET’s Gender and Online Violent Extremism series in partnership with Monash Gender, Peace and Security Centre. This series aligns with the UN’s 16 Days of Activism Against Gendered Violence (25 November-10 December).

Introduction

One image shows two young women sparring with each other, donning boxing gloves and athletic wear. A second image shows a young woman wrapping her hands and wrists, presumably preparing for a fight. On her arm is a tattoo of an Othala rune, a symbol common in neo-Nazi and white supremacist communities.

These images, identified in online Active Club spaces, diverge from more traditional portrayals of women in right-wing extremist movements and communities. Instead of quaint cottagecore aesthetics and traditional ‘tradwives’ tending to the family and home, these images present women as activists, ideologues and warriors. While the Active Club network’s portrayals of women still promote traditional gender roles–especially within romantic relationships–the invocation of ‘warrior women’ tropes opens the door to a more palatable form of right-wing extremist activism – one that is less overtly misogynistic and ostensibly more ‘gender equal’.

This Insight serves as a first look into the hypermasculine extremist spaces and communities of the Active Club network and how they co-opt and utilise images of women in their propaganda. We first introduce the Active Club network before reviewing existing literature on representations of women in right-wing extremist content. Next, we identify and discuss distinctly gendered tropes regarding the representation of women and couples in Active Club content. We conclude with a cautionary analysis of how such content can make Active Clubs and similar organisations palatable to women who may view these groups as gender-equal or empowering.

Literature Review

Individual far-right Active Clubs exist as part of a decentralised network of groups that conduct mental and physical combat training while promoting white supremacist, neofascist, and accelerationist ideologies. Active Clubs are primarily active in the US and Canada, consisting mostly of young white men and offering members physical spaces to train and exercise. The group simultaneously advocates for a healthy physique while promoting the Great Replacement conspiracy theory and believes physical violence is the best way to counter their enemies. As Active Clubs increasingly gain mainstream attention, more emphasis has been placed on the network’s hypermasculine characteristics. However, this analysis of Active Club communications shows that women play a significant role in the group’s visual branding and activism.

While right-wing extremists have traditionally venerated (white) women as homemakers, mothers, and sex objects, the Active Club network has begun to portray their women members–at least in their visual propaganda–as fighters and activists akin to their masculine counterparts. In this way, Kathleen Blee’s seminal perspective that women can occupy roles within right-wing extremist groups that extend beyond the familial and social domains withstands the test of time. Moreso standing in as symbols of white heteronormativity as opposed to actual agents of power, women are operatively used—or propagandised—to enhance a group’s image. Eviane Leidig recently underlined a similar phenomenon in which white female influencers advocate for their ‘protection’ due to their inherent vulnerability as women. Simultaneously, these women assert that accepting traditional gender roles under the scope of ‘tradwifery’ enhances their individual agency. Right-wing extremist movements that utilise and invoke this agency while simultaneously offering protection from malevolent forces may therefore be more appealing to women.

Images of women in heterosexual couples may be used to highlight a group’s masculine prowess and appeal to male viewers. According to Alexander Ritzmann, Active Clubs in the US scarcely advertise their inclusion of women, except through images of couples or idealised tradwives. Photos of heterosexual couples suggest the possibility of romantic relationships via membership in the Active Club network, making involvement in such a network an enticing and unique opportunity for both men and women.

While women are most commonly used as a form of marketing in right-wing extremist propaganda, the ways these women are portrayed have shifted from archetypes of weak creatures to athletic sex symbols. Current research does not address how Active Clubs have foregone Madonna-esque depictions of women to instead show them as foils to hypermasculine men or as warriors with more agency than their historical counterparts.

Women in Right-Wing Extremist Activism

We analysed a single Active Club Telegram channel, examining 2,029 images shared between October 2021 and June 2023. Within this collection, 172 images of women were identified – 8.5% of the content within an otherwise hypermasculine space. These images were then reviewed and coded according to a typology created specifically for this dataset.

Fig. 1 (top left), a woman holding a torch at an unknown far-right protest; Fig. 2 (top right), a woman boxing at a gym; Fig. 3 (bottom left), a woman takes a selfie with a copy of Mein Kampf; and Fig. 4 (bottom right), a woman holds a gun at an unknown location.

This typology considered whether the woman in the image was: 1) Engaged in political activism, 2) Visibly part of a heterosexual couple, and 3) Wearing or displaying some form of Active Club branding. The authors then identified and coded these images according to the gendered tropes and narratives they evoke. Over half of the analysed images–53.5%, or 92 out of 172–were of women engaged in a form of right-wing political activism. This included women attending protests (Fig. 1), boxing at the gym (Fig. 2), or posing alongside known right-wing extremist materials (Fig. 3) and guns (Fig. 4).

Portraying women as active participants of the Active Club network provides visual confirmation that there is room for women in these spaces–a point of attraction for female audiences. This portrayal may also attract men who may have otherwise viewed these communities as more male-dominated and who may be interested in the prospect of relationships with like-minded women.

Women in Extremist Branding

In addition to depictions of women as protestors, boxers, ideologues and armed activists, over a third of the photos showing women engaged in right-wing political activism also showed them wearing extremist-branded apparel or otherwise marketing the Active Club brand. Across the entire dataset, these images constituted almost one-fifth (19%) of all images of women.

Fig. 5 (left), an armed woman wears a shirt bearing the Totenkopf, White Power Cross, and the Tyr or ‘warrior’ rune; Fig. 6 (centre), a woman in a Casa Pound club room wears a branded pro-fascist shirt; and Fig. 7 (right) a heterosexual couple wears branded Active Club shirts at church.

Showcasing women as ‘brand ambassadors’ may help advance the Active Club network’s image and reach by expanding and mainstreaming the network’s audience beyond those interested in the network’s typical hypermasculine marketing. Notably, a significant portion (39%) of photos depicting Active Club branding also portrayed a heterosexual couple (see Fig. 7), corroborating the idea that allusions to romantic relationships may be an additional network branding strategy.

Extremist Matchmaking

In addition to a branding strategy, this analysis suggests that the heavy invocation of heterosexual couples in Active Club content may also serve as a mainstreaming strategy. Over a third of the images in our dataset (35%) showed women in apparent heterosexual couples or relationships. Just less than half of these images were of heterosexual couples engaged in otherwise normal, non-extremist activities, as seen in Figs. 8-10, suggesting that these images may be meant for mainstream audiences.

Fig. 8 (left), a couple kissing while ice-skating; Fig. 9 (centre), a couple taking a bathroom selfie, and Fig. 10 (right), a couple at the pool. It is unclear whether these photos show couples that are members of the network or are instead photos taken from elsewhere on the Internet.

However, the remaining plurality of images of heterosexual couples showed them engaged in right-wing extremist political activism or activities, such as stickering (Fig. 11), shaving one’s head to be a skinhead (Fig. 12), or posing with guns (Fig. 13). Notably, in each of the provided instances the woman is more actively involved than her male counterpart.

Fig. 11 (left), a heterosexual couple stickers in a public location; Fig. 12 (centre), a woman shaves a man’s head; and Fig. 13 (right) a woman holds a gun while her male counterpart looks on.

Tropes of Women in Active Club Content

Beyond these three overarching trends, three gendered tropes were identified within Active Club content. These tropes can be broadly categorised as invocations of ‘white beauty’, depictions of ideologically aligned couples and portraying women with agency.

White Beauty and Nazi Eye Candy

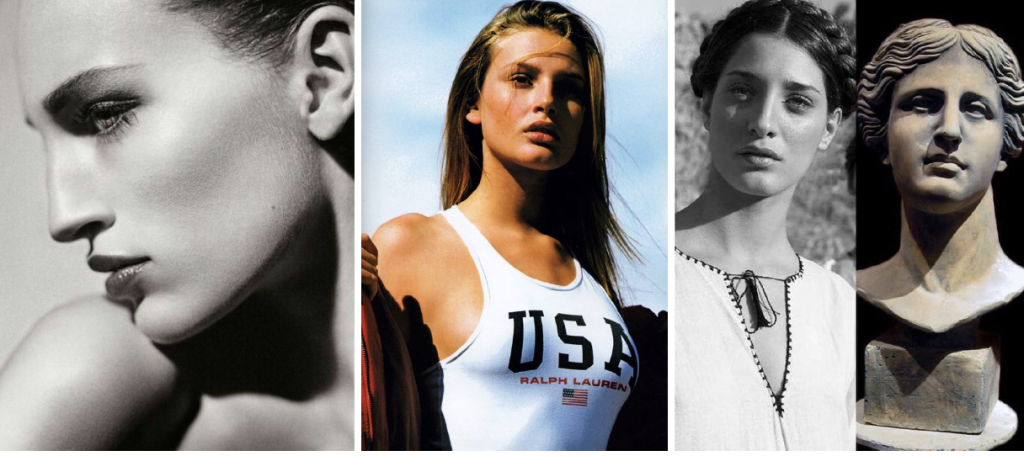

Images highlighting (white) women’s physical beauty and appearance are commonplace in Active Club content. Some images (Figs. 14-16) showcase (white) women to ‘prove’ the beauty, and thus the superiority, of the white race. In this instance, these women are not shown to provide political or physical support for the movement, nor are they overtly sexualised. Their beauty is instead used to validate and spread the supremacist assertion of white superiority and embody the beauty white men should seek to ‘protect’ against threats from outsiders.

Fig. 14 (left) and Fig. 15 (centre), Fig. 16 (right). All photos are used to venerate the ‘beauty’ of white women and the white race. Fig. 16 compares a modern woman with a statue of antiquity, grounding this belief in white beauty in alleged historical fact.

Other images (Figs. 17-19) combine sexualised images of white women with overtly extremist content such as the sonnenrad, a Hitler speech and an Active Club sticker. While this ‘eye candy’ or extremist pin-up content is likely circulated for the enjoyment of male Active Club members, it may also assist with recruiting mainstream male audiences who may believe that involvement in the network begets romantic or sexual involvement with such women.

Fig. 17 (left), a woman lifts her shirt revealing a sonnenrad tattoo; Fig. 18 (centre), a woman lounges in her underwear while a video of Adolf Hitler giving a speech plays behind her; and Fig. 19 (right) a woman wearing an FBI jacket poses while a man holds an Active Club sticker.

‘Fashy Baes’

Over half of the analysed images containing couples – or ‘fashy baes’, to borrow a phrase from former white nationalist Caleb Cain – suggested that these men and women were in some way ideologically aligned. These images combined photos of couples with overt extremist symbols such as ‘88’ (Fig. 20), militant black metal music references (Fig. 21), and a Totenkopf (Fig. 22).

Fig. 20 (left), a couple embraces while outdoors, the man’s right thigh bears an ‘88’ tattoo; Fig. 21 (centre), a couple embraces, the man’s right sleeve shows involvement in militant black metal spaces; and Fig. 22 (right) a woman straddles a man working out, a Totenkopf flag is on the wall above them.

The women in these images are presumed to be tolerant of their partner’s beliefs, if not supportive of them. Similar to the Nazi eye candy images, fashy bae images may assist with the recruitment of both men and women who hope that involvement in the network could beget a romantic relationship.

Women with Agency

Over half of the analysed images contrast heavily with common right-wing extremist refrains of women as weak or passive. Specifically, these Active Club images show women as members of regular armed forces (Fig. 23), mixed martial arts (MMA) and hand-to-hand combat fighters (Fig. 24), as well as political activists (Fig. 25).

Fig. 23 (left), a female Serbian soldier holding a portrait of Saint Anastasia; Fig. 24 (centre), a female fighter binds her hands; on her right arm is a tattoo of the Othala rune; and Fig. 25 (right), an Italian female activist carries a copy of Diventa Rivoluzione, associated with the Italian fascist CasaPound group.

These images encourage women to fight for and support the Active Club network and the right-wing extremist movement more broadly, both physically and politically. Despite the network’s hypermasculine aesthetic, the Active Club network’s promotion of women in their activities signals that opportunities exist within their organisation for women looking to be more heavily involved in active far-right activism. This may expand the Active Club network’s reach among mainstream audiences.

Conclusion

Historically, white power and right-wing extremist groups have venerated traditional gender roles, strictly relegating women to the familial duties of being wives and mothers to the next generation of activists. However, this Insight found that 65% of the Active Club images analysed represented women outside of the familial domain of heterosexual relationships, instead shown in positions of power as brand ambassadors or armed fighters. The Active Club network’s ostensible acceptance of women’s political or ideological agency may be more palatable to young women interested in getting involved with far-right activism who aren’t willing to become wives and mothers.

The images posted to the Active Club Telegram channel may also signal to (white) women that they are desirable romantic partners. Such acceptance can appeal to many women who, like men, may feel isolated from their communities or mainstream society. However, it should be noted that elements of traditional gender roles and misogyny remain present in Active Club communications, as the channel was also replete with provocative, sexualised images of women.

For social media and tech companies, the ‘borderline’ violative nature of Active Club content may make mitigating the network’s use of their platforms difficult. While this Insight discusses an emerging aspect of Active Club content, increasing internal platform awareness of the network’s terminology, branding, and militant aesthetics in their differing portrayals of male and female members can assist with content identification.

Additionally, while the images above may not violate specific platform policies, the propaganda being promoted here exemplifies the online/offline dynamic of extremist radicalisation. Although the activities portrayed in these images originated offline, these photos have been co-opted online to further the Active Club network’s goals. As a result, Active Clubs may see a rise in women’s participation in offline activities. To further mitigate the spread of extremist activity, tech platforms such as Telegram may wish to increasingly consider the offline consequences of seemingly non-violative images in right-wing extremist spaces. Radicalisation occurs online and offline, and encrypted messaging applications in particular serve as vectors to fuel and proliferate pre-existing hate and produce narratives through even innocuous imagery.

Despite Active Club’s reputation as a hypermasculine space, their portrayals of women as active, strong, and desirable actors in the right-wing extremist movement may entice women who feel isolated from mainstream society or women who are simply looking to take a larger role within the white power and right-wing extremist movements. This is a concerning development within the Active Club network and the broader right-wing extremist community, as women’s more active involvement only serves to expand the group’s image and notoriety.