Introduction

In the wake of the 7 October attack and the war that has followed, Hamas, the Palestinian Islamic resistance movement, has conducted much of its financial activity through established and emerging online financial platforms (OFPs) to support its rule in the Gaza Strip. Even though Hamas is designated as a terror organisation (and is therefore sanctioned) in the US, UK, EU and elsewhere, it has been able to take advantage of compliance-related loopholes and poor counter-terror financing (CTF) practices OFPs suffer from. Some of the OFPs Hamas uses and abuses include technologies such as online payment processors, virtual assets service providers (VASPs), online gaming platforms, marketplaces and social media platforms.

This Insight will analyse Hamas’ use of these OFPs, address two major misconceptions about terror financing, and illustrate how Hamas targets and abuses certain platforms by operating semi-sophisticated financial mechanisms (meaning manually operated technologies rather than fully automated mechanisms). It will conclude with recommendations on the strategic and tactical levels that, if implemented, will dramatically challenge terror financing in general – and Hamas’ financial operations in particular – while also serving the OFPs’ interests.

How Much Does Terrorism Cost?

The notion that terrorism is a low cost endeveour, which is echoed across the financial industry from time to time, is a huge misconception about terrorism and terror financing.¹ While there is some merit to this claim in relation to the cost of terror attacks when terror organisations control territory, like Hamas did in the Gaza Strip (and still does, to an extent), the cost of terrorism is extremely high.

We can break down the costs of terrorism into two criteria: attacks and control. By and large, it is true that terror attacks do not necessarily cost much. However, it depends on the type of attack. Lone-wolf and low-sophistication attacks can be carried out with minimal costs, while highly-sophisticated attacks, such as 9/11 or the 7 October attack, could cost upwards of one million USD. While low-sophistication, low-cost attacks can be executed under favourable and unfavourable conditions – such as control of territory, people and infrastructure, or lack thereof – highly-sophisticated attacks are much more likely to be carried out when the aggressor controls these resources. Hamas provides the perfect case study to support this argument. It operates with low sophistication in the West Bank, where it is not the ruling party and where Israel and the Palestinian Authority often thwart its attacks. Its relatively more sophisticated attacks originate in the Gaza Strip, where it has been ruling since 2007 and where it controls the population, the infrastructure and the economy. In other words, even if terror organisations have the funds to carry out sophisticated attacks, a lack of control over territory, people, infrastructure and financial mechanisms will likely prevent them from executing their plans. For instance, Hamas likely would not have conducted the 7 October attack without its complex and expensive underground tunnel infrastructure, where many hostages are reportedly held. Hamas could not have built the tunnels had it not controlled the territory.

The second criterion is the cost of controlling territory and people as a terror organisation.

The cost of maintaining control includes expenditure on governance (institutions and salaries), social services (education, energy, health, maintenance), security (police, military and other security services) – and much more. For context, I argue that Hamas’ annual budget is anywhere between one and three billion USD, where the main sources of income pre-7 October were from states (namely Iran and Qatar); taxes (from Gazans and businesses within the Gaza Strip, as well as tax money it received from the Palestinian Authority); from commerce the organisation conducts in the Gaza Strip (these days it makes profits from selling food at exorbitant rates); from charities; and from its investment portfolio.² We can conclude, then, that even if the cost of a complex terror attack is not necessarily high, in order to execute such an attack, a fully developed infrastructure needs to be in place, and that infrastructure is extremely expensive. Without such conditions, terror organisations cannot execute large-scale terror attacks. The cost of organisational terrorism, therefore, is fairly high.

How Hamas Uses OFPs

In their efforts to generate large amounts of money, terror organisations and their financiers have been abusing OFPs for some time now. In recent years, Hamas has taken advantage of compliance-related loopholes and poor CTF practices OFPs suffer from, and has been able to raise, move, launder and obscure funds with only minor setbacks in the process.

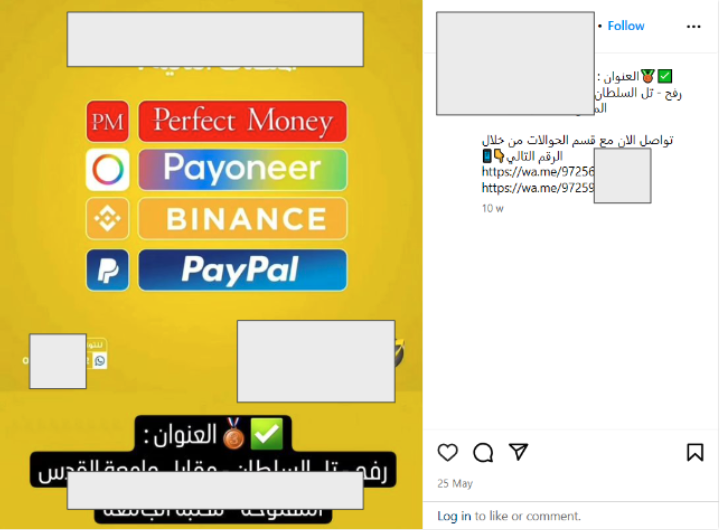

One major compliance-related loophole is the failure of sanctions-screening providers to retrieve data from the Israeli sanctions list, which – according to local regulations – must be screened by OFPs that operate in Israel. This failure allows sanctioned individuals to continue operating on numerous OFPs. Figure 1 shows an Instagram post by a Hamas-affiliated individual who was designated by Israel and whose business, a foreign currency exchange (forex) broker, was designated by the US (OFAC). He advertises several online payment companies his business allegedly keeps operating through – despite being designated and sanctioned.

The fact that Binance, the world’s leading crypto exchange, is being used by this forex broker indicates that Hamas still uses crypto assets as a financial tool. Back in 2019, Hamas began raising funds via cryptocurrencies (specifically Bitcoin), yet in April 2023, the organisation declared that it suspended its Bitcoin crowdfunding efforts to protect its financial supporters. This was due to Israel’s Ministry of Defense seizing funds from the addresses that sent Hamas cryptoassets, which was possible due to the fact that while blockchain addresses are anonymous, the payment history of each address is largely available through blockchain analysis. Nonetheless, as can be implied from the Instagram post, Hamas continues to use cryptocurrencies, which is where the forex brokers come into the picture.

Hamas operates and abuses forex brokers in order to launder funds, earn from the businesses’ profits, sell cryptocurrencies it raised through crowdfunding, and move funds through OFPs. The forex brokers themselves, regardless of whether they are owned or simply taxed by Hamas, depend on legitimate activity by ordinary people, and therefore, they publicise their activity on various platforms. This makes their social media accounts an excellent source of intelligence. Figure 2 is a Facebook post by a forex broker that is part of the same network in Figure 1. It lists a wide array of OFPs through which the business sends and receives money, including the social media platform TikTok. Other OFPs that are being used by forex brokers include marketplaces, online gaming platforms (where in-game currencies are being traded) and live streaming platforms.

Aside from the notion that terrorism does not cost much, another misconception – or rather, misconceptualisation – about terror financing is the aggregation of anti-money laundering (AML) and CTF regulations and practices. It must be acknowledged that money laundering is only one typology of terror financing, and the latter can take place regardless of the former. However, all CTF regulations and practices are part of the AML/CTF package. One is left to conclude that the lack of specific CTF regulations and practices is either due to a lack of understanding of terror financing – or simply negligence. One way or another, poor CTF controls, or lack of specific CTF controls altogether, allow terror financiers to abuse OFPs.

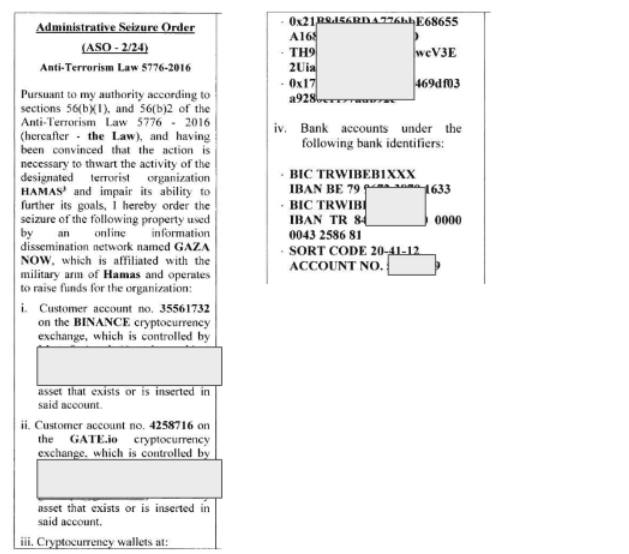

One example of such activity is crowdfunding for charities. Funds that are raised through crowdfunding can be legitimate, and the charity organisation can then distribute the funds legally, in the form of salaries, for example, without laundering any funds at all. In some cases, however, the charity’s employees also act as members of a terror organisation or are involved in terror-affiliated activities. Therefore, while the money flow is simple and direct – and does not include money laundering – it essentially finances terrorism. It is not surprising, then, that crowdfunding for charities is a major challenge for OFPs, as it has become an alternative route for generating funds through taxation following Hamas’ loss of territory. Crowdfunding is done via cryptocurrencies, online payment services and even via traditional banks, such as Barclays (see Israel’s designation of the Gaza Now campaign in Figure 3). While the amounts cannot be determined with certainty, we can estimate that millions of USD have been channelled through OFPs to charities that are either owned by Hamas or are taxed by the organisation.³

Aside from the various legal ways Hamas has used OFPs to raise and move funds, its financiers continue to launder money in their efforts to support the organisation. One such mechanism is the laundering of illicit funds through marketplaces, especially those that offer online services (such as translation, editing and tutoring), as it is difficult to determine whether such services were delivered or not. The freelancers use their marketplace account – which is linked to an online payment processor – to launder funds for terror financiers, often on a large scale, by receiving funds without providing service and then sending funds to another freelancer, who also does not provide any services. Eventually, the funds are sent to the terror financiers’ freelancer account, shell company or forex business. While these semi-sophisticated mechanisms are hard to dismantle or prevent in the first place, there are steps OFPs can take to counter terror financing on their platforms.

Recommendations

Online payment processors (including credit card companies), VASPs, marketplaces, mainstream social media platforms and other OFPs must be aware of the threat terror financing poses to the stability of economies, countries, regions and, ultimately, the world. The 7 October attack, the ongoing war that has followed, and the increasingly perilous situation in the Middle East demonstrates this precisely. Furthermore, while terror-related funds only account for a small percentage of all the funds OFPs manage – and therefore, they account for only a small percentage of the revenues – they are the root cause of many of the severe fines and negative reputation they bring to OFPs. It can be argued, then, that it is in the OFPs’ interest to tackle this issue and stop riding their luck. To that end, there are several strategic and practical steps OFPs can take.

On the strategic level, OFPs must differentiate between AML and CTF practices, regardless of the regulations. Investigations by law enforcement agencies take place not vis-a-vis regulation but vis-a-vis criminal activity. If the local authorities (and investigative journalists) identify terror financing on a platform, they will open an investigation regardless of whether the company is compliant or not. The reputational damage from such an investigation and its findings have the potential to cause a public outcry and lead to unexpected financial losses (from boycotts, vandalism and commercial disaffiliation). Such investigations can also lead to a regulatory audit, which might bear heavy fines and even personal implications.⁴ It is highly recommended, then, that OFPs tackle terror financing on their platforms as an independent phenomenon.

On the practical level, OFPs should familiarise their teams with terror financing trends, patterns and other practices that can prevent such activity from taking place and, most importantly, can prevent OFPs from receiving fines. Aside from “training” employees on terror financing beyond the periodic elementary internal training course, it is advised that OFPs use existing knowledge and capabilities that professional CTF solution providers can provide. These include databases on terror-related entities and individuals, transaction monitoring – not only in the context of money laundering – holistic CTF controls, strategisation and much more. At the most basic level, OFPs must make sure all the regulatory requirements are met wherever the company is operating.

The failure to meet Israel’s requirement to screen against its sanctions lists is a clear violation of local regulations, and, as shown in this Insight, Hamas has taken advantage of such compliance-related loopholes and poor CTF practices. OFPs, being for-profit organisations, must keep in mind that it costs less to comply than to be non-compliant. In this context, they should consider their expenses on CTF practices as investments rather than losses. Perhaps this will motivate them to take action, if not the lives and well-being of ordinary people, many of whom are their clients and even employees.

Endnotes

- During a recent book launch event in London, an executive in the online gaming industry stated that since terrorism does not require much money, terror financiers do not need to “smurf” payments, and that there is not much the financial system can do to prevent terror financing. Both assertions are wrong.

- While Iran provided approximately 100 million USD per year to Hamas, Qatar transferred to Hamas every month some 30 million USD, in cash, and provided hundreds of millions of USD-worth infrastructure in the Gaza Strip (such as building the Hamed neighborhood), as well as undisclosed amount that went directly to the Hamas’ military wing, the Izz ad-Din al-Qasam Brigades. The taxes Hamas raised when it controlled the Gaza Strip are estimated at 480 million USD per year, and the Palestinian Authority transferred another one billion USD to the Gaza Strip for salaries of public service-providers, which happen to largely be Hamas personnel. Other sources of income, such as charities, revenues yielding from the 500-million-USD-worth investment portfolio, and funds the organisation launders through shell companies, foreign currency exchange and more, can amount to hundreds of millions of USD, if not more.

- This crowdfunding page alone raised more than five million USD at the time of writing. While the charities listed in this page are not necessarily owned by Hamas, it is safe to claim that Hamas taxes charities that bring money into the Gaza Strip.

- See the Binance case, where the company was fined over four billion USD and its CEO serves time in prison.

Omri Brinner is a counter terror financing (CTF) consultant with a proven record in identifying, mitigating and preventing terror financing activity. He provides a wide array of CTF services, such as investigations, training, mapping terror financing networks, lecturing, researching and publishing. He is a Research Fellow at ITSS Verona and is an expert on terror financing and Middle Eastern geopolitics.