Content warning: This Insight contains language describing graphic violence

Until 2002, there was no record of violent attacks in Brazilian schools. Between 2002 and 2023, the country recorded 36 violent incidents in schools, with 16 happening in 2023 alone. The 2011 shooting at a public school in Realengo, Rio de Janeiro, could be considered a terrorist attack insofar as the perpetrator had multiple targets. Besides shooting students, the attacker left a video saying that he wanted his attack to serve as a lesson for schools to tackle bullying and prevent the humiliation and discrimination of students. The 23-year-old man who killed 12 students and injured 22 people also released a manifesto with instructions for his funeral.

In a report handed to the government of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in 2022, Brazilian scholars argued that the recent spate of school shootings has some connection with the rise in extreme-right, white supremacist sentiments in Brazil, insofar as all the attacks recorded between 2002 and 2023 were perpetrated by white heterosexual men. The report also draws attention to the influence of online content on the radicalisation pathways of some of these young men. While accessing social network discussion forums, and playing online video games like Roblox, Fortnite, and Minecraft, some young Brazilians have come across extremist ideas that prompted them to take violent action, especially in schools. In three of the recorded attacks, the perpetrator demonstrated signs of radicalisation, expressing xenophobic ideas on social media and making explicit references to Nazism. In another, the perpetrator simulated the violent action in an electronic game moments before using a crossbow to go after students and teachers at a school in Espírito Santo in 2022.

Nevertheless, engagement with extremist beliefs only partially explains the recent wave of attacks in schools in Brazil, as many attacks were primarily motivated by bullying. In seven cases, bullying was pointed out by the police as the main factor that prompted the teenagers to commit acts of violence. Regardless of the motivation, violent material accessed online seems to have served as an inspiration for Brazilian youngsters to carry out violent attacks in schools.

Invited by the Brazilian non-governmental organisation Think Twice Brasil, I conducted a study to explore how social networks have contributed to a culture of violence among young Brazilians by recommending violent content. I focused on TikTok due to its growing presence in Brazil and its unique ability to produce viral videos through the hashtag #FYP (For You Page) and its auto-play function.

In this Insight, I will highlight how TikTok has recommended videos with explicit appeals to violence, drawing attention to the glorification of serial killers and terrorists and specific representations of violence that are particularly appealing to young audiences. A more detailed analysis of these patterns can be found in the full report, Algorithms, Violence, and Youth in Brazil: towards an educational model for peace and human rights.

Discrimination, Cyberbullying and Explicit Appeals to Violence

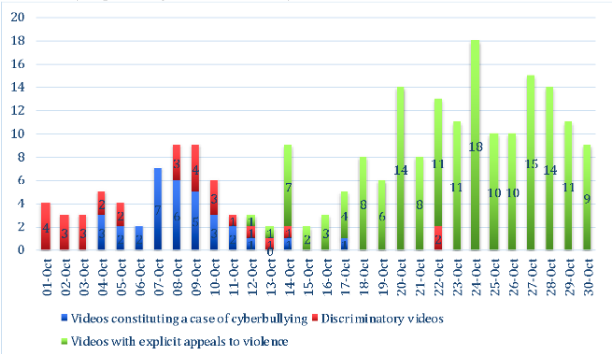

For thirty days, I mimicked the lived experience of young Brazilians who engage with the app. In the first research phase, I claimed to be interested in funny videos, entertainment, beauty, news and opinion content. Once TikTok started recommending content that aligned with my preferences, I watched all videos until the end and ‘liked’ those containing shaming, discriminatory, and explicit appeals to violence. 220 out of the 1,200 videos recommended by TikTok between 1 and 30 October 2023 promoted violence. 33 constituted a case of cyberbullying, 30 presented discriminatory content, and 157 made explicit appeals to violence, in some cases openly inciting violence in schools.

In the first days of the analysis, TikTok recommended several discriminatory videos imbued with a comic tone as if they were harmless jokes. The main victims of discrimination were Black people and women. Black people (especially men) were mainly associated with criminality. In one video, a Black man is asked about his profession, and he supposedly says “thief”. Further instances of discrimination were observed against various marginalised groups, including immigrants (mainly from China and the Middle East), members of the LGBTQIA+ community, people with autism, those with dwarfism, and, in some cases, individuals facing weight-related discrimination. It took exactly 12 days for TikTok’s algorithms to move from discriminatory videos and cyberbullying to videos containing explicit appeals to violence – in some cases encouraging youngsters to take violent action in school, as illustrated in the chart below.

Fig. 1: Videos identified promoting violence on TikTok from 01/10/2023 until 30/10/2023

Content Moderation Evasion Strategies

From 12-30 October, 157 videos recommended by TikTok made explicit appeals to violence. 115 referred to a website containing videos of people being tortured and killed (henceforth referred to as ‘PZ’). Several techniques were used to circumvent TikTok’s existing guardrails to prevent the circulation of violent content. Many videos showed individuals describing the torturing videos featured in PZ, encouraging the viewer to access them. Others used footage from the videos synced with the original sound of the victims suffering before being killed. Some used captions to describe the violent act but replaced some letters with numbers, a common moderation avoidance tactic.

Two videos used artificial intelligence models to produce deep fakes of the victims of crimes featured on PZ describing their own deaths. Fig. 2 below illustrates one of these cases, showing a woman who was violently killed in Guatemala “providing some details” about her own death. It is worth noticing that the caption features a word with a number instead of a letter. In the caption, it is written: “I was the victim of one of the most disturbing crimes in…”

Fig 2: TikTok video featuring AI-generated video of a murder victim in Guatemala describing her own death

Some TikTok users expressed pride in watching videos showing people being tortured and murdered. In this case, lack of empathy was a sign of superiority, as if those not disturbed by these videos were emotionally superior to others. This pattern was especially evident in videos challenging TikTok users to watch as many videos from the PZ website as possible. Others, however, raised concerns over their engagement with these videos, using captions to ask other users for advice on how to stop watching them.

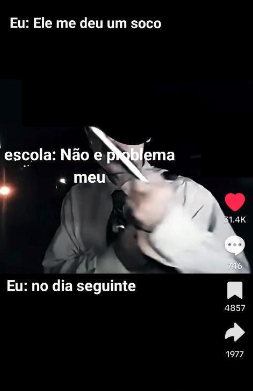

The Glorification of Serial Killers and Terrorists

Five of the 157 videos in the dataset recommended by TikTok made explicit appeals to violent action in schools. Two of them referred to PZ: one suggested that students should reproduce the videos of torture and murder available on the website in school as a form of entertainment. The other defended that the type of violence promoted on the website was a valid means of addressing bullying at school, encouraging students to torture bullies. One video used eye-catching illustrations to convey the story of a boy who killed his school bullies. A disturbing video, recommended by TikTok twice, showed a man encouraging students to bring coconut openers to school as covert weapons, now with over 30,000 ‘likes’ (Fig. 2). The caption reads: “Me: he punched me. School: it is not my problem. Me: the next day”, featuring a young man in what appears to be school uniform, brandishing a weapon.

Fig 3: Video openly encouraging students to bring weapons to school

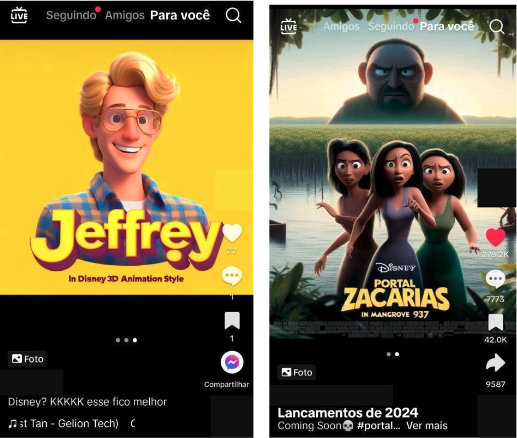

During the observed period, some of the videos recommended by TikTok that made explicit appeals to violence used some concerning techniques to target younger audiences. Counting on AI-generated models, TikTok users produced and shared Disney-like animations featuring famous serial killers as heroes and romanticising the murders featured on the PZ website. Fig. 4 below illustrates this trend. On the left, Jeffrey Dahmer, the infamous American serial killer who killed 17 people between 1978 and 1991, is presented as if he were the hero of a Disney animation movie. The figure on the right illustrates the footage of the brutal execution of three women that can be found on PZ as if it were a Disney movie poster.

Fig 4: Screenshot of videos recommended by TikTok using AI generative models to target younger audiences through Disney-like animation posters featuring serial killers and violent crimes

This trend is especially worrisome because it may contribute to the desensitisation and normalisation of violence among young people. If torture and murder are illustrated in the form of child-friendly Disney-like videos that are easily accessible on social networks, some children may start perceiving violence as a normal feature of their lives. Furthermore, as victims of violence are represented as fictional characters, they become dehumanised; their pain and deaths are transformed into a source of entertainment and divorced from reality. As AI-generated models become more accessible to a wider audience, their usage to promote violence, especially targeting young people, demands further investigation.

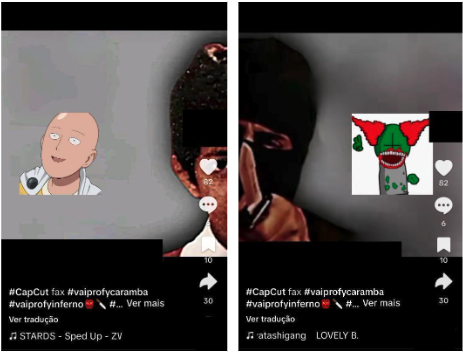

Besides glorifying serial killers, some videos glorified terrorists, conveying the idea that terrorists are like avengers seeking justice by their own means. More than once, TikTok recommended videos showing a childhood picture of Jihadi John, followed by a photo of him as a member of ISIS (Fig. 5). Jihadi John was a British citizen recruited by ISIS and became renowned for featuring in their viral videos beheading captives. The video attempts to convey the message that viewing such videos during childhood may result in individuals becoming terrorists later in life.

Fig. 5: Screenshot of a video recommended by TikTok glorifying terrorists

The Impacts of Algorithmic Recommendation

Various stakeholders can adopt numerous measures, including platforms like TikTok, the Brazilian government and schools, to mitigate the impacts of algorithmic recommendations on youth violence. TikTok, for instance, can increase investments in content moderation and facilitate easier access to the reporting process for videos that violate TikTok’s Community Guidelines. The ‘report’ button is currently hidden, making it difficult for users to report violent content. Furthermore, enhancing transparency around the processing and reporting of violent content would ensure that users and stakeholders are informed about the measures taken to address their concerns. The Brazilian government can implement an educational programme to equip young people with the knowledge and skills necessary to engage with the content they encounter online critically. As far as schools are concerned, they can adopt an educational model committed to human rights and peacebuilding.

According to UNESCO, the learning process must be transformative, empowering learners with the necessary skills to become agents of peace in their communities. Besides equipping students with digital skills and encouraging them to critically engage with online content, Brazilian schools could strengthen ties with students and their families, making them feel more included in the school community. If education is “of, by, or for experience”, interactive activities concerning peacebuilding and human rights promoted by schools and frequent dialogues between its leadership team and students may inspire them to respect other individuals regardless of their age, ethnicity, colour, ability, weight, gender, and sexuality.