Introduction

“They tolerated the ISIS in Marawi. ISIS sympathisers!”

“They deserve it. They were handlers of killers, carnappers, drug lords and worst of all they are sympathisers of ISIS!”

“During the Marawi siege, we were looking for a place to stay.. But when the owner learned that we are Meranaos from Marawi, they rejected us.”

“They accused us of being ISIS sympathisers. What the hell! Stop spreading hate, people!”

Research indicates that violent extremists have been using digital platforms as breeding grounds for online recruitment. A report also suggests that hate speech proliferates on these digital platforms. Young people are the most active users of the digital space, making them more susceptible to online hate and vulnerable to recruitment by extremists. In the Philippines, about 21 million digital platform users are between 18-24 years old. The country is also reported to be one of the most prolific users of social media in the world.

Mindanao, the southern region of the Philippines, is described as home to the second-oldest conflict in the world. The conflict spans 450 years and is rooted in the quest for self-determination among the Islamised indigenous tribes. The self-determination movements’ ideologies and tactics have varied over time, however, parts of the movement have now aligned themselves with the Islamic State. In 2017, an ISIS-affiliated group attempted to take control of the country’s Islamic capital, Marawi City. Thousands of people, mostly Moro Muslims, were displaced and took refuge in Christian communities. As a result of the Marawi siege and the displacement of Moro Muslims, online hate speech from ordinary netizens – not necessarily extremists – targeting Muslim communities increased. Muslims were accused of being sympathetic to the ISIS-inspired militants.

This Insight draws on a case study of a group of university students from Muslim Mindanao in the Philippines who implemented a project that aimed to counter Islamophobic hate speech online. This project asked: how can digital platforms be utilised in challenging violence, extremism and hate speech, and what role do young people play?

Countering Online Violence and Hate Speech

Between May and October 2017, a militant group calling itself the Islamic State lay siege against the city of Marawi in Mindanao, southern Philippines. While research has often focused on the online radicalisation of youth, this Insight examines a novel project among Mindanao youth to counter the online hate they experienced as a result of Moro displacement during the Marawi siege. This project demonstrates the capacity of youth to develop programs using social media to reduce hate speech and also build resilience among youth by building community.

Responding to the proliferation of online hate speech, a group of students from Mindanao State University-Iligan developed an online project aimed at spreading positive messaging on digital platforms. The students first conceptualised the project at a time when the memory of the Marawi siege in May 2017 was still fresh. The project’s main goal was to address Islamophobia-linked hate speech online through the use of social media. Social media platforms used in the project include Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. These three platforms are common in the Philippines. Facebook is more accessible in the country and is more popular across ages and regions in the Philippines than the other platforms. With social media, youth proponents can promote their initiative and spread the message to their friends and family back home. At the same time, they were able to update their parents and guardians even if they are away from Mindanao.

One way to counter the proliferation of online hate speech is to flood online platforms with positive messaging. The project, named IslamNotphobia, aimed to counter negative narratives surrounding Islam circulating on social media. The group, named Team Pakigsandurot, a Binisaya term which means ‘connections’, comprised students from different cultural backgrounds: Moro Muslims, Christian migrants, and indigenous communities. It is also fitting to the Mindanao context, characterised by the presence of different cultural groups. The project is part of the global digital challenge co-implemented by the U.S. State Department, Facebook, and EdVenture Partners, dubbed as Peer2Peer: Facebook Global Digital Challenge.

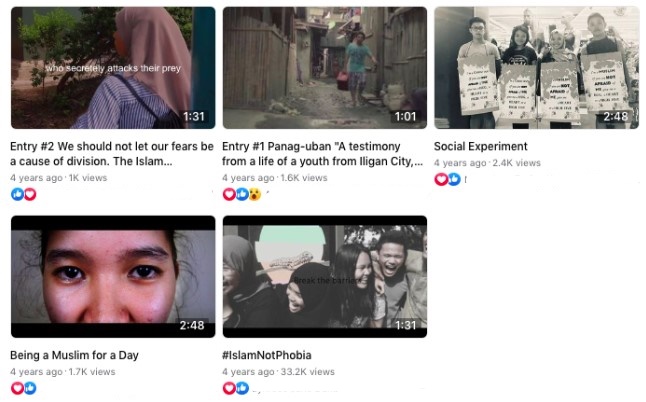

A major component of the project is positive messaging through video making. The students made short videos targeting Mindanaoan youths portraying positive interactions between Muslims and non-Muslims at the university. The actors in the video are the youth implementers themselves, together with their university classmates and friends. Not only did the video give insights into intercultural collaboration, but it also encouraged some university youths to be part of the team. Additionally, the team also had a ‘Muslim attire for a day challenge’. Here, female non-Muslim team members were invited to wear hijabs and Muslim dress for the entire day at school. The aim was to provide a first-hand experience for non-Muslim female members of how interaction with other classmates would be if they identified as Muslim. Three non-Muslim female team members participated in the experience. These experiences were then captured through videos and photos posted on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Fig. 1: Some of the group’s online strategies

Another strategy was a social experiment in a shopping centre in Iligan City. Iligan City is a multi-cultural community where Muslims, Christians, and indigenous peoples co-exist. In one corner of the shopping centre, two team members stood with placards. One has a placard that says, “I’m a Christian. If you’re not afraid of me, give me a hug, a heart, or a high five,” while the caption of the other says “I am a Muslim, will you do the same?” For four hours on a busy weekend, the social experiment captured the attention of onlookers. At first, there were no takers. After over an hour, a couple of mall visitors took the challenge and start giving hugs, high five, or heart-shaped paper. The experiment was captured in a video, edited, and posted on social media platforms.

The team also called for photo submissions open to all Mindanao youths. The photos captured the attention of the Mindanao audience. They also captured international attention when academics from an Australian university selected one of the team’s photos for a cover of a book about the Philippines’ socio-political studies. Over 150 photos were submitted, utilising captions on intercultural cooperation, diversity appreciation, and youth engagement. These photos were also displayed in an exhibit at the University. The exhibit features youth-inspired designs and colours which captured the attention of the university students, faculty, and staff.

In a post-evaluation of the project, 87.8% of those contacted said that the project helped youth understand cultural diversity and the importance of cultural respect and understanding. Both online and offline strategies of the project captured over 1.3 million online engagements on Facebook, 13 thousand impressions on Twitter, and 111 followers on Instagram.

Conclusion

In Lederach’s (1997) peacebuilding paradigm, young people are considered to be most connected to grassroots, community-level work among those who have had first-hand experience of conflict. With young people being so active on social media, using these platforms for peacebuilding can be an effective way to connect young activists. Technology can be a space for terrorists or extremists to recruit youth. However, this project indicates the potential for youth to not only build resilience towards extremist messaging but also be active participants in generating greater social cohesion and combating online hate speech. Although this project was small, the impact was considerable; five students were invited to Washington DC to present their findings before the representatives of Facebook, Edventure Partners, and the U.S. State Department.

Fig. 2: Youth representatives in Washington DC

The reconstruction of Marawi City is ongoing. Most Marawi residents have returned to the city. From time to time, online hate speech occurs but is less rampant than during the siege. However, threats of violent extremism continue to challenge the community, afraid that another attack will happen in Marawi or elsewhere in Southern Philippines. Interventions, both online and offline, to prevent extremism in the region need to continue to engage with youth. Youth should not only be the target of such interventions but have proven their capabilities in developing successful projects.

Primitivo III “Prime” Cabanes Ragandang is a PhD candidate at The Australian National University (Canberra, Australia). His PhD thesis explores community resilience through collective memory and transgenerationality, with the case of Bangsamoro in Mindanao of Southern Philippines. He is the founder of BHOLI Youth Centre, a youth-led organisation that offers after school programs to students Pre-K-12 in Northern Mindanao in the Philippines. In 2021, he completed his co-edited book on youth, peacebuilding, and sustainability, published through the Young Southeast Asia Leaders Program of the United States Mission to ASEAN.

Twitter: @Primeragandang