For over a decade, the Somali-based terrorist group al-Shabaab has prioritised media engagement as a critical component of its propaganda and recruitment efforts. In recent years, the group has doubled down on its social media presence using influencers to spread its narratives and official press releases/videos. The role that these influencers play within al-Shabaab’s operational hierarchy is not well understood, and as such, the current internationally-backed counter-al-Shabaab campaign is missing a critical angle.

This Insight explores the role that social media influencers play in al-Shabaab, highlighting their centrality to the terrorist group’s operations. These influencers move beyond ‘fanboys’ – supporters or sympathisers – to critical actors in support of the terrorist group’s activities and recruitment. To illustrate the role of influencers in al-Shabaab, I examine the case of the deadly May 2023 attack in Buulo Mareer, where al-Shabaab claims to have killed more than 130 Ugandan soldiers. I analysed al-Shabaab influencers’ activities on Facebook, Telegram, TikTok, and other smaller platforms over a three-week period surrounding the attack, and how their content and approach contrasts with communications from the counter-al-Shabaab campaign. The case highlights the role that influencers play, and how their control of the narrative online hampers the renewed efforts of the Somali government and international community to weaken the group’s grip in the region.

Al-Shabaab’s Communications Infrastructure

Al-Shabaab uses an expansive and interconnected network of communication platforms to distribute its content and promote its narratives. Web media, such as Somalimemo, radio stations, such as Al Andalus, and social media platforms and messaging apps such as Facebook and Telegram, all serve to propagate extremist content.

This array of communication platforms ensures that a range of potential recruits – from rural populations, diaspora, and citizens of neighbouring countries – can receive near real-time content from al-Shabaab. The power of this propaganda machine should not be underestimated; it floods those who express even a remote interest in anti-government narratives, or who have even loose connections to al-Shabaab-affiliated online networks, with friend requests, sympathetic content, and invitations to private messaging groups.

Social media in particular is a critical weapon in the group’s resilience strategy. Al-Shabaab’s growing online network, dispersed across major and decentralised platforms, allows the group to control the information space, showcase its strength during times of victory, retain its relevance during times of defeat, bolster recruitment, and plan and coordinate activities.

While the basic architecture of al-Shabaab’s communication operation is well-known, the role of social media influencers within this structure remains opaque. Relatively little is known about if and how communication is coordinated across platforms and with operatives on the ground, the network these influencers reach, and for what end.

The Role of al-Shabaab Social Media Influencers: Buulo Mareer

To showcase the strength and diversity of al-Shabaab’s communications infrastructure, and the role of influencers within it, this section will draw on the case study of Buulo Mareer.

On 26 May at approximately 5 am, al-Shabaab militants stormed an African Union Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS)’s Forward Operating Base (FOB) in Buulo Mareer. Ugandan troops operated the FOB, located in the Lower Shabelle region of Somalia. Al-Shabaab claimed to have killed 137 Ugandan soldiers that day, captured others, and seized weapons and ammunition, though these figures are likely exaggerated.

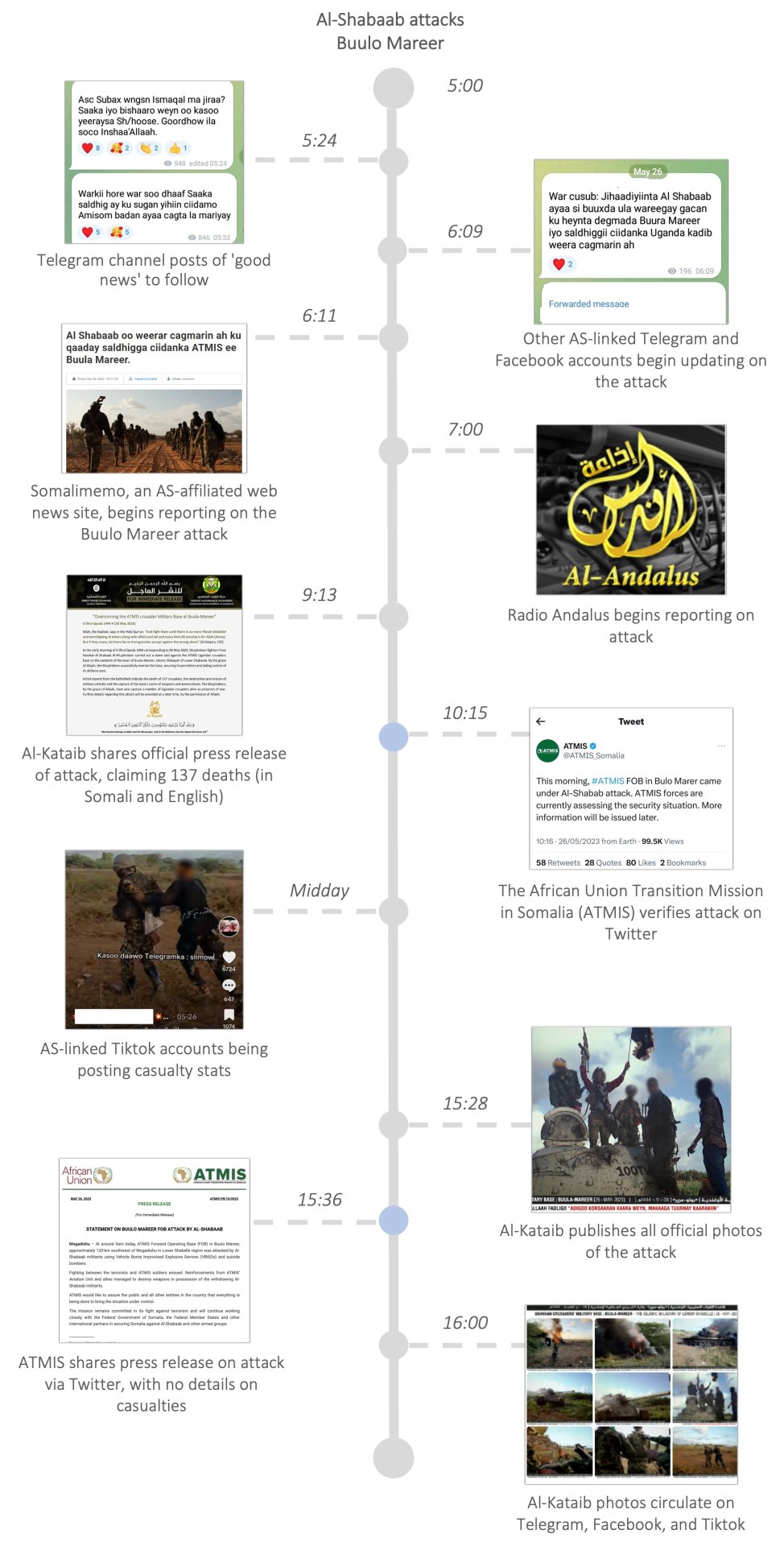

The timeline in Figure 1 shows key communication points from both al-Shabaab and the international community (the latter denoted by blue dots) from the day of the attack.

Fig. 1: A timeline of the Buulo Mareer attack

Al-Shabaab dominated the communications landscape that day, and social media influencers played a crucial role in generating and sharing content. Importantly, al-Shabaab-affiliated Telegram channels were the first to report on the attack, before the group’s web media sources. The timeline suggests that some influencers are in direct communication with al-Shabaab field operations. One Telegram account (linked to influential Facebook accounts) reported on the attack within minutes of the first gunshots, indicating that the account holder was made aware of attack plans prior to their execution.

Unlike Islamic State’s communications among its African affiliates, where official claims of attacks and associated photos can lag behind events by days or even weeks, al-Shabaab’s social media network appears tightly controlled and punctual. Influencers churned out near real-time updates on the attack, released photos of the event on the same day, and coordinated the narrative across an expansive array of influencers and platforms. During and immediately after the attack, these influencers linked followers to articles and radio programmes and stayed on message – reposting and reiterating content coming from top influencers and centralised channels, illustrating the tightly-knit nature of the group’s communication architecture.

The international community’s response to the attack appeared on the back foot in comparison. Before ATMIS had publicly acknowledged the attack via its Twitter page, al-Shabaab had posted on its social media platforms, reported on the battle over its popular media sources, and released an official press statement in both Somali and English. Then, before ATMIS shared their own official press release, the group’s media agency, al-Kataib Foundation, had already published official photos of slain and captured Ugandan soldiers to tens of thousands of viewers across their networks. One TikTok post from a popular influencer received over 300k views on a photo of a captured Ugandan soldier.

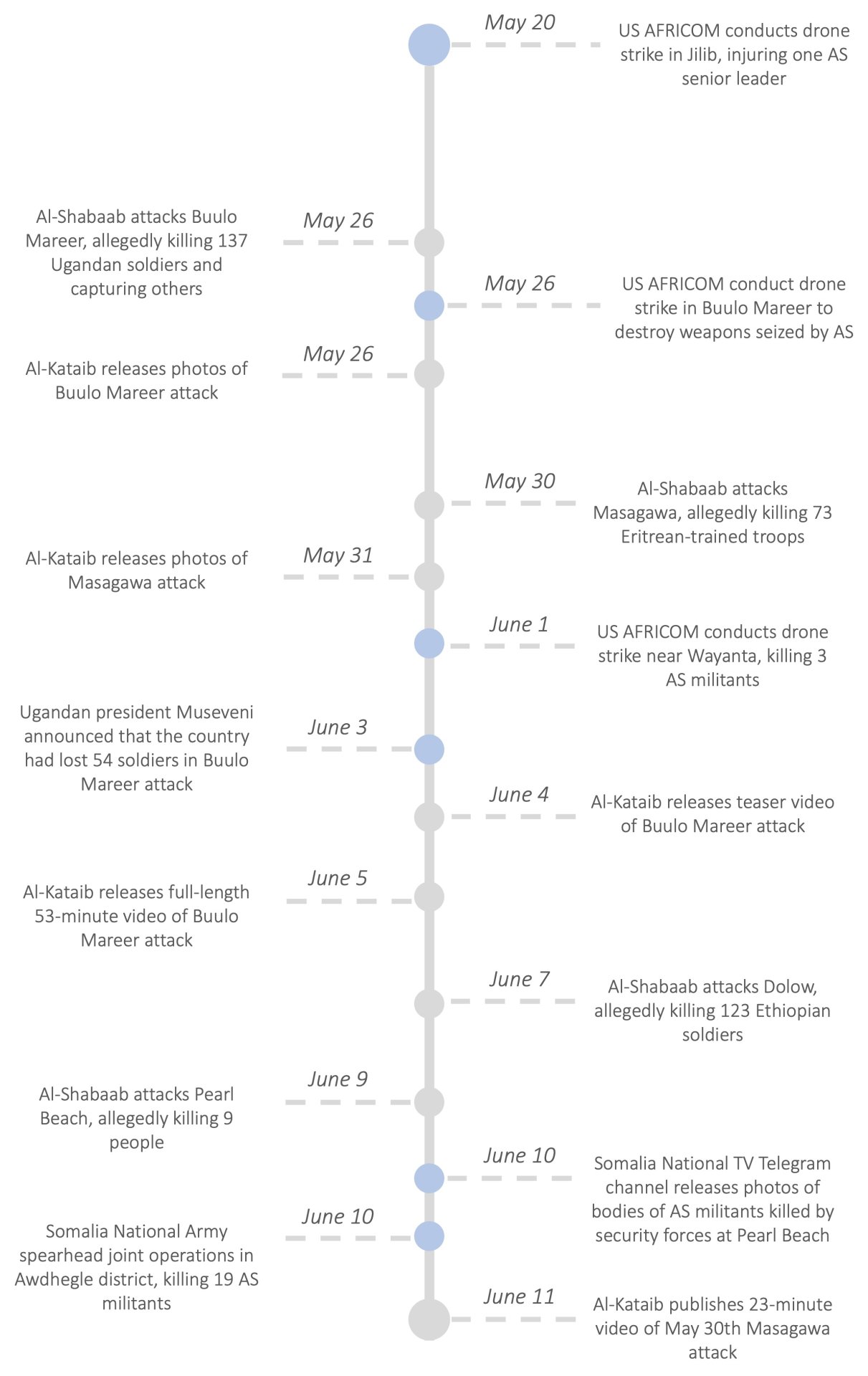

Fig. 2: Map of key pro-Somalia and pro-al-Shabaab events and communications

Zooming out to view the events leading up to and following Buulo Mareer, Figure 2 maps key pro-Somalia and pro-al-Shabaab events and communications over a three-week period. While the counter-al-Shabaab campaign continues to be presented by the Somali government and international community as making significant gains against the terrorist group, al-Shabaab controlled the social media landscape over this period. More communication is not always better, but in a post-truth world, having the first word and pushing that narrative excessively does have an impact. By the time Ugandan President Museveni communicated Uganda’s official casualty count from the Buulo Mareer attack, al-Shabaab had already proclaimed a body count of nearly three times the figures published by Uganda, circulated photos of dead soldiers, and mocked the Ugandan government and ATMIS for over a week.

Delayed reactions by ATMIS and the Ugandan government, coupled with their lack of specificity on casualties, sits in stark contrast to al-Shabaab’s well-oiled media machine. These delays and lack of details by the international community were met with scepticism by readers; this was seized upon by the terrorist group to perpetuate narratives of 1) ineptitude and defensiveness on the part of the counter-al-Shabaab efforts; and 2) strength and decisiveness on the part of al-Shabaab. With ATMIS scheduled to withdraw in 2024, al-Shabaab is well-placed to perpetuate these narratives.

The Influencer’s Arsenal

The case of Buulo Mareer underlines the extent of the group’s resourcing and coordination of its social media influencers, and the full-time nature of their content creation. Communications shared by influencers are in-sync with affiliated media sources. The rapid distribution of press releases and photos suggests that social media influencers are receiving updates from a centralised al-Shabaab media machine. Influencers with high visibility and large networks are rapidly creating and pushing content across multiple platforms at a full-time rate. This frequency of engagement suggests that influencers view this work as a full-time ‘job’, likely resourced by al-Shabaab funding.

These influencers are largely targeting a Somali audience. They produce content in Somali, a notoriously difficult language to moderate, and less frequently in Arabic, English, and Swahili. Their narratives focus on the group’s strength and anti-government/’anti-colonialist’ rhetoric. Their audience, though, is not limited to those within the borders of Somalia, as their online networks expand into other prime recruitment territories in neighbouring Kenya and Ethiopia, as well as diaspora living outside of the region.

Facebook and Telegram are the main distribution channels used by the influencers. They use these platforms to stabilise their online network by creating backup accounts and sharing cross-platform links, ensuring that content moderation or takedown sweeps have little to no impact. Even in the face of frequent takedown sweeps on Facebook, al-Shabaab influencers continue to create new accounts, as it remains an extremely popular platform across the African continent. From my own research, influencers are reaching tens of thousands of followers through these two platforms alone. They are also infiltrating TikTok and Element, among other decentralised platforms and messaging apps, and are re-engaging on platforms that had previously gone dormant for the group but remain popular on the continent, such as Twitter and YouTube, with influencers likely testing their commitments to continued moderation.

These accounts are not simply promoters of radical content – they are tactical operators within a terrorist entity, with the expertise and resources to grow their networks, avoid moderation, and leverage emerging technologies for their content creation. Al-Shabaab influencers are well-organised online to manipulate events and spin narratives to strengthen the group’s hand. This should be of critical concern to the counter-al-Shabaab campaign’s strategy for reducing the group’s influence.

Combatting Digital Jihad

The current counter-al-Shabaab campaign looks to tackle the group’s threat militarily, financially, and ideologically. This approach, however, misses the critical component of addressing the group’s continued influence online and on the ground, necessary for a comprehensive approach to longer-term stability in Somalia.

Al-Shabaab’s online network is operating as an extended frontline. Traditional security approaches might see selective wins in recapturing territory or reducing the group’s financial flows, but the battle for hearts and minds will continue to be waged over social media. Ignoring al-Shabaab’s control over these spaces risks strengthening the group’s ability to recruit and hold influence throughout the region.

Combatting this digital jihad does not lie uniquely in greater content moderation or takedown sweeps on social media platforms, for several reasons:

- Al-Shabaab is expanding its platform reach for dissemination, as part of its resilience strategy in the face of takedown sweeps and enhanced moderation tools among the larger social media platforms. For example, the Russian-operated platform Odnoklassniki (abbreviated OK.ru) has become a regular distribution channel for the group, likely because of its limited content moderation.

- Even within major platforms, al-Shabaab influencers are relentless in the face of account takedown sweeps. A key influencer was banned on Facebook six times during the three-week period used for this case study. The influencer created new accounts within a day of each ban, publicised them on his Telegram account, and rebuilt his network overnight. This ability to rapidly rebuild suggests that al-Shabaab influencers have the resources and technical know-how to subvert social media platforms’ security settings.

- Al-Shabaab is more effective at coordinating efforts across its social media networks than social media companies are at coordinating content moderation. Removing al-Shabaab content on one platform has little to no impact on the wider network, as noted above.

The counter-al-Shabaab campaign cannot sustainably weaken the terrorist threat without also combatting the group’s online engagement. This requires the campaign to view these digital jihadists as more than mere sympathisers and acknowledge the frontline role that they play in al-Shabaab’s resilience strategy. It also requires taking a multi-dimensional approach to reducing the al-Shabaab threat; one that looks beyond traditional security approaches to reducing the group’s influence on the ground and online. To do so, the campaign must understand the importance of controlling the information flow within social media platforms. In an increasingly digital world, even in conflict-affected states such as Somalia, significantly weakening a terrorist group’s physical hold is no longer enough.

Georgia Gilroy is a researcher and practitioner working on countering violent extremism, counterterrorism, and stabilisation programmes in fragile and conflict-affected countries in sub-Saharan Africa. She led the design and implementation of research strategies for donor-funded programmes in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia, and wider East Africa. For the past two years, Georgia has dedicated her efforts to understanding the interlinking dynamics of virtual and real-world extremist activities in the Horn and East Africa.