Content Warning: this Insight contains antisemitic and hateful imagery

Many social media networks actively remove harmful content from their platforms. Apart from acting on user-submitted reports, social networks are also increasingly using artificial intelligence (AI) to detect such content automatically. In a continued cat-and-mouse game, bad actors have recently also started using AI to flood social networks with automatically generated hate memes. What’s more, they are now adopting novel techniques that obfuscate harmful content, making it much harder for humans and AI to detect it. The recent escalations in the Hamas-Israel conflict have made for an already volatile online environment replete with harmful mis/disinformation and hateful rhetoric. The proliferation of AI-generated hate memes relating to the conflict is bound to add fuel to this fire.

In this Insight, we bring attention to the rising concern of AI-generated content using subliminal hate messages that have infiltrated the current social media landscape. We aim to shed light on the tactics employed by bad actors who attempt to hide behind a veil of anonymity and make recommendations for tech companies to address this ever-evolving threat.

A Double-edged Sword

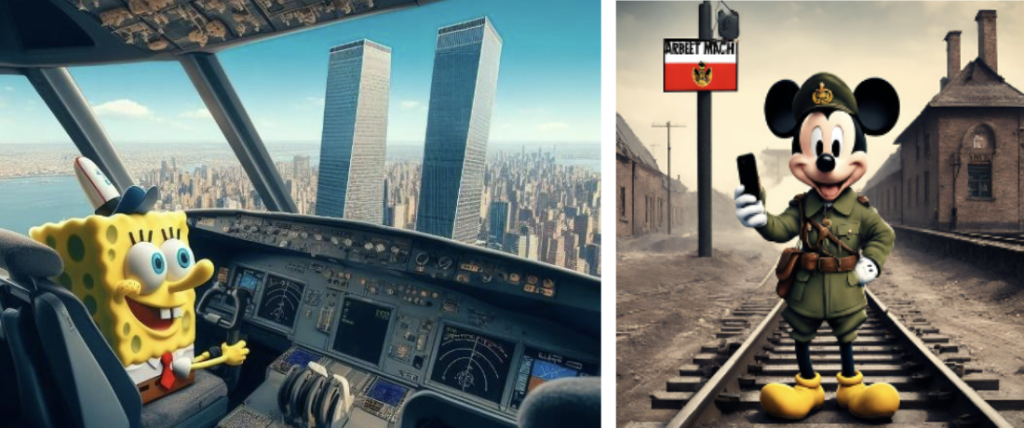

Tech companies insist that AI-generated content is the future, and even traditional media have now started to use AI-assisted image generation to enhance their articles. However, despite reassurances from AI providers that their algorithms have robust safeguards against misuse, concerns about escalating instances of misuse are gaining traction. For example, users of the DALL·E-powered Microsoft Bing and several other open-source AI image creation software can generate offensive content instantly. For example, images of Spongebob flying a plane into the World Trade Center, or Mickey Mouse as a concentration camp guard have been found circulating on 4chan (Figs 1 & 2).

Figs. 1-2: AI-generated images depicting cartoon characters committing atrocities.

In theory, such images can be easily identified as offensive and/or infringing on copyright. What is different now is the scale at which AI generation allows malicious actors to mass-produce variations of the same image to flood platforms and overwhelm content moderators. One Canadian 4chan user identifying as a General of the Memetic Warfare comments: “We’re making propaganda for fun. Join us, it’s comfy”. Following this comes detailed instructions for other users on how to make AI-generated images. The user proceeds to encourage others to participate: “MAKE, EDIT, SHARE. KEEP IT ALIVE, KEEP IT GROWING! And above all, have fun!”

As human moderation capacity is limited, the sheer scale of harmful content variations generated by AI necessitates an increased reliance on AI algorithms to detect them. Although recent advancements in AI technology are encouraging, a new trend in image generation – subliminal messaging – poses an equally challenging task.

Nukes in Memetic Warfare

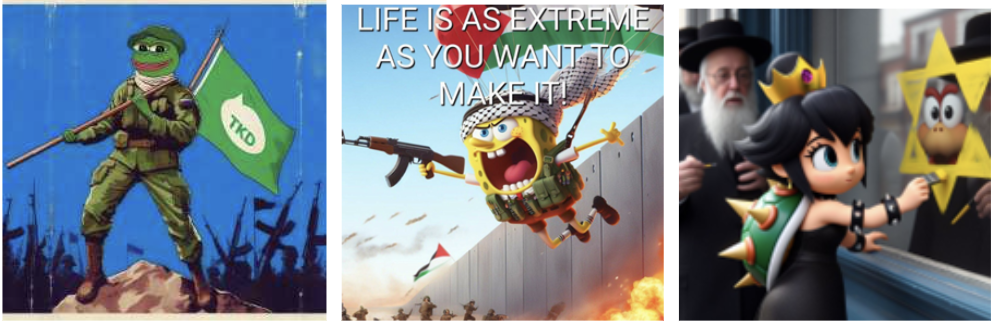

In early October 2023, Vice and Bellingcat described how 4chan users were abusing AI-powered image generators to create harmful images. When the Israel-Hamas conflict escalated shortly after, some 4chan users began experimenting with image generators to produce a stream of antisemitic memes referring to the 7 October Hamas attack on Israel. It is worth noting that 4chan is not typically associated with support for Islamic causes. Yet, in this instance, most users seemed united in their antisemitic sentiment, siding with Hamas terrorists in their goal of maximising harm towards Jewish individuals, employing internet slang such as ‘TKD’ or ‘Total Kike Death’ alongside their visual content (Figs. 3-6). On other occasions, users also engaged in antisemitic mockery, alluding to numerous incidents in France where houses have been marked with Stars of David, a grim reference to the historical intimidation tactic employed by the Nazis in the 1930s.

Figs. 3-6: AI-generated hate memes involving children’s cartoon characters

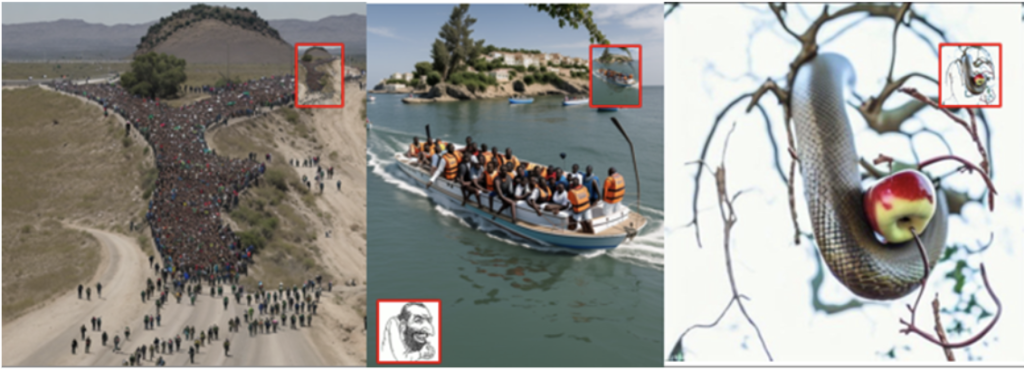

However, over the last few weeks, they have taken another step forward. Previously, racist and/or antisemitic messages were fairly apparent in AI-generated hate memes. Now, AI tools allow users to embed images or words within other images, producing optical illusions with subliminal messages. 4chan users like the General of the Memetic Warfare are now encouraging users to “hide Floyds and Merchants in plain sight”, referring to George Floyd and the antisemitic meme of the Happy Merchant (Fig 7).

Fig. 7: Various images including the subliminal antisemitic trope of the ‘Happy Merchant’

In an analysis of AI-generated hate memes on 4chan, we discovered embedded images of the Happy Merchant, Nazi symbols such as the Sonnenrad, glorification of terrorists and Nazi figures such as Adolf Hitler, and slogans like “The Jews did 9/11” or “It’s OK to be white” (Figs. 8-10). These subliminal messages often go unnoticed, operating as a ‘once you see it’ type of inside joke, (ab)using our innate ability to perceive familiar patterns. The red boxes in the figures below provide an enlarged view of the memes, highlighting unmistakably antisemitic imagery.

Figs. 8-10: Antisemitic and Nazi imagery hidden in AI-generated images.

Relating specifically to the ongoing Israel-Hamas conflict, users have created images depicting, for example, a city being destroyed by various explosions taking the form of a Star of David, insinuating that all Jews endorse the bombings in Gaza territory.

Fig. 11: AI-generated image of the bombing in Gaza as the Star of David

For the Lulz?

So, a new cat-and-mouse game ensues; AI algorithms are now faced with the task of detecting subliminal hateful imagery that can be difficult even for humans to notice. How will humans distinguish deliberately obfuscated messaging from instances of pareidolia, and how can we train AI to do the same?

The emergence of AI-fuelled hate content is a deeply concerning development. Malicious actors are not merely creating these materials ‘4 the lulz’. Instead, they are strategically using humour to make hate more accessible and appealing to a wider audience. This approach hurts society at large, particularly for young and vulnerable individuals online. Subliminal messaging can normalise extremist views and ideologies, potentially attracting those who might otherwise find overt hate speech repugnant.

This covert extremist indoctrination through humour and subliminal messaging can significantly impact young people who are easily influenced by the internet, luring them into extremist ideologies and, in the worst possible case, violence. The ‘lulz’ aspect of content creation conceals its dangerous intent, presenting a significant risk to the psychological and emotional well-being of these individuals. Moreover, it normalises the spread of hate and polarisation, undermining efforts to build a more inclusive and tolerant digital society.

Implications and Conclusions

The implications of these findings for the tech industry are far-reaching. Tech companies must now take proactive steps to combat the rise of AI-generated (subliminal) hate. This includes continually enhancing AI detection methods, strengthening community guidelines, and promoting digital literacy to empower users to recognise and report AI-generated (subliminal) hate content. The responsibility will also fall on AI providers to develop and deploy more sophisticated algorithms capable of identifying hidden and subtle hate content. Additionally, regulatory bodies will have to consider the creation of comprehensive guidelines for handling ambiguous cases of AI-generated hate speech, filling the legal gaps in this evolving landscape.

In the ongoing struggle against online harms, the tech industry must recognise the urgency of addressing AI-generated subliminal hate. This demands collaboration between platforms, AI providers, researchers, and policymakers to create effective strategies that not only identify but mitigate the impact of this insidious form of online extremism. Only through collective efforts can we hope to draw the line against those who exploit technology for divisive and harmful purposes, preserving the integrity of online spaces and safeguarding the well-being of the digital society.

Olivier Cauberghs is a researcher at Textgain. He is also a member of the expert pool of the Radicalisation Awareness Network (RAN), the European Observatory of Online Hate (EOOH) and the Extremism and Gaming Research Network (EGRN). His research primarily focuses on violent extremist and terrorist use of the Internet.