Introduction

Terrorist acts often confront the public with gruesome images and unthinkable suffering. Understanding the motivations of terrorist attacks is no easy task. In the wake of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, Robert Pape wrote a foundational essay, offering a clear interpretation of their rationale. Pape argued that terrorism follows the same “coercive logic” as conventional forms of warfare: just like regular combatants, terrorists seek to obtain specific, limited concessions from their targets, often of territorial nature. Their deaths, no matter their excessive brutality, still serve limited political causes. Media, in this equation, act as violence amplifiers: recording and diffusing terrorist violence becomes a tactical way to enhance pressure on target governments. Pape’s account gained much traction in security studies, and its assumptions still provide the theoretical backbone of many contemporary policy papers in Europe and North America.

Yet, contemporary ‘lone wolf’ terrorism does not fit this logic. Actors such as the Christchurch mosque shooter seek no concessions, nor do they have any specific political calculations in mind when conducting their attacks. In his manifesto, the shooter, who was not affiliated with any single extremist group, rants about his aim of accelerating racial tensions into an eventual ethnic-religious war. How, then, can we hope to understand – and stop – seemingly incomprehensibly isolated acts of terrorism?

In this Insight, I argue that explanations of contemporary lone wolf terrorism must start by rethinking the way we understand the online, social media-based environment. Rather than seeing social media platforms as passive stages on which the struggle for and against radicalisation and terror is played out, we should allow for the possibility that media demonstrate a particular form of agency, resembling both a layered assemblage and a lure. Through non-linear and complex media, lone wolf terrorism displays two functions: one of connection and one of performance.

Understanding Media: The Extensions of Terror

Most accounts of stochastic or probabilistic terrorism – such as the dedicated report on far-right violence published by the European Commission in 2021 – recognise its unstrategic nature, but still retain an element of linearity. The model they propose is simple: the stochastic terrorist first introduces a potentially harmful message within a given media space (i.e. social media) at an ‘input point’, then, the message finds reception among a minority of particularly susceptible individuals through their devices (the ‘output point’). A minority of these vulnerable individuals increasingly engage with the content, become radicalised, and then ultimately plan and carry out attacks. Fighting lone wolf terrorism thus does not entail the removal of strategic incentives for its use – as one would expect in Pape’s model – but rather an effort to reduce the dissemination of messages that can turn vulnerable individuals into possible attackers.

Media still work as linear channels and amplifiers for terrorist information. Admittedly, algorithms and platform mechanics feature in this equation by altering the probability that the message will go viral and be received by its intended audience. However, these accounts significantly underplay the complexity and incompleteness of the information received by the possible lone wolf terrorist. In the manifesto of the Christchurch mosque shooter and other attackers, one finds references to extremist material, or what policymakers commonly understand as ‘stochastic terror messages’, intertwined with references to video games, music, and other seemingly unrelated cultural material. Readings of these contradictions have pointed to their post-ironic nature: in referencing the videogame Spyro as a radicalising factor, the Christchurch shooter mocked a classic motif in Anglo-American journalism linking video game playing and violent outbursts.

However, flattening this content to the level of irony undermines two fundamental aspects, and, crucially, two dimensions of this brand of social media-inspired terrorism. These dimensions can be broadly defined as the ‘screen-output dimension’ and as the ‘performative dimension’ of lone wolf terrorism.

As mentioned, social media offers incomplete information. McLuhan – who associated media’s ‘temperature’ to the amount of cohesive sensory information they provided – would have called social media a ‘cold’ medium, as users are forced to make connections and build patterns of meaning independently. The screens of their devices provide them with little guidance in doing so, especially compared to other media. Televisions, for example, offer a narratively coherent, self-containing, self-timing audio-visual experience. Social media, by contrast, presents itself to the user as a mosaic of different, unrelated posts distributed on a feed or board – a model shared by, among others, Instagram, Twitter, Facebook and Reddit. The repetitive act of scrolling not only adds a tactile dimension to the experience but also allows the audience to set their own speed of engagement.

Further, Nick Srnicek’s book Platform Capitalism shows how the economic model of social media platforms is increasingly rooted in the extraction, processing and sale of the data generated by repeated user engagement. Algorithms, here, become content curators by favouring images and sounds that they predict will be consumed quickly and capture users’ attention based on their previous choices. This is a two-way street: not only does the platform encourage repeated behaviour, but it also conditions content producers to discriminate towards posting potentially viral material.

Performing the Screen through Terror

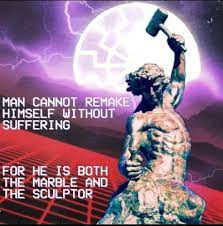

The complex cultural assemblages that are present in many attackers’ manifestos and in other extremist content – mosaics of memes, movies, video games and other cultural material – reflect the lack of unity or direction found on the homepages of Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram. Radical violence copies, in its incoherence, the screens on which radicalisation can occur. Examples of this include, for instance, ‘fashwave’ memes, which pair the neon aesthetic derived from 80s music videos, the movie Tron, and the Far Cry 3 DLC ‘Blood Dragon’ with traditionalist messages taken from philosophers like Julius Evola, or the ‘jihadi cool’ content, which mixes Sharia with hip hop and urban culture.

Fig 1: A ‘fashwave’ meme combining Traditionalist elements and a quote by French Nobel prize winner, eugenicist and Vichy collaborator A. Carrel with a 1980s-inspired aesthetic reminiscent of old VHS tapes and arcade video games. The ‘Black Sun’ in the background is a typical motif in Neofascist-Evolist sub-cultures and also appears on the cover of Christchurch shooter’s manifesto. Source: Facebook.com

This point leads to another insight: in conducting their attacks, lone wolf terrorists who have been radicalised online increasingly perform a media-related function. Writers and journalists have already identified how the Christchurch, Halle, and Buffalo attackers live-streamed their actions from a ‘POV’ angle reminiscent of first-person shooter video games like Call of Duty and Doom. Likewise, ISIS propaganda videos make repeated references to the Call of Duty and Grand Theft Auto franchises (and, more broadly, to Hollywood-type action movies) – often featuring real execution or attack footage. In most cases, the resulting content is uploaded online – in the case of ISIS, packaged in a deliberately ‘vital’ manner in the hope of driving more engagement.

Fig 2: An ISIS-made ‘jihadi cool’ meme featuring a mix of Islamist and Call of Duty references. The photo also appears to have been slightly ‘deep fried’, that is layered under a series of filters to make it grainier; again, an otherwise unrelated but (formerly) viral practice on meme pages. Source: Universiteitleiden.

The screen, here, is vital. While old interpretations saw screens as separating real and mediated violence, new studies show how this relationship is more complex. Holmqvist’s study of drone warfare operators demonstrates that screens can show viewers more violence than those who witness it live. Screens, here, extend the body of their operators, and, with their easy-to-use controls akin to those of a video game, allow for the endless repetition of violence, effectively crystallising it away from the blurriness of the present moment. Unaffected by adrenaline, emotions and the limits of human bodies, screens show more than everything and with hyper-real clarity.

A similar logic, I argue, can be extended to the relationship between mediated terror and lone wolves. Recording violence and sharing it online allows for violent acts to be endlessly repeated. In this sense, the medium of the screen acts as a ‘lure’ and mobiliser of further extremist action by flattening and alienating the real experience of the terror act into a mediated thing that can be re-deployed – potentially facilitating imitation and ideological convergence – by other stochastic terrorists.

Moving Past Linearity

This view of stochastic terrorism and media admittedly presents a difficult, if not bleak, perspective for policymakers and practitioners determined to stop the cycle of self-radicalisation and violence. It is not my intention to suggest that (in many cases, demonstrably effective) methods of countering and preventing terrorist violence ought to be abandoned or rethought. Rather, moving past linearity in the area of disrupting digital lone wolf terrorism means creating new opportunities for the study of media as actors, rather than simple ‘stages’ on which violence is made possible and real.

Linking terrorist action and media consumption through the prism of screens and performance offers opportunities to tackle the internal incentives and functioning of online platforms, and social media websites in particular, as offering independent security risks. This is, in itself, not unprecedented: social media usage and repeated user engagement have already been convincingly analysed in the context of the facilitation and prevention of other harmful behaviours, such as eating disorders (EDs). Allowing for dialogue in the field of counterterrorism and violent extremism studying the media environment in a holistic and non-human-centred manner may yield future opportunities for prevention and response.

Screens, and the ways they assemble different cultural materials, need to become the subject of more analysis, as do the extent to which repeated, interactive actions such as scrolling are linked to ‘offline’ behaviours. Likewise, tech companies may have an important role to play in conjunction with policymakers in analysing possible effects of juxtaposition through the homepage or feed models, that is analysing assemblages rather than single images. Finally, the inhibition of the spread of possibly radicalising material remains important. Here, a fundamental improvement will necessarily involve the revision of the ‘black box’ model of algorithmic content personalisation, in order to develop a more holistic set of tools to prevent the becoming ‘viral’ of harmful and violent media. A better understanding of how and why algorithms recommend specific content, and how that content interacts with the other material of the feed’s ‘mosaic’, is extremely important to develop a more inclusive theory of violence and radicalisation.

Manfredi Pozzoli is a master’s student in International Affairs at LSE and SciencesPo Paris, as well as a research fellow at Think Tank Trinità dei Monti, in Rome, and an analyst at the Nicholas Spykman Center for Geopolitical Analysis. His research interests include the intersection of social media and terrorism, especially in the context of Europe and North America, and the development of covert psychological operations in the Cold War. His article on the origins of the stay-behind network Gladio is pending publication in Strife Journal.