Content Warning: this Insight contains images of neo-Nazi propaganda

Introduction

In a recent article for Terrorism and Political Violence, ‘White Jihad: How White Supremacists Adopt Jihadi Narratives, Aesthetics, and Tactics’, co-authored by Reichman University’s researchers Karine Nahon, Assaf Moghadam and myself, we explored the incorporation of jihadist tropes within the white supremacist movement and its potential consequences. The ideological foundations for such a collaboration can be traced back to joint efforts by Nazis and Islamists against common enemies such as the British Empire and the Jewish people.

After World War II, both sides sought revenge, leading some white supremacists to openly support jihadist terrorism if targeted the United States, Israel, or Jews. Notable figures like Ahmed Huber, Billy Roper, August Kries III, and David Myatt were known for promoting this alliance between National Socialists and Jihadists.

The implications of such cross-ideological collaborations are crucial for law enforcement agencies, counter-extremism researchers and practitioners. The online manifestation of ‘white jihad’ has become a disturbing trend, popularised by groups like National Action and the Atomwaffen Division (AWD) since 2015. This Insight summarises the findings of our article, focusing on the online dissemination of white jihad among militant extremist actors.

Conceptualising Fused Extremism

We defined white jihad as “the appropriation, utilization, or glorification by white supremacist actors of content, aesthetics, nomenclature, or action repertoires that are generally associated with Jihadi actors, or vice versa.” White jihad has been framed as the outcome of ‘cumulative extremism,’ a process in which one form of extremism provokes and magnifies another. The interaction between two opposite sides may lead to clashes, but also to the understanding that the ‘Enemy of my enemy is my friend’ – a collaboration based on shared animosity. The interactions between these white supremacists were the focus of various studies from the past few years. Some researchers emphasised the movement from one side to the other, while others explored the synergy between the two sides and their propaganda. Others have proposed terms such as ‘composite violent extremism’ to describe the fusion of extremist ideologies.

Law enforcement agencies have expressed concerns about this type of extremism and introduced new terms to describe it. In April 2021, FBI Director Christopher Wray described it as a “salad bar ideology”, referring to cases where attacks are motivated by “incoherent belief systems, combined with kind of personal grievances”. The British government has described it as “conflicted” extremism, which is also known as the Mixed, Unstable and Unclear (MUU) category. This category is used in cases “where the ideology presented involves a combination of elements from multiple ideologies,” when it “shifts between different ideologies,” or when “the individual does not present a coherent ideology yet may still be vulnerable to being drawn into terrorism.”

In our article, we argued that the term ‘fused extremism’ seems to be more appropriate. In this context, I term fused extremism to be when (1) white supremacists derive inspiration from jihadists; (2) integrate jihadi terminology and symbolism in their discourse; (3) support terrorist attacks carried by jihadists and promote their propaganda; and (4) legitimise collaboration between the two sides. The term reflects the creation of a novel type of threat that emerges from the nexus of different forms of violent extremism, rather than merely an encounter of different ideologies. Furthermore, “it presents a more descriptive explanation of who the adherents of the newly formed extremist milieu are, what they promote, and how this threat has been discernible both on and offline.” White jihad, in this context, is when white supremacists derive inspiration from jihadists; incorporate jihadi terminology in their propaganda; support jihadi terrorism; and legitimise the collaboration between the two movements.

The Convergence of Extremisms

The two movements share hatred towards Jews, the LGBTQ+ community, the United States, and Western liberal principles. They both advocate for the enforcement of strict religious rules and laws on society and in particular on women, while Islamists, including in Western countries, advocate for the establishment of the Sharia (the Islamic law) to protect Muslim women. In parallel to the calls for white jihad, some white supremacists use platforms like Telegram to call to enforce ‘White Sharia’ to protect white women. In addition, the two movements promote a sacred armed struggle against the Jews, who are blamed for being behind governments that attack traditional societies; jihadists call this the Zio-Crusader Alliance, while white supremacists call it the Zionist Occupied Government (ZOG).

This struggle is supposed to lead to a total war that will pave the way for the establishment of a new regime. Similarities between the two movements can be found also in the apocalyptic visions they share, and which they term in different ways. For example, jihadists use the term Yaum al-Qiyama to describe Judgement Day, while white supremacists often use terms such as ‘Day of Reckoning’ or ‘Day of the Rope’ – a reference from The Turner Diaries novel that has influenced many far-right extremists since the 1980s, including the Oklahoma City bomber. This vision embodies the idea that sinners or ‘traitors’ will be punished on this day of divinity and punishment.

Online Manifestations of White Jihad

Fused extremism in the form of white jihad manifests in numerous ways. One example is the adaptation of the ‘Tahwid’ (‘oneness of God’) hand gesture which reflects a Muslim’s acknowledgement of God’s oneness. This hand gesture has been used since 2015 in propaganda by National Action, AWD, and other like-minded groups from Europe, Oceania, and Latin America (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Neo-Nazis in Britain (left) and Bulgaria (right) flashing the ‘Tawhid’ hand gesture

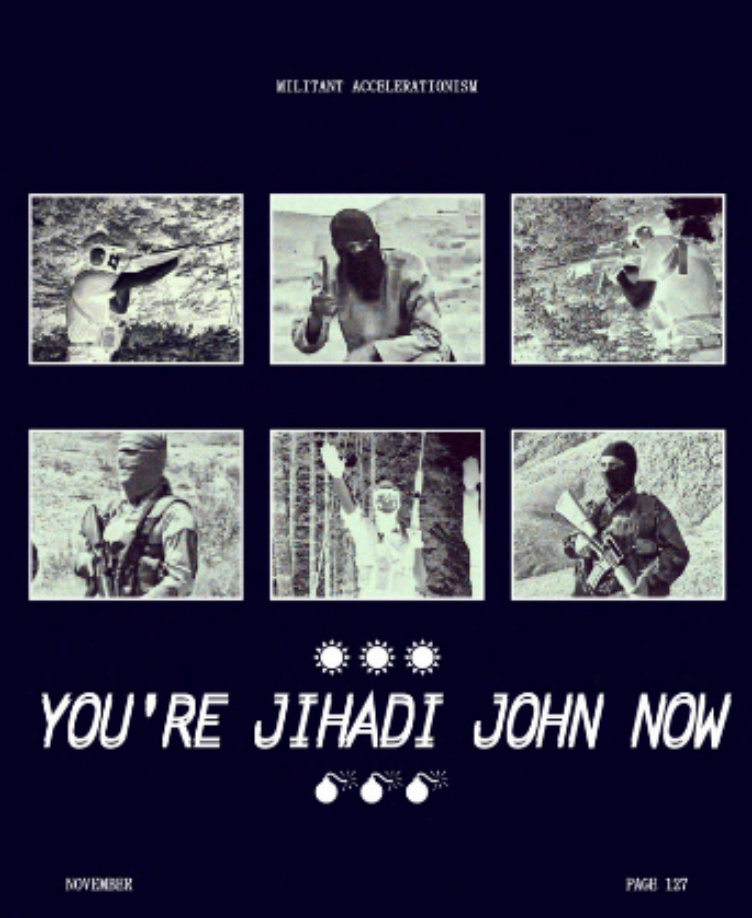

Another example can be found in the neo-Nazi accelerationist magazine Militant Accelerationism, which features a poster that reads “YOU’RE JIHADI JOHN NOW” (Fig. 2). Mohammad Emzawi, aka ‘Jihadi John,’ was the British ISIS executioner who beheaded various hostages in widely publicised propaganda videos. The same magazine also included a poster advocating for ‘martyrdom.’ Although there have not been instances of white supremacists carrying out suicide bombings in the name of martyrdom to date, the question remains – will the ideologies being discussed and promoted today be employed in the future?

Fig. 2: “You’re Jihadi John Now” from Militant Accelerationism

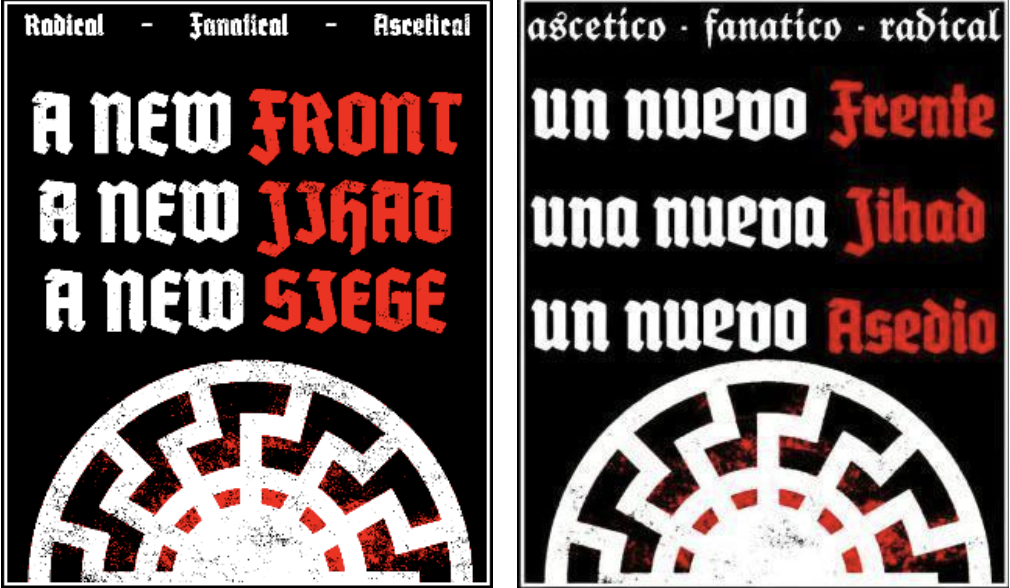

White supremacist groups such as National Action and the AWD, were the first to promote white jihad in their propaganda. For example, one of the AWD posters features an armed member and the caption “White Jihad”. Another poster published by AWD’s ideological platform Siege Culture features the motto “A New Front, A New Jihad, A New Siege” (Fig. 3). A self-proclaimed AWD cell in Argentina translated the same poster into Spanish, indicating how this rhetoric is not limited to English-speaking groups.

Fig. 3: The original AWD poster (left) and the Spanish translation by AWD Argentina (right)

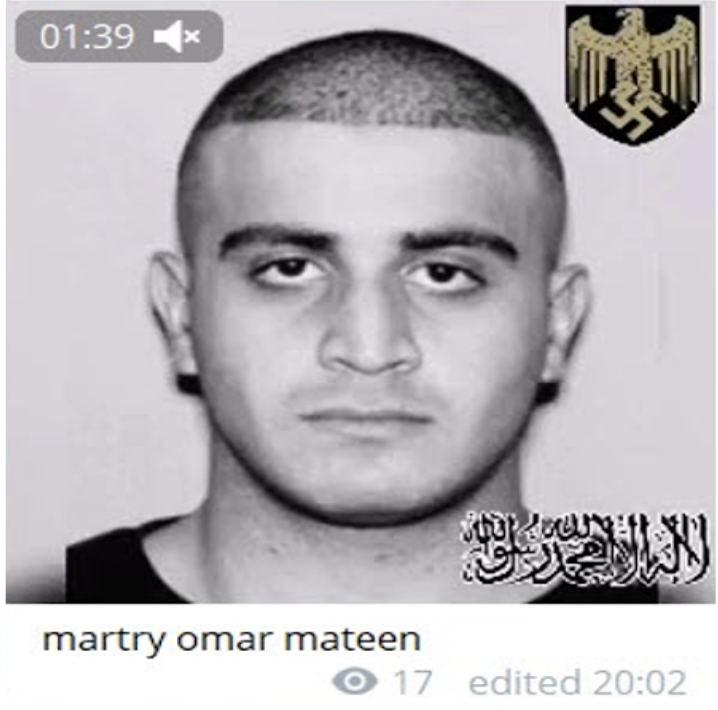

Other references to Islamic terms include ‘Peace Be Upon Him’ (PBUH), which was utilised to describe John Earnst, a white supremacist who murdered one person inside a Jewish synagogue in Poway, California in 2019; and a ‘Nazified’ version of the Islamic Shahada that, instead of the declaration that “There is no God but Allah and that Muhammed is his Prophet,” features the declaration “There is no God but Hitler and we are all his prophets.” By using the Shahada, white supremacists claim that like Prophet Muhammed, they too are messengers of God committed to eradicating God’s enemies. In addition, Jihadists who target a shared enemy are glorified, and white supremacists celebrate their attack. For example, Omar Mateen, an Islamic State supporter who attacked the Pulse Club in Orlando, a known safe space for the LGBTQ+ community, was hailed and eulogised as a ‘martyr’ by white supremacists on Telegram.

Fig. 4: Omar Mateen being called a ‘martyr’ on Telegram

Legitimising Collaboration

The idea of ‘one struggle’ against a shared enemy still ignites the imagination of some white supremacists and, accordingly, their propaganda. For example, in 2019, a now-deleted Gab account which promoted The Base, an AWD-affiliated group, shared an image of an S.S. soldier and a Jihadi, along with the caption “Inshalla we shall strike down the Zionist parasite.” In accordance with the jihad against the ‘Zio-Crusader’ alliance, the poster makes use of the term “Zionist” instead of “Jewish” – a dog whistle to the antisemitic trope that all Jews are Zionists. Another poster shared on a small Telegram channel, captioned “Brothers in Hate”, features a Klansman, a Confederate fighter, a Nazi soldier, and an Islamic State member. By sharing such posters, white supremacists normalise collaboration with jihadists and legitimise the ‘one struggle’ concept (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5: “One Struggle” (left) and “Brothers in Hate” (right)

Certain propaganda highlights this shared struggle by portraying those who fight against the Jews as sacred warriors, sharing both the fight against a common enemy and dreams of the afterlife. One poster shared on a now-deleted Telegram channel, features a ‘Nazified’ version of Jihadi John, a swastika, and the following statement: “FOLLOWERS OF THE FUHRER, FOLLOWERS OF THE PROPHET AND FOLLOWERS OF THE CROSS: WE SHARE THE SAME JIHAD, FIGHT THE SAME ENEMY, AND INHERIT THE SAME PARADISE!”.

Conclusions

Our study aimed to investigate the phenomenon of white jihad, in which white supremacists embrace jihadi narratives, motifs, aesthetics, and actions. The concept of ‘fused extremism’ was used as an analytical tool that helped us to explore four main aspects of the convergence between white supremacy and jihadism.

The white jihad phenomenon poses several challenges to tech companies responsible for content moderation. Decisions must be made according to the distributor’s categorisation (whether they are recognised as a terrorist organisation or hate group) and the content itself (determining if it incites violence or hate speech). Yet, a question arises: what should tech companies do when the distributor and the content do not necessarily relate to one another or lacks affiliation with one coherent ideology? For instance, how should they handle an account featuring a non-malicious profile picture (such as an anime character), alongside jihadi nasheeds that were not produced by a designated terrorist group, O9A-Satanist chants, and imagery inspired by the AWD? Such cases blur the boundaries between extremist ideologies and the emerging phenomenon of fused extremism, making it more challenging to make clear-cut decisions about specific content. Addressing these complexities requires further research and a deeper understanding of new and emerging trends in fused extremism.

Dr. Ariel Koch is a postdoctoral researcher and lecturer at the Lauder School of Government Diplomacy and Strategy and a fellow researcher at the International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT) at Reichman University. Dr. Koch is also the Director of Violent Extremism Research at ActiveFence, a leading Trust and Safety provider for online platforms, protecting over three billion users globally every day in over 100 languages from malicious behaviour and content, including child safety and exploitation, disinformation, hate speech, terror, nudity, fraud, and more.