Content warning: This Insight contains mentions of sexual and graphic violence, suicide, and racist language

In the past few years, incels (involuntary celibates) have piqued the interest of academics, policymakers and media alike due to their association with violent attacks, including in the US and Canada, and the 2021 Plymouth attack in the UK. Incels are an online community that views society as structured along the lines of attractiveness that favour women and conventionally attractive men, thereby excluding unattractive men from heteronormative relationships. Misogynistic incels subscribe to the blackpill ideology, which asserts that attractiveness is genetically pre-determined. This leads to the belief that unattractive men are destined for continual rejection by women, condemning them to a perpetual state of despair. Retaliating against this perceived injustice, misogynistic incels advocate for and perpetuate harm towards women, including online trolling and harassment, gender-based hate speech, and sexual and physical violence threats.

Research on the incel subculture has predominantly focused on analysing dedicated incel-spaces. While some studies investigated the incel presence on YouTube, academic literature has largely overlooked TikTok. The misogynistic incel presence on TikTok was initially documented in 2021, and our 2023 paper was the first to investigate content produced by blackpilled incel creators on TikTok. More recently, a connection has been drawn between a TikTok trend focused on improving one’s appearance, popular among young men, and the incel community.

Based on the ethnographic observation of 30+ incel-related TikTok accounts and the examination of the textual, visual and audio components of 5 accounts and their respective 332 videos, this insight explains the tactics employed by incel content creators to circumvent moderation on TikTok, and highlights the growing presence of the misogynistic incel community on TikTok.

Incel Content on TikTok

TikTok was the leading mobile app globally in 2022, and boasts a large user base, surpassing 1.9 billion users worldwide in 2023. Notably, in the UK, Statista reports that as of 2021, 27.86% of users fall between the ages of 13 and 17, with 40.32% falling into the 18 to 24 age group. Despite TikTok’s minimum age requirement of 13, a 2022 Ofcom report revealed that over half of 3–17-year-olds in the UK are using TikTok.

The presence of misogynistic incel content on TikTok not only exposes a broader audience to the blackpill ideology but also targets a predominantly young audience. TikTok’s features such as hashtags, keyword searches, and music all contribute to the dissemination and promotion of incel content among users who may not have been previously acquainted with the ideology. This exposure fosters the popularisation and normalisation of such beliefs, posing significant concerns regarding their impact on impressionable users.

Rebranding the Incel Ideology

In 2022, the terms “incel” and “blackpill” were used to begin the online ethnographic observation. At the time of initiation, and as of the current writing, “incel” yields no search results, displaying the following message: “This phrase may be associated with hateful behavior.” (Fig.1).

Fig.1: Screenshot displaying #incel search performed on 11/10/23 and 3/04/24

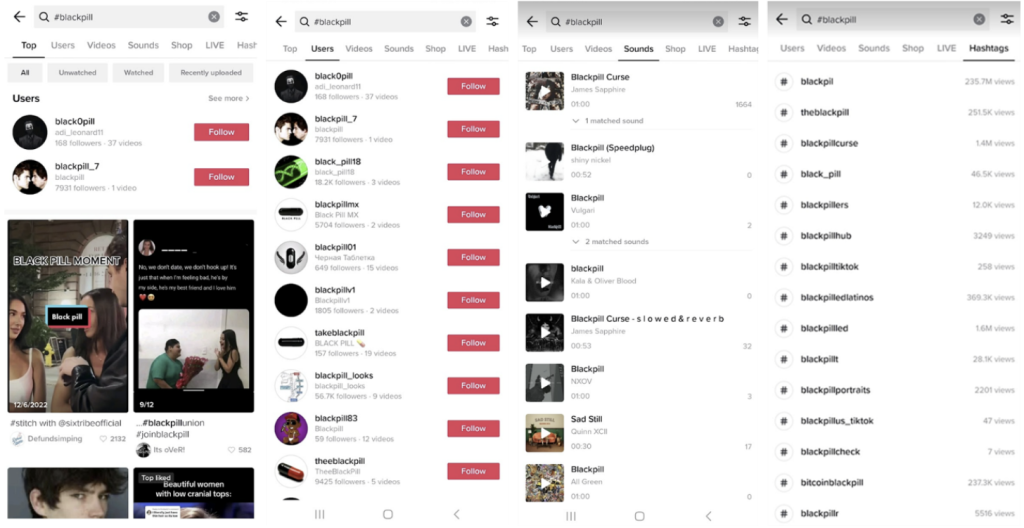

Conversely, in October 2023, when searching for “blackpill”, similar yet differently-spelled hashtags were suggested. The most popular was “blackpil”, with 235.7M views, leading to the discovery of various accounts, videos, sounds, and related hashtags promoting the blackpill ideology (Fig.2).

Fig.2: Screenshots displaying #blackpill search results for Top, Users, Sounds and Hashtags performed on 11/10/23

When searching for the term “incels”, the results included numerous videos discussing the incel ideology. However, most of the top results were counter-videos — videos created by TikTok creators and/or documentary-style videos explaining the incel ideology and warning about its association with violence and hateful misogynistic beliefs.

The ban on the term “incel” and the repurposing of “incels” for videos aimed at countering the ideology prompted misogynistic incel content creators to use variations of the term “blackpill” as account names and hashtags, to evade moderation. These adaptations include (mis)spellings such as “bxckpill,” “blackpiller,” or “bl4ckp,” and other word combinations common within the incel lexicon but less recognised outside the community. Examples include “looksmaxxing,” denoting the community’s focus on and techniques for enhancing physical appearance, and “lookism,” explaining women’s supposed emphasis on men’s physical attributes in romantic/sexual partner selection.

The data shows additional efforts to rename the incel community as “sub5s,” terminology used to refer to unattractive men, including incels.This term originates from the PSL scale, derived from three defunct incel forums (specifically Puahate, Sluthate and Lookism.net) – categorising men into PSL gods (exceptionally attractive men), Chads (generally attractive men), and Sub5s (unattractive men).

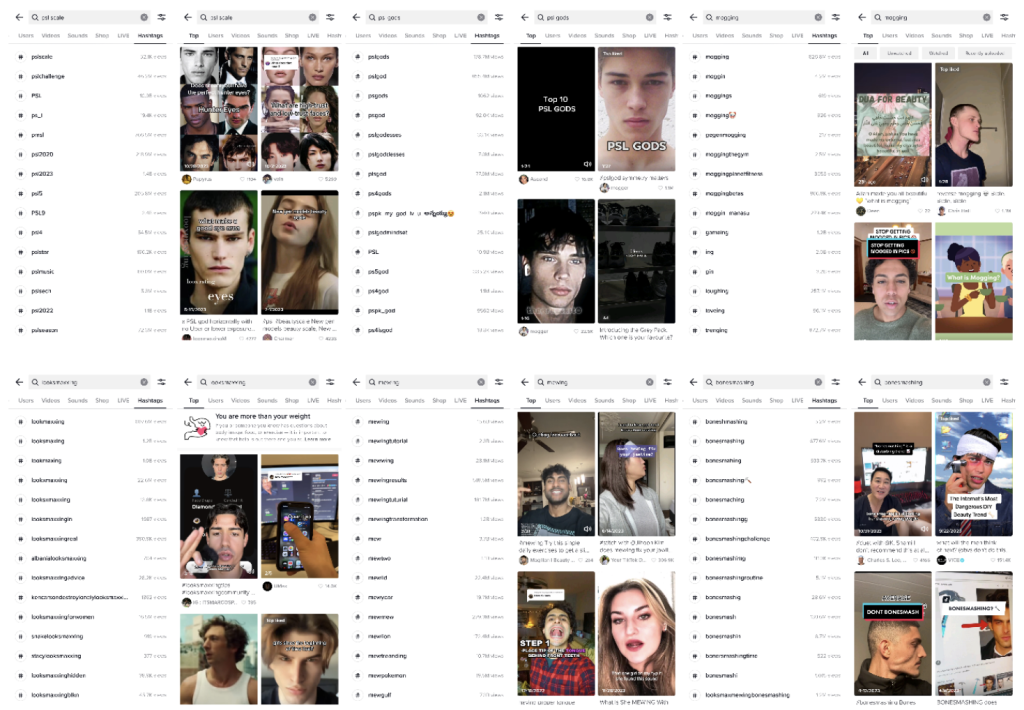

Creators’ shift away from the label “incel” on TikTok appears to stem from TikTok’s prohibition of the term and the desire to distance from the stigma associated with the name “incel,” which recently has come under warranted and increased scrutiny. Hashtags related to the PSL scale (for example, pslgods, mogging) and looksmaxxing (mewing, bonesmashing) are currently trending on TikTok, exemplifying their popularity (Fig.3).

Fig.3: Search results for three terms associated with the PSL scale and three terms associated with looksmaxxing dispalying their view numbers, and examples of recommended Top videos

This suggests that the change in name designation among misogynistic incels to alternative labels like “blackpillers” and “sub5s” serves not only to circumvent moderation but is also a concerted effort to gain popularity with new audiences, particularly other disillusioned men, dissatisfied with their appearance. This seemingly innocuous terminology might serve as an entry point for those unaware of the incel community, facilitating the revitalisation of incel ideology and its transition from niche online spaces to mainstream platforms.

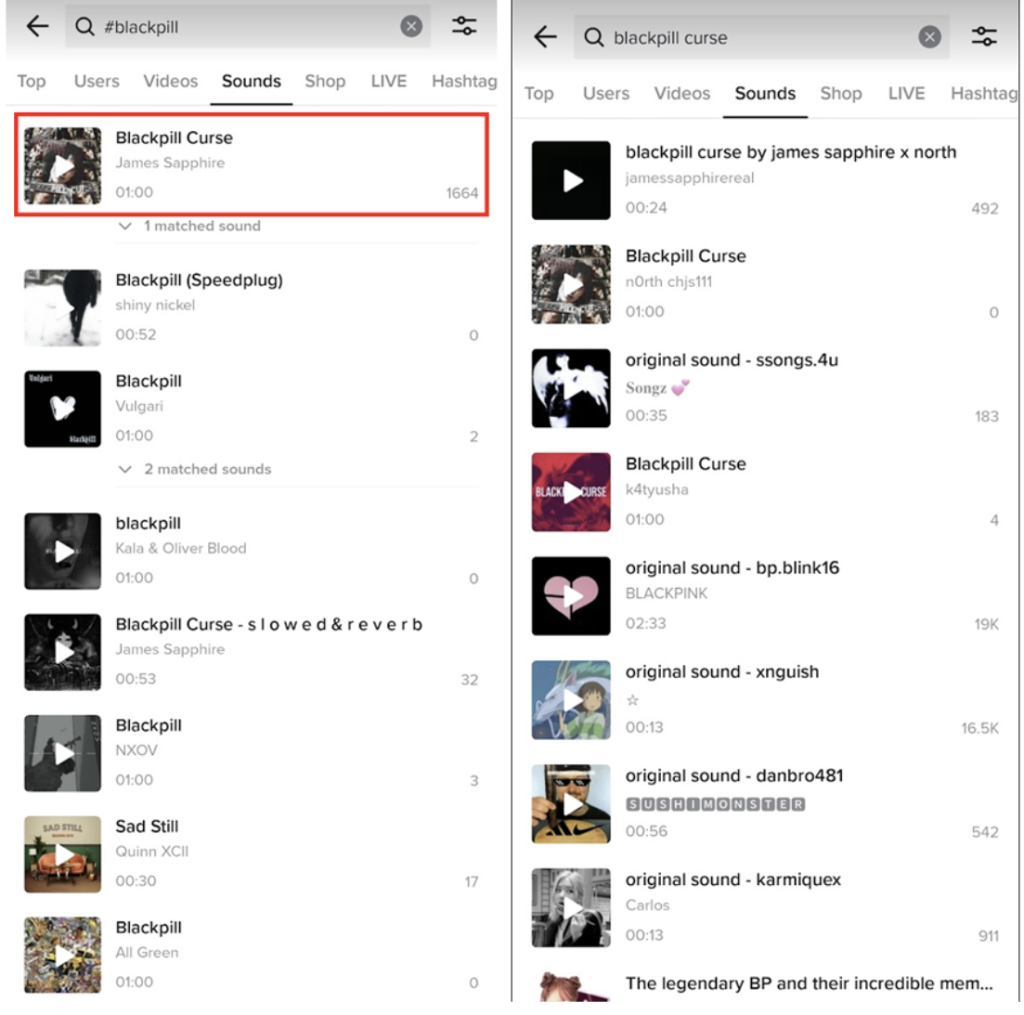

The “Blackpill Curse” song has significantly contributed to the community’s rebranding and increased visibility efforts. This song was featured in TikTok sounds (Fig.4) until early 2024 and was created by a somewhat renowned self-identified incel, who wrote, performed, and originally published it on YouTube. A condensed version surfaced on TikTok and was embraced by incel creators to label their content as blackpilled and as means of self-expression, given that the song mentions the struggles experienced by incels supposedly because of women. The song was removed from TikTok sounds in early 2024, with no clear indication whether this was at the author’s behest or due to TikTok’s recognition of the song’s implications. Nevertheless, as customary on social media, several adaptations of the original song have since been created, replacing the removed version.

Fig.4: Screenshot displaying the original “Blackpill Curse” song available on 11/10/23 and reiterations of songs available on 03/04/2024 when the original song is no longer listed

Educational Front and Scientific Disguise

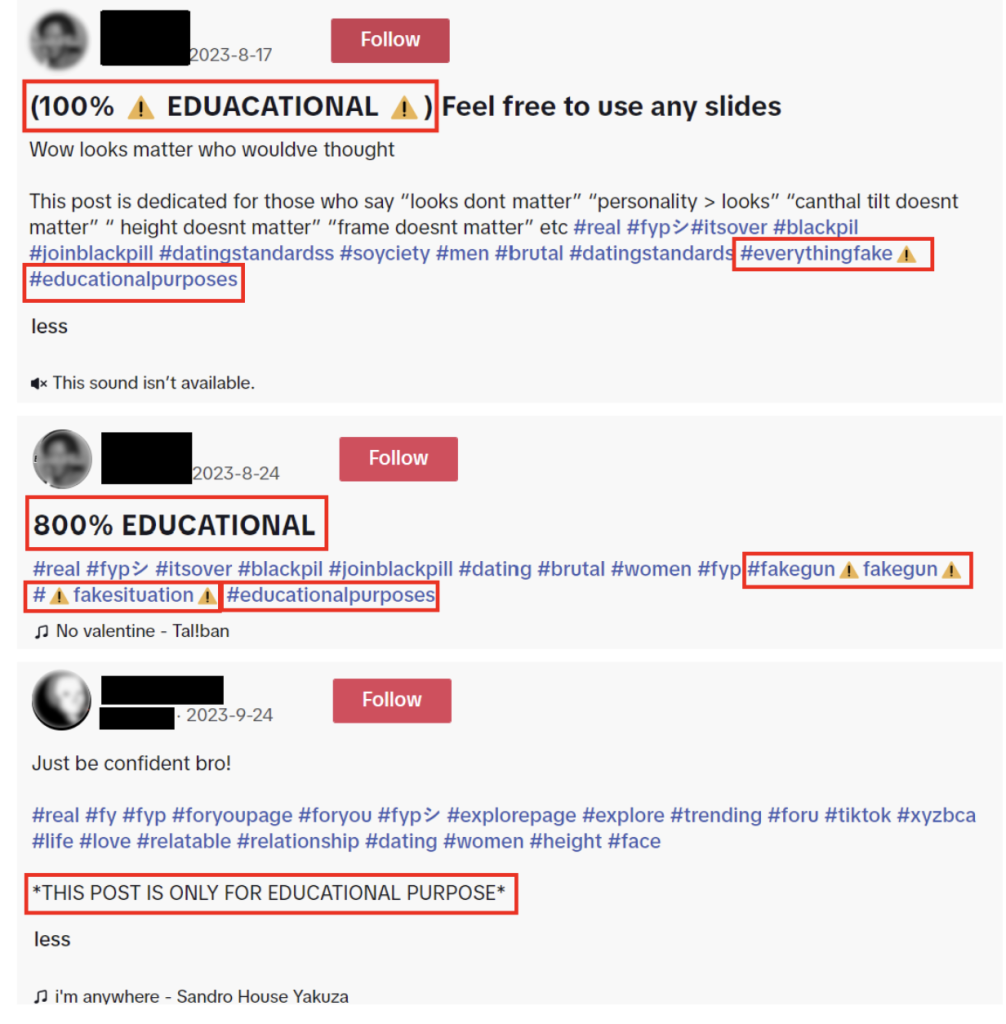

Further to the name rebranding, three out of the five incel accounts analysed used explicit educational disclaimers in their title, description and/or video content. Examples of such disclaimers are presented in Fig.5 and Fig.6.

Fig.5: ‘Educational’ disclaimers present in the title, descriptions and associated hashtags of videos

Fig.6: Disclaimer stating the images presented are ‘fake’

These disclaimers categorise content as educational or present it as ‘fake’ satirical content to evade content moderation. This strategy may stem from TikTok’s community guidelines, specifically the Enforcement section, which includes Public Interest Exceptions. According to these exceptions, certain content that would typically breach TikTok’s rules may be deemed permissible if it serves a public interest, such as informing, inspiring, or educating the community.

While the effectiveness of labelling content as educational or satire to avoid content moderation remains uncertain, it is conceivable that incel TikTok creators use these disclaimers to exploit TikTok’s exceptions. The use of pseudo-scientific data, along with the manipulation of medical and scientific literature to advance the incel ideology, may not only seek to confer legitimacy to the ideology but also play a pivotal role in enabling such content to persist on TikTok.

Visual Obfuscation of Textual and Imagery Data

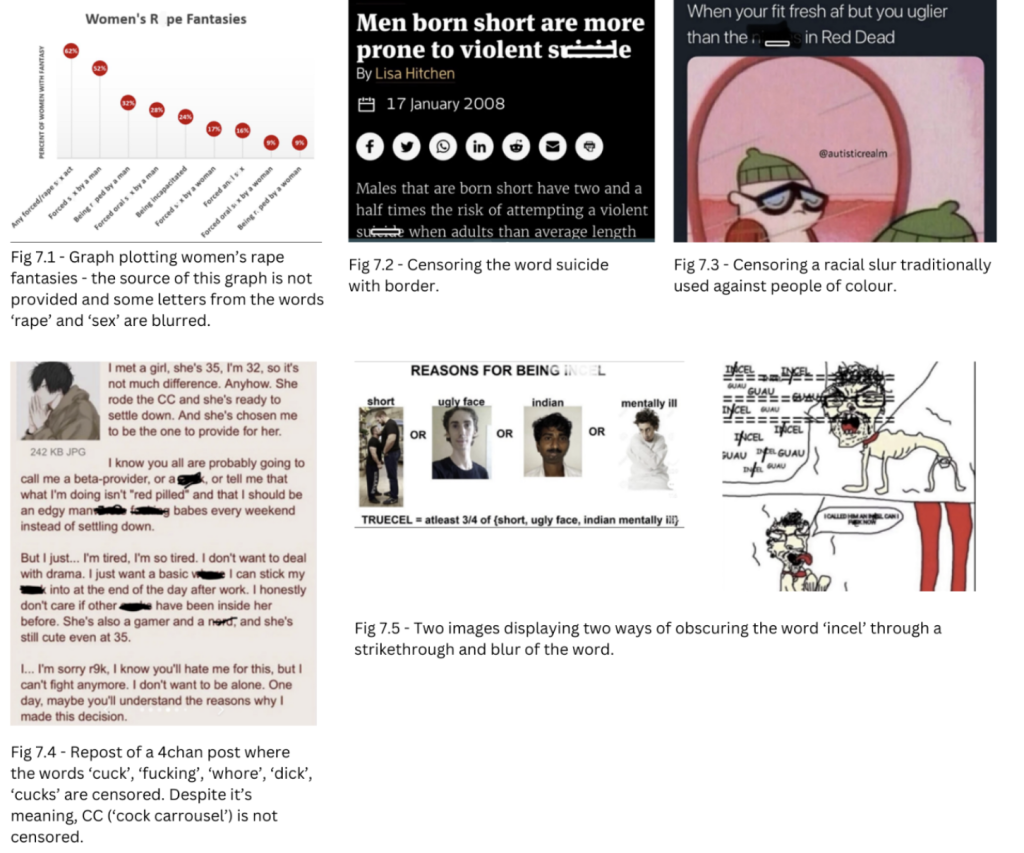

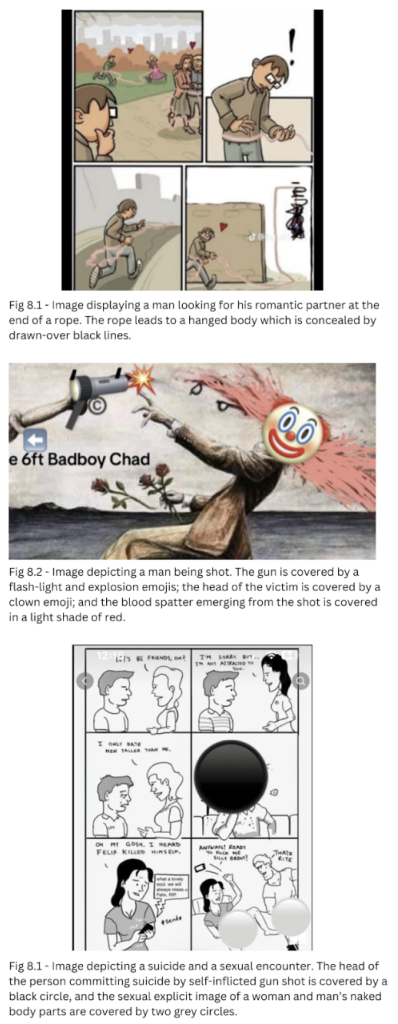

The 332 videos analysed comprise a variety of short video clips and picture slideshows. The images shown in these slideshows ranged from graphs, tables, and screen-captured media articles to typical memes prevalent within the incel community. While similar memes can be encountered on forums like 4chan, creators uploading them to TikTok often attempt to censor certain sensitive or problematic words or images. For instance, words such as “rape,” “suicide,” and “incel” are obscured with borders or blurred (Fig.7). Likewise, actions such as sexual activity, explicit sexual imagery, caricatures of women, firearms, and depictions of suicide are concealed in a similar manner (Fig.8).

Fig.7: Visual obfuscation of text examples

Fig.8: Visual obfuscation of imagery data examples

Efforts to conceal explicit or violent content are unlikely to be motivated by a desire for harm-reduction as despite these alterations, the intended message remains evident. Rather, these modifications are made to sidestep TikTok’s moderation measures and disseminate this content and associated beliefs to the masses on the platform.

However, these types of obfuscations are inconsistently applied. For example, in the above image portraying a sexual act and suicide, words such as “killed himself” and “fuck” are not hidden.

Content Moderation Challenges

More recently, and notably during the duration of this study (2022–2024), TikTok has taken measures to address the proliferation of incel content on its platform. However, these efforts have primarily focused on the inconsistent restriction of just two incel-specific terms, “incel” and “blackpill”. Restricting only two terms overlooks numerous other iterations and words from the incel lexicon, proving to be both reductive and inefficient at combating the spread of incel-related content. Particularly counterintuitive is the case of “blackpill”, where instead of redirecting users to a warning page about its hateful connotations, the search leads to alternative terms used by the community to evade moderation.

Previous research, such as Conway’s 2019 investigation of pro-jihadist accounts on Twitter, suggests that content moderation targeting specific terms played a pivotal role in de-platforming extremist groups like ISIS. However, combating less centralised forms of extremism proved more challenging with this approach. Similarly, the decentralised nature of the incel community presents difficulties in effectively moderating content, as they employ rebranding techniques and varied spellings and terminologies, in addition to visual obfuscation methods to evade detection.

Search Bar Warnings and Fact-Checking Resources

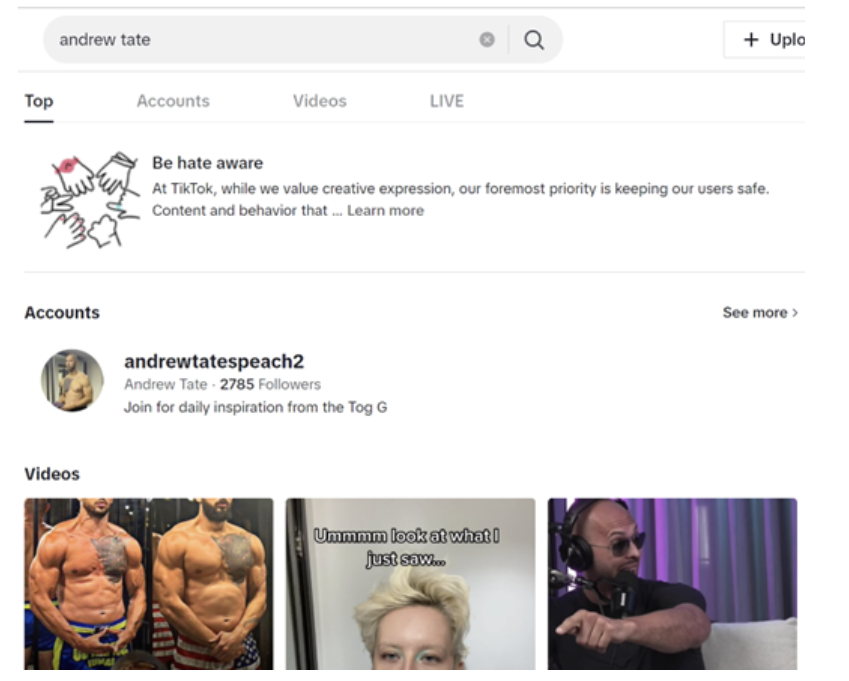

A more comprehensive approach to moderating extremist content online could involve a two-step strategy, first restricting explicit key terminology and their various iterations, and second including a search bar warning for other adjacent, mixed, or ambiguous terminology. TikTok employs a similar approach when searching for the name of the notorious misogynistic influencer Andrew Tate. Fig.9 illustrates how a warning appears when searching for his name, advising users to be “hate aware”. Instead of providing information about why he is a hate figure, users are redirected to TikTok’s Community Guidelines.

Fig.9: Andrew Tate search displaying “Be hate aware” warning

On TikTok and several other major social media platforms, information warnings, disclaimers, and fact-checks are implemented for content discussing finance, investments, and medical information. These serve to caution users that the content viewed may be inaccurate, misinformed, or potentially harmful.

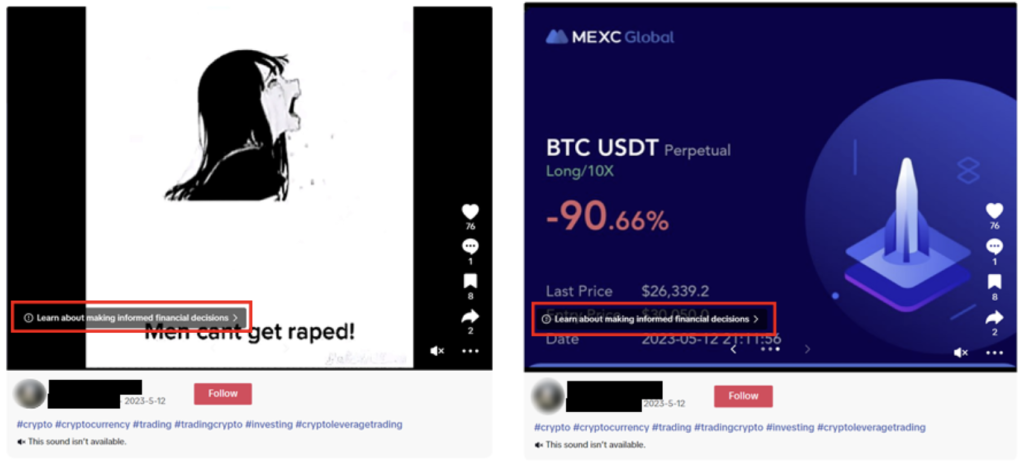

Out of the 332 videos reviewed, only one – equating women’s experiences of rape to cryptocurrency investment loss for men – contained an advisory message. This message was not aimed at countering misogyny but rather provided information about financial investment (Fig.10). This warning is part of TikTok’s initiative called #FactCheckYourFeed, launched in 2021, and focused on financial literacy. Previous research has demonstrated the effectiveness of warning labels in combating misinformation by significantly reducing belief and spread during exposure, particularly when these labels are specific, easily visible, and originate from credible sources like experts.

Fig.10: Video comprised of two images displaying a fact-checking warning for financial decisions

A prospective strategy could enhance this approach by introducing comparable warnings for searches related to misogynistic incel terminology and videos utilising linked terms or hashtags. Instead of simply redirecting users to Community Guidelines, a more effective tactic might involve directing to a dedicated page, curated by experts in the field, aimed at debunking hateful and misogynistic ideologies, encompassing not only incel ideology but also broader beliefs within the manosphere, gender stereotypes, and misogynistic tropes.

Conclusions

Misogynistic incel content on TikTok not only exposes viewers to violent and sexually explicit imagery but also fosters hatred towards women. It also significantly contributes to the ‘normiefication’ of the incel ideology – a process explaining how niche ideas and theories migrate from their original place of emergence to mainstream media, where they are exposed, explained, and potentially adopted by broader audiences.

While the negative consequences and harms of this community have been increasingly recognised in recent years, there is a pressing need for a more concerted effort in developing and implementing moderation methods to counter the spread of misogyny online and specifically for halting the proliferation of incel/blackpilled content and beliefs on TikTok.

Note. The author has solely edited the data by anonymising the names of the accounts and adding a red box around certain important aspects of the data. All other edits represent the original alterations made by the creators of the videos.

Anda Solea is a doctoral researcher at the University of Portsmouth, UK. She investigates the perpetuation and mainstreaming of extreme misogyny online, with a focus on the incel subculture. Her research primarily covers TikTok and YouTube Shorts.