Introduction

The Love Jihad conspiracy theory, primarily propagated in India, alleges that Muslim men aim to convert Hindu women through seduction, marriage, and forced conversions in order to change the population composition and erode Hindu culture. This narrative can be traced back to as early as the 1920s but has gained significant cultural and political prominence since 2007. The escalation of the influence of love jihad is evident in the recent enactment of anti-religious conversion laws by several Indian states. These laws have coincided with an increase in documented acts of violence, as tensions between religious communities have escalated.

The Love Jihad conspiracy theory shares a common element with the Great Replacement theory. Both conspiracy theories are focused on the threat of demographic change and a particular cultural or religious group. These conspiracies tap into anxieties about identity, culture, and power dynamics within society. This Insight aims to provide an overview of the relevance and significance of the Love Jihad narrative in terms of its historical context, social implications, and various strategies employed for its propagation.

Love Jihad in History

The Khilafat movement, a pan-Islamic force that arose in India in 1919 during the British Raj, symbolised unity among the Muslim community. During the same period, the Malabar rebellion (1921-1922) saw widespread resistance to British colonial rule in the Malabar region of Kerala.

The rebellion was led by a group of Muslims, who were predominantly agricultural workers against the British colonial authorities and Hindu landlords. This rebellion was marked by reports of violence against Hindus, accounts of rape, forced conversions, and abductions of Hindu women, which deepened the divide between religious communities. These events sparked a sense of urgency among Hindu reformist organisations, responding to the perceived threat of a united and militant Muslim population poised to eliminate Hinduism and its cultural heritage. Illustrating this sentiment, R. Dayalu’s poem from 1928, which was later banned, articulated concerns about schemes to increase the Muslim population through forceful conversions of women:

Muslims will never be your companions… They are making new schemes to increase their population and make people Muslims. They roam with carts in cities and villages and take away women, who are put under the veil and made Muslim. (Translated Excerpt)

Contemporary Revival of Love Jihad

There are three core events that have led to the revival of the Love Jihad conspiracy. First, themes echoing Dayalu’s poem found renewed relevance through the campaigns of the fringe organisation Hindu Janajagruti Samiti (HJS) in Karnataka and parts of Kerala, starting in 2007. The term ‘love jihad’ gained legitimacy in 2009 when the Karnataka High Court ordered an investigation into the alleged movement following a legal petition from the father of a Hindu woman, who married a Muslim man. The father claimed in the petition that she was lured by the Muslim man as part of a greater conspiracy of ‘love jihad’ where Muslim men feign love towards Hindu women to marry and convert them to Islam. The court connected the term to cases of missing women, which was further amplified through media coverage. The Supreme Court requested the National Intelligence Agency to undertake a probe into the alleged theory following a similar allegation in Kerala. Subsequent investigations found no evidence for the claims of a conspiracy by Muslim men to entrap and convert Hindu women.

Second, the Muzaffarnagar riots in 2013 were primarily triggered by allegations of stalking of a Jat girl – one of the dominant Hindu castes in India – by a Muslim man, leading to widespread anger and retaliatory violence. This incident soon evolved into a larger narrative of Love Jihad aimed at the Hindu community to increase the Muslim population. The riots resulted in the tragic loss of lives and the displacement of thousands of individuals. Once again, subsequent investigations did not find evidence to support the claims of Love Jihad that sparked the violence.

Finally, the film ‘The Kerala Story‘ premiered on 5 May 2023, claiming to depict Hindu and Christian women being lured into joining ISIS, as a fictional dramatisation of true stories. The film alleged that 32,000 women in Kerala disappeared after being enticed by Muslim men and indoctrinated into the extremist group. The film garnered support from political leaders, including Prime Minister Modi. It achieved significant box office success, earning over 560 million rupees ($6.8 million, £5.4 million) in just five days, despite a small budget and absence of major stars. Fact-checking website Altnews found no evidence to substantiate the cited figure of 32,000 women.

Impact of Love Jihad

The Love Jihad theory impacts Indian society in various ways. First, the theory aligns with the politics of fear, portraying social life as perilous and susceptible to victimisation. Consequently, the narrative fosters the belief in the necessity of protective measures against women, such as policing, intervention, and community vigilance. This perception may grant relevance, financial support, and political backing to religious and militant organisations purporting to address these concerns.

Second, opposition to the perceived predatory ‘other’ serves as a justification for acts of violence masked as protection. For instance, during the Muzaffarnagar riots, a leader justified the violence by citing the purported outrages committed by Love Jihadists against Hindu women and girls and the need for corrective action to defend the honour of the Jats against perceived aggression from Muslims.

Third, the narrative of ‘forced’ conversions diminishes female agency by constructing the Hindu female body as a battleground for community preservation, transgression, and purity. An illustrative incident occurred in late 2012 when a khap panchayat (local caste-based council) in Western Uttar Pradesh imposed a ban on women possessing mobile phones, driven by rumours that Muslim-owned mobile phone shops facilitated interactions between Hindu women and Muslim men. A leader from the khap panchayat infamously remarked that “only whores select their own partners”, reinforcing their aim to curtail female autonomy.

Spreading the Love Jihad Conspiracy Theory Online

This section explores the strategies and tactics employed in the construction and dissemination of the Love Jihad theory, both online and offline. By critically examining these strategies, this analysis sheds light on the mechanisms employed to propagate and legitimise the Love Jihad, as well as proposes future areas of research.

Text patterns and migration of claims across languages

Supporters of the Love Jihad conspiracy disseminate information using text and images that are restated word-for-word or with slight alterations, often in high volumes in a likely attempt to dominate the information space. Replicating text patterns is a well-known tactic and is observed across multiple reported global online information incidents. Given India’s language diversity, online content and media usually do not translate well. However, Love Jihad-related online content breaks this pattern with frequent translations being shared across regions.

For example, soon after the release of ‘The Kerala Story’ in May 2023, over 90 posts used the exact same language and images of alleged cases of Love Jihad on global platforms in English, Hindi, Bengali and Malayalam, with the most popular being shared over 850 times. Open-source research shows that these same claims initially surfaced in 2018 in a WhatsApp group in Malayalam, and have since migrated.

Sharing of personally identifiable information

A disturbing trend within the Love Jihad discourse is the deliberate sharing of personally identifiable information (PII). Sharing names, images, contact details, and addresses of alleged victims and perpetrators enhances the perceived credibility and authenticity of the discourse. This practice elicits emotional responses, fosters trust among readers exposed to this information online, and reinforces the notion that the claims are grounded in real events and individuals. This practice also acts as a deterrent to inter-faith relationships as this sharing reportedly leads to online harassment and offline intimidation.

Use of Memes to Suggest Adverse Consequences

Memes are frequently utilised to propagate the theory and highlight the perceived adverse outcomes of female autonomy. The strategic use of memes aligns with research indicating that their effectiveness relies on their relevance to timely events.

Fig. 1: A meme referencing the S Walker murder case

The meme depicted in Fig.1 references the S Walker murder case, in which a man killed his partner and stored her body in a refrigerator. It warns against marrying a Muslim man, implying its fatal consequences. Variations of this meme led to ‘#fridge’ being a trending topic on Twitter in 2022. Figure 1 illustrates a grid representation consisting of four quadrants. The first quadrant, labelled as “Step 1,” portrays a scenario wherein a Muslim man encounters a Hindu woman. In the second quadrant, designated as “Step 2,” the image depicts the Muslim man removing the woman’s Bindi, a decorative red dot on the forehead, which in this context symbolises her Hindu faith. The third quadrant, labelled as “Step 3,” shows the Muslim man covering the woman’s head symbolising religious conversion. Finally, in the fourth quadrant titled “Step 4,” an image of a refrigerator is presented

Fig. 2: A meme portraying the upper half of the image portrays a traditional Hindu bride, while the lower half depicts the lower body of a woman that has been confined within a suitcase

Fig. 2, titled ‘It’s all about choice’ represents an image divided into two distinct sections. The upper half of the image portrays a traditional Hindu bride, while the lower half depicts the lower body of a woman that has been confined within a suitcase. Figure 2 alludes to viral claims of Hindu women being killed for refusing to accept Islam – a phenomenon that fact-checking organisations have debunked multiple times on different occasions given the resurgence of this trope (e.g. Mathura 2022, Gurugram 2022, Uttarakhand 2022). The meme implies a choice between being a traditional Hindu bride or suffering a grisly fate, such as being stuffed in a suitcase.

Fig. 3: A meme featuring blood-splattered tombstones bearing the names of female murder victims. The accompanying sign reads ‘Love Jihad Park’

Fig. 3 portrays a blindfolded woman walking towards a man wearing a prayer cap, offering flowers while concealing a knife behind his back. The speech bubble translates to ‘Mine is not like that’, juxtaposed with blood-splattered tombstones bearing the names of female murder victims like S Walker and Tunisha Sharma. The accompanying sign reads ‘Love Jihad Park’.

Hindu Media Infrastructure

Analysing the posts under the hashtag ‘Love Jihad’ on Koo – an Indian microblogging site with over 60M users – reveals multiple online media entities which contribute heavily to the discourse and amplify each other. These entities fundraise through dedicated Non-Governmental Organisation led dharmic crowdfunding platforms set up to empower professional content creation and organisations that share advocacy for “Hindu Human Rights” (for examples, see here, here and here).

Hindu Post, another heavy contributor to the topic on Koo, is affiliated with Hindu Media Forum, a registered NGO which aims to “keep the world informed through honest reporting as well as unbiased analysis of the events taking place around the globe.” Some of Hindu Media Forum’s claims have been fact-checked by AAP Fact Check and found to be false. The dissemination of false information by NGOs on the global stage can have a detrimental impact on other Indian NGOs, limiting their effectiveness and hindering their advocacy efforts. This can occur through the erosion of trust and credibility, making it harder for Indian NGOs to carry out their work and gain support for their causes.

Offline Operations

References to rescue operations aimed at restoring alleged Love Jihad victims to their families are prevalent on digital platforms. Singhabahini, an NGO involved in such operations, gained attention for providing financial and legal support to individuals associated with anti-Muslim violence. The organisation calls for donations via Twitter, usually in conjunction with information on alleged instances of Love Jihad. The organisation is also raising funds through the crowdfunding platform Milaap to support the vulnerable Hindu community in West Bengal. Other local organisations in Uttar Pradesh such as Hindu Yuva Vahini have also been reported to engage in policing measures against Muslims.

Per reports from Intercept and India Today, such organisations typically learn about an interfaith relationship through local informants and local marriage registration offices. After a woman is found to have married a Muslim, organisations often convince her to leave them. If she refuses, they may resort to emotional blackmail, often from her parents, or threaten her and her partner with violence. In some cases, the organisation arranges for the woman to marry a Hindu man. Several of the alleged victims whose information was shared online disclose that such organisations planned to visit them in their houses — the online posts lay bare the addresses — to ‘educate’ their parents.

Role of Women in Offline Operations

Lately, the Love Jihad theory has gained traction among female influencers and female-only organisations, such as the Durga Vahini (the sister wing of Vishwa Hindu Parishad). Often, female members of these organisations have familial relations with men in their counterpart organisations. A division of Durga Vahini organised a day-long event in May 2023 with the primary objective to educate Hindu girls about the dangers of Love Jihad. Manipulated images of a popular actress who married outside Hinduism in half a niqab were used by the Durga Vahini to drive re-conversions of Hindu women who married Muslim men. Durga Vahini is also linked to riots in Bijnor as well as violent incidents in 2002.

On May 20, 2023, during a public function in the Kutch district of Gujarat, 530 women were provided with daggers for self-defence to combat Love Jihad. Influencer Kajal Hindustani, who is on bail for alleged hate speech related to inciting violent incidents, reportedly attended the event. The news coverage of the event highlighted the importance of being “prepared to teach a lesson” to those deemed as outsiders and Hindu daughters were urged to be vigilant against Love Jihad.

Conclusion

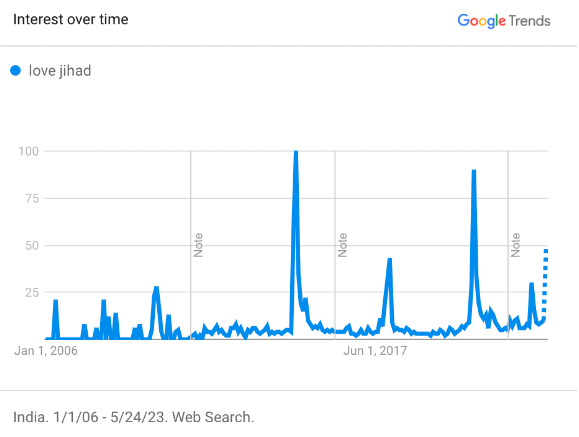

Love Jihad theory has a long history in India, and if search trend results (Fig. 4) are any indication, the narrative’s popularity is poised to keep resurfacing and growing. This implies the unfortunate prospect of more communal violence in India.

Fig. 4: Google search trends for ‘Love Jihad’ from 2006-2023

A holistic response from Indian society, as well as risk mitigation efforts from Indian and global technology platforms, may be required. The dissemination of the theory and its antecedents have involved evolving tactics from poems to memes and complex organised regional operations with access to PII and are adept at using technology to achieve their goals. Some of the proposed areas of future research include the use of technology in narratives migrating and adapting across Indic languages, a deeper dive into the funding strategies of NGOs involved at various stages of mobilisation (dissemination and enforcement operations) as well as the role and agency of women in the Love Jihad theory in South India.

Devika Shanker-Grandpierre is a seasoned risk practitioner whose expertise lies in developing actionable solutions based on interdisciplinary research that connects the dots between historical perspectives, contemporary technological advancements, and the governance strategies necessary to minimise societal harm. By drawing insights from various fields, Devika provides a holistic approach to risk management that embraces sustainable and responsible change.

Twitter: @didntmeandevice