Petra Regeni is a member of the Extremism and Gaming Research Network (EGRN). EGRN brings together world-leading counter-extremism organisations to develop insights and solutions for gaming and radicalisation. For more information on EGRN’s research, please visit their website.

Introduction

For many, words like ‘high score’ and ‘accelerate’ mean nothing more than that – to win the highest number of points, and to push the gas pedal on your car. For others, those words paint a different depiction of reality. The versatility of language allows the manifesting of new trends and popularising phrases that may have once been on the fringe. Narratives, or portrayals of events and stories, are how we shape and make sense of our reality.

In the world of extremism, gamification and accelerationism, narratives about high scores, Saints, acceleration, collapse, and replacement paint a dark version of reality. On their own, gamification and accelerationism have become increasingly worrisome trends in the terrorism and extremism worlds. As a string of terrorist attacks has demonstrated, the two are increasingly interlinked in the ideological framework of assailants and the potential radicalisation of future violent extremist attackers.

Gamification I take to mean “the use of game elements in non-game contexts,” which is merely one aspect of the gaming and extremism nexus. Past research has highlighted at least six key video gaming strategies related to extremist activities, which include gamification of terrorist attacks. These also encompass the creation of bespoke video games/modifying mainstream games, in-game chats, gaming-adjacent platform communications, and gaming cultural references.

Creeping into some of the darker corners of the internet where extremist narratives manifest, you start to find more-and-more gaming-infused and accelerationist narratives. Most generally, accelerationism posits that complete societal collapse is the only solution to address socio-political problems (often ones spanning the world). They justify the utilisation of violence to achieve their ends in hastening the end of times. For accelerationists, a Machiavellian ‘the ends justify the means’ applies.

This convergence is increasingly dangerous for two particular reasons. First, gamified violent attacks carried out with accelerationist aims and narratives have multiplied, often inspiring subsequent generations of attackers. Second, online users gamifying narratives about accelerationism, often in response to attacks, is increasingly becoming mainstream.

By focusing primarily on militant accelerationism inspired by white supremacist views, this Insight explores the ways accelerationist narratives are framed in gamified terms. The point isn’t necessarily to accelerate the radicalisation of users, as research remains nascent about the effect of gaming on radicalisation pathways, but rather to frame reality itself as merely a game to immerse oneself in.

In-Game Accelerationist Narratives

Bespoke video games by extremist actors have been designed around accelerationist narratives. Although research has not proven a robust link between playing a game and offline actions or ideologies, such as between playing violent video games and engaging in offline violence, we know that games are immersive social online environments that are increasingly exploited by violent extremist actors and for extremist purposes. Games may not themselves radicalise users playing them, but we can question how the storyline of a game might impact gamers’ views.

As early as 2002, narratives around what would come to be called the Great Replacement theory were infused into games. The American white supremacist group National Alliance released the video game Ethnic Cleansing, a first-person shooter game, where users could play as a neo-Nazi skinhead or a Klansman in a ‘race war’. Their aim: to kill ethnic minorities, namely African-American, Latino, and Jewish people, and overthrow the Israeli government – or in the storyline of the game, “save the world from domination”. The language in the game itself was plagued by racial stereotypes. As the player shot Latinos, dressed as bandits to adhere to racialised scripts, they would shout “I need to take a siesta”.

Ethnic Cleansing was not a standalone endeavour. National Alliance later released video games with similar underlying storylines: from White Law to ZOG’s Nightmare (which included not just one but two versions). National Alliance was also not alone in the production of accelerationist narrative games. The group also made tabletop games such as Racial Holy War along a similar storyline – to unite as “white warriors” and “cleanse the world” of enemies, again ethnic minority groups, and restore a “glorious White Empire”.

I would note that white supremacists are not alone in bespoke video game production framed around narratives of social collapse. Jihadist groups also capitalised on the popularity of games, infusing them with their own extremist rhetoric. Around the same time as white supremacists, Hezbollah released their own video games such as Special Forces, immersing players in a fight against the Israeli Defense Forces. The game featured a second edition as well. Though these weren’t fused with accelerationist narratives, it was an early start to leveraging gaming in the violent Islamist sphere as well.

The Islamic State, too, capitalised on the use of games to frame their narratives and ideological aims by seeking to ignite a ‘Holy War’ or ‘Holy Jihad’. Trailers using clips from the popular Grand Theft Auto video game, although not created by IS media centres, were leveraged as propaganda. In the later modified game, Salil al-Sawarim, users could play as IS members engaged in combat against American forces in carrying out their “call to jihad”. For IS, the framing of the game narratives served not only as a tool to radicalise and recruit people online, but to show that “this can be you in reality, if you join us in Syria.” There’s no doubt that IS recruited foreign fighters under the adventure-seekers category – those attracted by the prospects of excitement and glory – convincing them to take the game offline and play in reality.

Slightly outside of the bespoke gaming realm, IS filmmakers also created videos displaying a tactic of the gamification of propaganda. Visuals from games like Grand Theft Auto and Call of Duty were reproduced in propaganda films with IS audio including the Clanging of the Swords and visuals of the black Caliphate flag and footage of IS fighters. In essence, it used gaming features and framing to reach more diverse populations online and accelerate the call to fight with IS in Syria and Iraq in their so-called holy war.

The exploitation of games in this sense has become a means to spread accelerationist narratives. Leveraging pop culture to reach new people, often targeting younger generations, through the framing of racial and holy wars in gaming terms continues to be an arsenal in the extremist toolbox today.

Out-Game Accelerationist Narratives – Gamified Attacks

The events of Christchurch in March 2019 fundamentally altered the right-wing violent extremist landscape and continues to have rippling effects today. When Brenton Tarrant strapped on a GoPro headcam, holding a semi-automatic rifle, turned on Facebook Live, and attacked innocent civilians in Al Noor Mosque, he redefined the gamification of terrorism in an egregious way. Fueled by the Great Replacement ideology and vehement hatred for ethnic minorities, whom he blamed for the shrinking majority of white populations in New Zealand and Australia, he live-streamed his attack in which he emulated a first-person shooter game. His overarching aim was to create a ripple in society in the hopes of igniting a societal revolution.

What Tarrant likely didn’t predict is the lasting impact he would have. Not long after the Christchurch attack, copy-cats inspired by Tarrant soon followed – from the attempted gamified attack in Halle, Germany, to the most recent May 2022 attack in Buffalo, USA. Others have hailed Tarrant as an acceleration inspiration for their own attack, even if they did not gamify it, there is growing evidence that relevant discourse was subsequently framed in a gamified manner.

Out-Game Accelerationist Narratives – Gamified Discourse

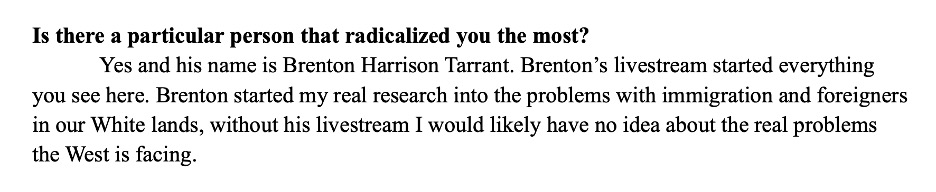

The Buffalo shooter, Peyton Gendron, wrote in his manifesto that the Christchurch “livestream started everything you see here” (Fig.1).

Fig.1: Excerpt from Peyton Gendron’s manifesto

On his own accord, Gendron explained a key motivating factor for his attack in Buffalo. His manifesto was also plagued with numerous accelerationist narratives and was live-streamed on the gaming-adjacent platform, Twitch, while seemingly emulating a first-person shooter game aesthetically.

Looking outside the realm of white supremacist attacks and assailants’ manifestos, message-board platforms feature their own world of gamified framing of accelerationist discourse linked to the Great Replacement idea. Some of this discourse has inspired subsequent assailants, by their own admission, while others simply discuss real life as if it was a game.

In the wake of the Bratislava attack that targeted and killed 2 people from the LGBTQ+ community, the assailant, Juraj Krajcik, then went online to the image boards‘4plebs’ and ‘4chan’. There, and in his manifesto, Krajcik explained that the actions of Tarrant and Gendron helped cement his great replacement views and his desire to accelerate the “social revolution” by targeting a minority group. Krajcik himself did not perpetrate a gamified terror attack nor does it appear that he intended to.

What it Looked Like on Message-Board Platforms

The responses to Krajcik’s online thread show how other users’ discourse gamified the framing of the attack in different ways, with some responding positively, and others critically. First, it is important to understand references to ‘high scores’ and ‘leaderboards’. In referencing and evaluating the prominence of a white supremacist attack, leaderboards are used to rank past perpetrators: much like a game. Some boards merely factor in how many people were killed – which is equated to a numerical ‘score’ – while other ones also consider the modus operandi, the ideological motif of the attacker, and more. Brenton Tarrant, along with the 2011 Norway accelerationist attacker, Anders Behring Breivik, who killed 77 people linked to political families including children, often ranks on the top of such leaderboards. Both have a significant ‘high score’ but also a revered method of attack and, in very different ways, adhered to a militant accelerationist ideological conviction that continues to inspire assailants today.

Leaderboards have been transformed into images or memes, displaying assailants’ scores, their motivations and beliefs, and ultimately their given ranking. In other places these leaderboard rankings are more actively discussed by users, debating whether a ranking is too high or too low, why that might be, and explaining their perspective on their score. In any case, leaderboards and high scores can create an illusion online that violent attacks, in reality, are merely a game – or otherwise diminish attacks in reality to one framed as a game.

In the discourse on message-board platforms, live-streamed attacks have become highly regarded. Tarrant, and later Gendron, were awarded more notoriety and higher ‘ranks’ for gamifying their attack through live-streaming.

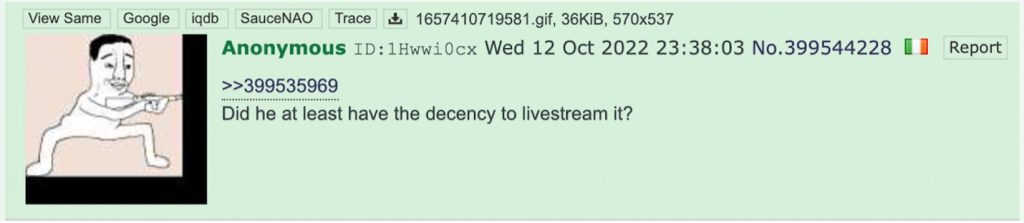

In the case of Krajcik, discourse following the news of the attack diverged, even on the ‘4plebs’ and ‘4chan’ boards where Krajcik was active after his attack before he took his life. Critical discourse ‘faulted’ him for not gamifying his attack, implying a live-streamed attack would have been more highly regarded (Fig.2).

Fig.2: Screenshot from 4plebs thread following the Bratislava attack

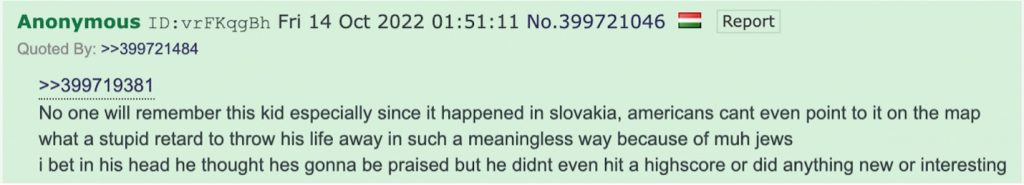

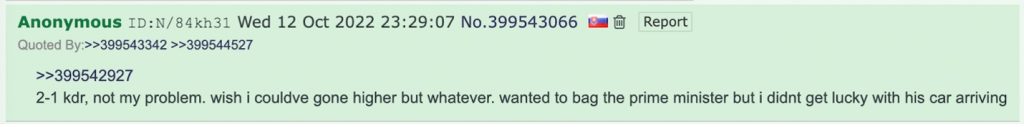

Criticism of his ‘score’ was also popular. Two victims were reduced to numbers deemed unimpressive in the ‘4plebs’ and ‘4chan’ discourse that denigrated victims to the score of 2 though posts belittling his ‘score’ and aims (Fig.3 & Fig.4).

Fig.3 & 4: Screenshot from 4plebs thread following the Bratislava attack

Gamified framing reduces not just the attacks and victims to numbers, but also the attacker’s aims, ideology, and modus operandi to a rank or score. Krajcik also gamified the framing of his attack. Replying to people on the ‘4plebs’ board, he acknowledged his ‘low score’, going further to even state that the intended target should have been someone of political prominence. In essence, someone with higher blame for the problems he saw in society, someone whose death could have more relevance for accelerationist aims (Fig.5). In the board, Krajcik writes that:

Fig.5: Screenshot of post allegedly by the assailant, Juraj Krajcik, on a 4plebs thread following the Bratislava attack

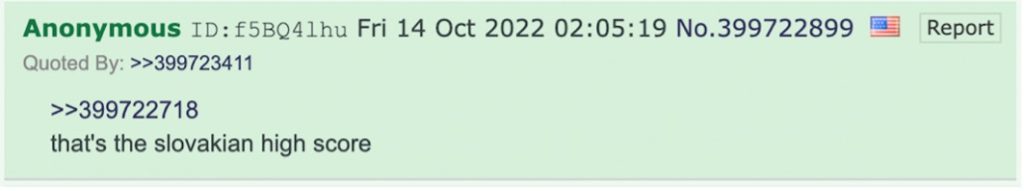

The gamified discourse on ‘lower ranked’ attacks, however, is not always negative. Although notably scarcer, some comments frame ‘high scores’ around the context – for instance, geographical region, personal characteristics (such as age or ethnicity), and more. In the case of Krajcik, the ‘positive’ narratives framed his attack as “the Slovakian high score” (Fig.6). So, while it may not be the highest”, it was contextualised to still be an “achievement”.

Fig.6: Screenshot from 4plebs thread following the Bratislava attack

Fig.7: Screenshot of 4chan board about Krajcik being named as a “saint” following the Bratislava attack

Final Thoughts

The topics of gamification and accelerationism have crossed paths in many ways over the last half decade and arguably even before that. From in-game narratives inherently promoting an accelerationist ideology and discourse, to out-game narratives on platforms like ‘4chan’, ‘4plebs’, and many more, wherein online users discuss and frame previous attacks in gamified terms.

The convergence of gamification and accelerationism has further exposed future risks of violent extremism. It is contributing to the desensitisation of real-life violence and dehumanising victims rendering them into mere numbers/scores. Not only does such framing serve to normalise extremist rhetoric but it ultimately ends up glorifying terrorists, and even motivating further attacks as assailants could gain notoriety and sainthood status themselves. Gamified narratives can both provide a foundation upon which accelerationists can radicalise others and radicalise themselves to carry out violent attacks.

The proliferation of such narratives online gives a louder voice to accelerationist rhetoric and interlinked conspiracy theories that can be used to introduce and ultimately indoctrinate people into accelerationist ideologies, most notably the Great Replacement theory. It becomes more widespread, and as it spreads, the larger the chances are that it becomes a part of the mainstream. As we have already seen with mainstream news outlets referencing Great Replacement ideas, echoing the narratives underlying terrorist attackers’ ideology, dangers of the further spread and dilution of what is an extremist ideology into something more relatable is immensely worrisome.

Intermixing gamification and accelerationist narratives highlights another threat: copycat and contagion effects. Gamified attacks and narratives and the spread of accelerationist rhetoric hold a certain appeal online. And moreover, past assailants growingly inspire the next generation of assailants, some acting as so-called innovators of violent extremist attacks, like Tarrant, while others become a product of the innovators that inspired them.

While it remains unclear what exact role these narratives have in the radicalisation pathways of individuals, it is becoming evident that such discourse and language among users’ online play into the ideologies of white supremacist attackers, serving a role of glorifying attacks and also inspiring another generation of attackers – as well as those merely observing and/or engaging in discourse online.