Introduction

On 17 September, al-Qaeda-affiliated Malian terror group Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) carried out a series of attacks in the country’s capital of Bamako, targeting a military police training camp and the Modibo Keita International Airport. One anonymous security source claimed that 77 people died in these attacks, with 255 more wounded. These attacks come as part of the group’s broader efforts to supplant established state authority in favour of its extreme interpretation of Islamic Law. JNIM’s threat to Mali and the Sahel region at large continues to rise, with a 2023 study by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies concluding that JNIM was responsible for most of the 50% spike in fatalities attributed to Islamist groups in Somalia and the Sahel compared to the previous year.

Much of this threat stems from JNIM’s direct and indirect leveraging of digital technologies, including an extensive online propaganda campaign and potential partnering with Chinese criminal groups to indirectly sell smuggled Malian rosewood. This Insight will examine JNIM’s online media presence and its use of illicit rosewood marketing online, which may contribute to funding its regional operations.

Online Propaganda Campaign

JNIM emerged in March of 2017, the result of a merger between four Malian terror groups: the regional branch of al-Qaeda of the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), the Macina Liberation Front, al-Mourabitoun, and Ansar Dine. The latter of these groups had already developed an extensive online presence, devoting 44% of its total communications to news management, targeting Muslims abroad and drawing them into the Malian conflict as stakeholders. However, because the US State Department designated Ansar Dine as a foreign terrorist organisation in 2013, the group was limited in accessing social media platforms such as YouTube, instead relying heavily on Telegram channels to spread its communications, which became increasingly professionalised and regular. When Ansar Dine merged into JNIM, it gained access to al-Qaeda’s assets and narratives, allowing for its messaging to spread further.

JNIM operates multiple telegram channels through its media wing, al-Zallaqa. According to Héni Nsaibia and Rida Lyammouri, al-Zallaqa temporarily creates or maintains closed Telegram accounts to spread propaganda across a designated network, disseminating it to supporters and subscribers. Although periodic crackdowns have caused al-Zallaqa to temporarily migrate to platforms outside Telegram, its strategy remains resilient, with the group releasing an audio address to recruit new members on Telegram and Chirpwire on 15 August. A recent investigation found that JNIM regularly releases content, such as claiming attacks, on its Telegram, sometimes on a daily basis, and that this content includes documentary-style videos that mimic news broadcasts.

Under al-Qaeda’s umbrella, JNIM has partnered with Nigeria-based Ansaru to disseminate propaganda, radicalise members, and connect with similar organisations in other regions using Telegram accounts and chat rooms such as Rocket Chat and Element. Moreover, by leveraging its al-Qaeda affiliation, JNIM propaganda reaches broader audiences through the umbrella organisation’s global channels. For example, JNIM content reached Turkish audiences through an al-Qaeda-affiliated Turkish Telegram channel in 2018.

Inside the Rosewood Smuggling Industry

JNIM partly fuels its ongoing expansion by offering protection services to illicit rosewood smugglers in southern Mali. Between 2017 and 2022, China imported an estimated $220 million of rosewood from Mali alone. Rosewood is particularly prized in the Chinese market, where consumer demand for expensive replicas of Ming and Qing dynasty furniture made from the wood has been in high demand for decades. Ecological concerns, among others, caused Mali to ban rosewood exports in 2020, with other countries in the region following suit, including Senegal and Gambia in 2022. However, these bans have done little to stop JNIM and others from participating in this lucrative revenue source, with JNIM reportedly dislodging bandits who steal from smuggling rings more effectively than hired security agents. According to local reports, JNIM often kills those bandits who do not conform to its dictates.

China’s insatiable demand for rosewood resulted in the depletion of Southeast Asian rosewood forests around 2010, causing Chinese traders to turn increasingly to Africa. For this reason, several Chinese criminal syndicates operating in Mali and neighbouring Senegal engage heavily in the illicit rosewood trade in collusion with local authorities and businesses. According to Organized Crime Index, Chinese companies smuggle rosewood out of Mali using authorised wood export companies, with the illicit rosewood trade linked to ivory smuggling operations as well. Although locals in southern Mali allege that Chinese traders pay protection fees to JNIM, the extent of relations between the two remains unclear. However, recent clashes between JNIM and the Malian government reveal that the terror group extensively uses Chinese-made weapons, including rocket-propelled grenades with anti-tank projectiles. For these reasons, the relationship between JNIM’s rosewood protection racket and West Africa-based Chinese criminal syndicates requires further investigation.

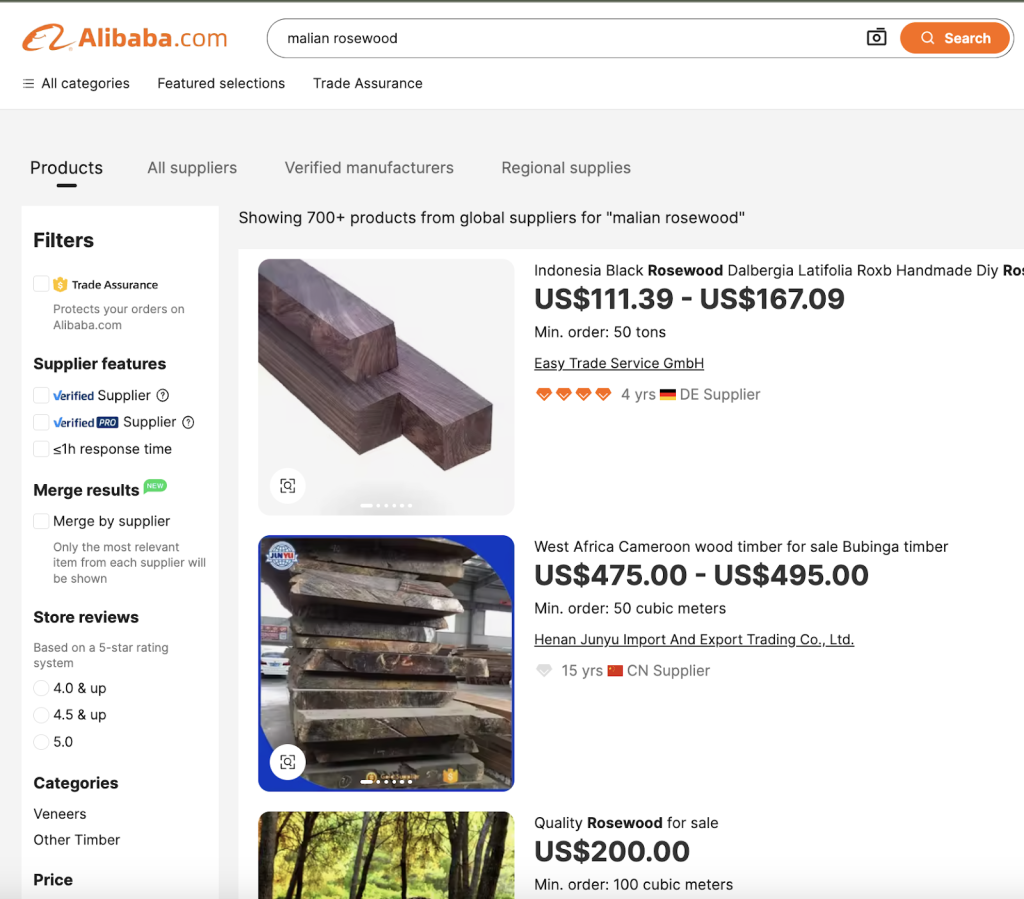

Furthermore, China’s tech sector plays a vital role in selling and marketing illegal West African rosewood, which helps fuel JNIM’s rapid expansion there. Moreover, the sector makes little effort to hide its role. A simple search on Baidu, China’s top search engine, of ‘Malian Rosewood’ (红木马里) reveals dozens of related links to online retailers and articles extolling the benefits of Malian rosewood furniture (figure 1). Although e-commerce sites focused solely on the domestic market, such as Taobao, specifically market Malian rosewood and goods made from it, on Alibaba, the country’s largest international e-commerce retailer, vendors do not list the national origin of their rosewood items, or claim it comes from markets where rosewood exports remain legal, such as India and South Africa (figure 2). In this way, it remains unclear if Chinese retailers are marketing illegal Malian rosewood that helps fund JNIM’s ongoing insurgency to the global market.

Figure 1: A Baidu search of ‘Malian Rosewood’ (红木马里) reveals dozens of related links to online retailers and articles extolling the benefits of Malian rosewood furniture

Figure 2: Although Chinese online retailers market illegal Malian rosewood to the domestic market, they do not do so on international ecommerce platforms, such as Alibaba.

Recommendations

Authorities have struggled to contain extremist content from JNIM, the broader al-Qaeda network, and other terror groups on Telegram for some time. Although the Dubai-based company recently hired around 100 contractors to work as content moderators, with just 60 full-time employees, Telegram reportedly ignores most requests for assistance from global law enforcement agencies. However, Apple and Google, which have significant leverage over Telegram due to their ability to expel it from their app stores, have successfully pushed the company to restrict the spread of extremist content on its platform. This leverage, combined with the recent arrest of CEO Pavel Durov, could push Telegram to adopt more robust measures to counter extremist content like those of other platforms such as YouTube and Instagram. Given JNIM’s resilience in using the app to spread its messaging to date, these enhanced moderation measures are likely necessary to counter its presence on the platform moving forward. Similarly, authorities should work in conjunction with Apple and Google to demand similar moderation practices at smaller chat services such as Chirpwire, Rocket Chat, and Element.

Governments and industry should do more to counter the global trade of illicit West African rosewood on Chinese e-commerce platforms. Although Western shipping companies Maersk and CMA-CGM have already committed to blocking and investigating their role in the illicit rosewood trade, respectively, this has not yet stopped smuggled rosewood from reaching China’s shores. Although international institutions can do little about the marketing of illicit rosewood inside China, customs agencies and law enforcement should more closely scrutinise the international sale of rosewood products on Chinese e-commerce platforms as these may be indirectly funding JNIM’s ongoing expansion. Finally, further investigation is needed into Mali’s illicit rosewood trade, including the local supply chains that may link Chinese smuggling syndicates and consumer markets to JNIM’s ongoing expansion.