Introduction

In recent years, a significant amount of research has paid attention to the widespread use of social media among extremist groups and how aspects of the technology operate to influence users. How and to what extent the various features and affordances of digital media platforms mould user decision-making and community building remains an important consideration when countering the spread of extremism online. Yet, little is known about how visual emojis are used in extremist communications, how they influence a user’s interpretation of extremist ideology, and how this is experienced across various countries.

In this Insight, we present condensed findings from a cross-national comparative study examining the use of Facebook’s reactions among Australian and Canadian far-right extremist groups. We adopted a mixed methods approach to assess levels of user engagement with administrator posts specific to each reaction and analysed themes and narratives which attracted the most engagement specific to 😡 ‘Angry’ and ❤️ ‘Love’. Findings are drawn from 4,605,043 reactions assigned to 97,479 administrator posts across 59 Australian and Canadian far-right groups from 2016 until 2019. We sought to understand why certain reactions appealed to these groups more than others and considered whether certain reactions characterised user decision-making when interacting with far-right themes and narratives.

More than Pretty Pictures

Before presenting the results, it is useful to explain why we chose Facebook’s reactions as the measurement of online emotion. Facebook’s reactions are design elements derived from emojis. Emojis are possibly the most popular form of digital communication in use today. They consist of a range of discreet graphics which display a multitude of non-verbal cues. In the mid-2010s, Facebook created reactions with the intention of empowering users to signal their emotions in a prompt and communal fashion. Adding to the already existing 👍 ‘Like’ button, the company introduced six emoji-based ‘reaction’ symbols (Figure. 1). Though Facebook’s reactions closely resemble and are derived from emojis, they differ in that they consist of just seven symbols, each is designed to preview a selected emotion, and they look the same across all devices that have Facebook installed.

Figure 1. features the current and most consistent set of Reactions available to users on Facebook (‘Like’, ‘Love’, ‘Thankful’, ‘Haha’, ‘Wow’, ‘Sad’, and ‘Anger’).

Even though reactions are engineered to animate and exaggerate specific sentiments, the meanings implied by their use can vary dramatically. Each storyline posted on Facebook represents a unique context and the decision to post a particular reaction in response is shaped by the viewer’s cultural, social, and political beliefs. Though difficult to detect in a single use, when reaction usage within an online community is consistently partnered with a type of story, their usage can reveal shared community norms and values. In this way, reactions are more than simply colourful icons on the screen; they become an important mediator in online political communication and a mechanism that dictates and maintains community norms.

Reactions offer a unique behavioural metric for online emotion and help reveal the role of Facebook’s design architecture in regulating and maintaining far-right group community values and assumptions. This metric is interesting when measured against extremist groups stemming from different-yet-comparable cultural and political contexts, like Australia and Canada.

Findings

Though the full results of this study are explored in greater detail elsewhere, this section previews patterns of reaction usage in two ways:

- A macro-level quantitative assessment of the frequency and proportionate use of six reactions across three different types of far-right extremist groups (separated thematically as being predominantly either ‘anti-Muslim’, ‘cultural superiority’, or ‘racial superiority’ in orientation); and

- A micro-level qualitative assessment of the themes and narratives which attracted the most engagement pertaining to 😡 ‘Angry’ and ❤️ ‘Love’.

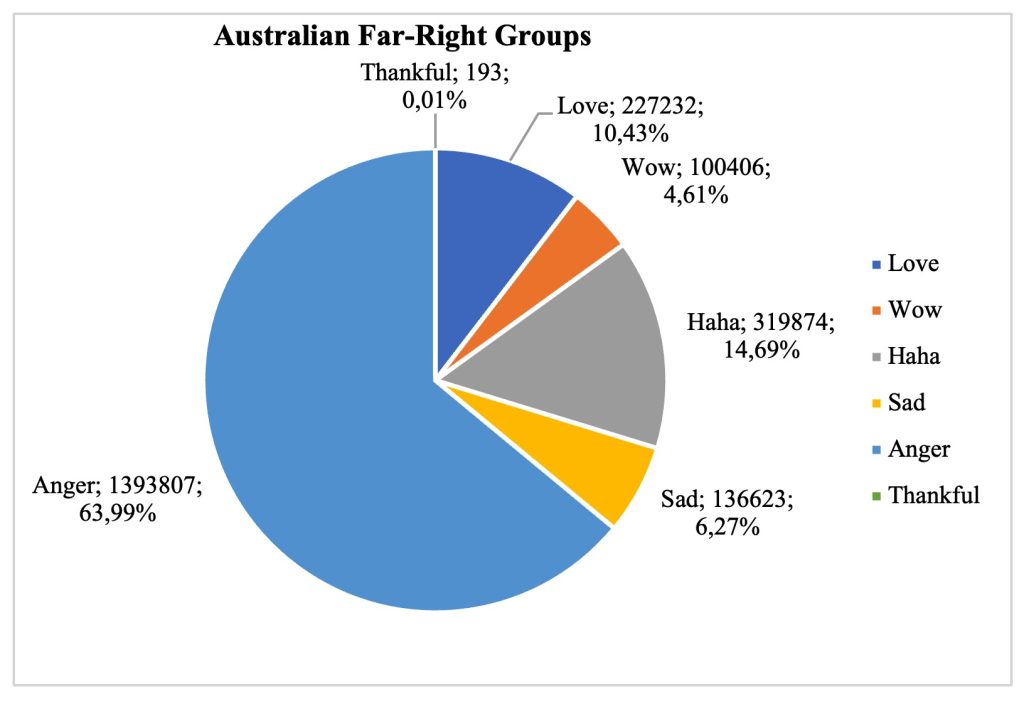

Figure 2. The frequency and proportionate use of Facebook’s reactions by users across every Australian far-right group in the sample from 2016-2019.

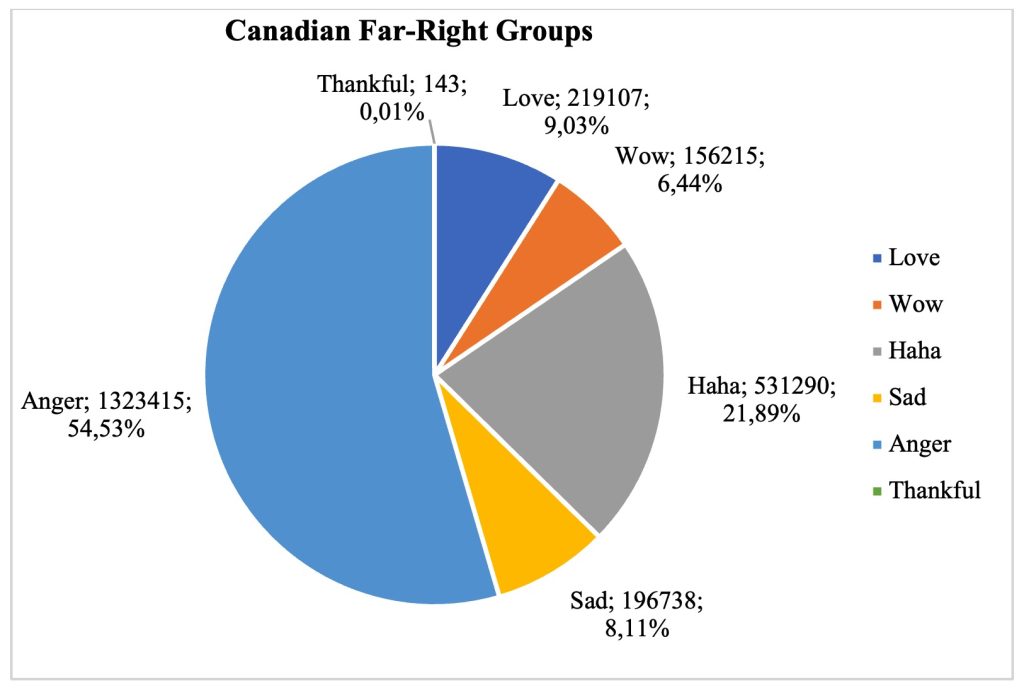

Figure 3. The frequency and proportionate use of Facebook’s reactions by users across every Canadian far-right group in the sample from 2016-2019.

Macro-Assessment

When comparing Australian and Canadian groups, users in Australia (63.99%) and Canada (54.53%) predominantly used 😡 ‘Angry’ (Figures 2 & 3). Australians used 😡 ‘Angry’ (+17.3%) and ❤️ ‘Love’ (+15.5%) at a greater percentage rate compared to their Canadian counterparts. However, Canadians made use of 😢 ‘Sad’ (+29.3%), 😂 ‘Haha’ (+49%) and 😯 ‘Wow’ (+39.7) more-so than Australian groups, while ‘Thankful’ and 😢 ‘Sad’ remained consistently at a very low percentage rate across both nation-level samples.

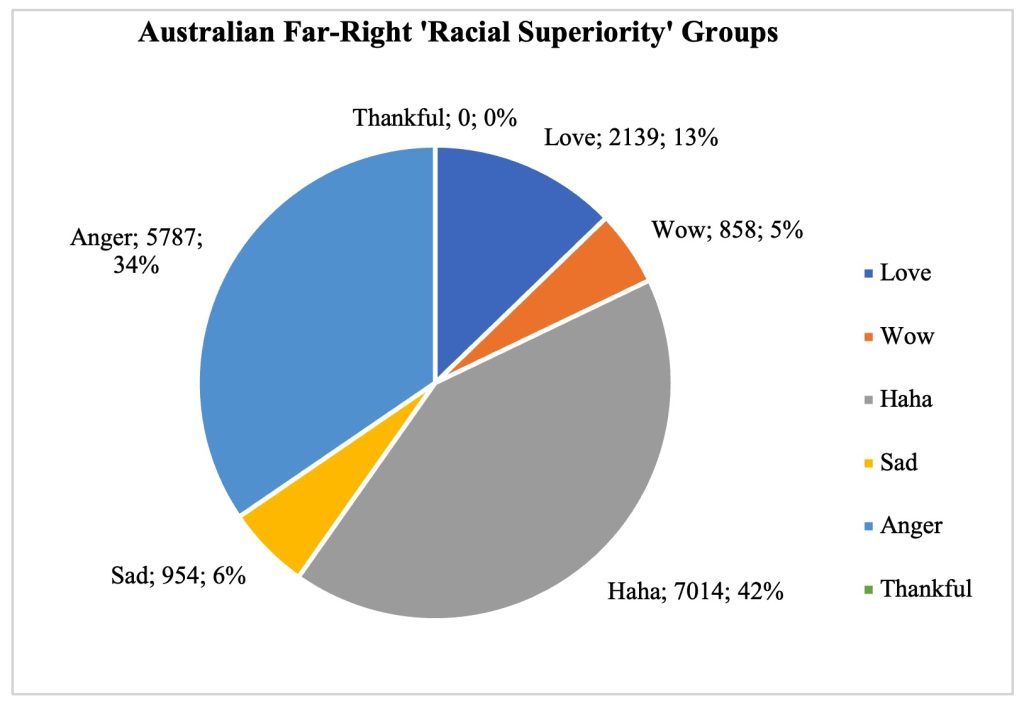

Figure 4. The frequency and proportionate use of Facebook’s reactions by users across every Australian far-right group in the sample coded as Racial Superiority from 2016-2019.

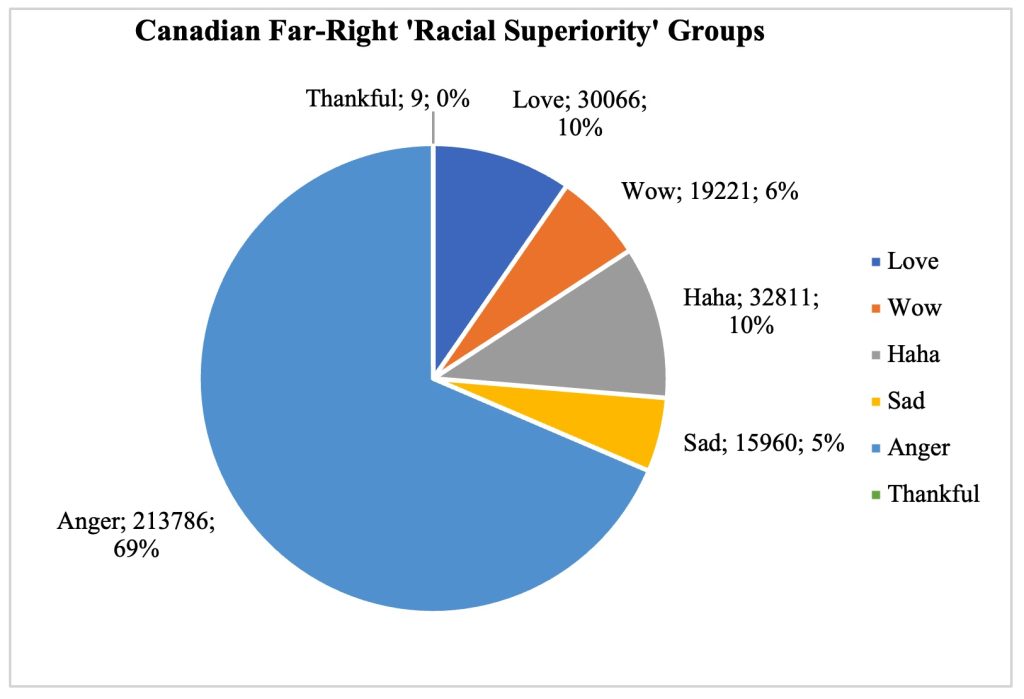

Figure 5. The frequency and proportionate use of Facebook’s reactions by users across every Canadian far-right group in the sample coded as Racial Superiority from 2016-2019.

Canadian groups coded as ‘Racial Superiority’ used 😡 ‘Angry’ (69%) at a greater percentage rate, but used 😂 ‘Haha’ notably less than adjoining ‘Anti-Muslim’ (-23.07%) or ‘Cultural Superiority’ (-58.33%) groups (Figures 4 & 5). In contrast, Australian groups coded as ‘Racial Superiority’ used 😂 ‘Haha’ (+32%) at a greater proportionate percentage rate than their Canadian counterparts, though the overall number of times 😂 ‘Haha’ was employed by users in the Canadian sample was far greater (+367%).

Micro-Level Assessment: 😡 ‘Angry’

Facebook’s 😡 ‘Angry’ was the most popular reaction among Australian and Canadian far-right extremist groups over the three-year period. 😡 ‘Angry’ was commonly assigned to depictions of ‘threating’ or ‘grotesque’ out-groups. Two identities – Muslims and ‘The Left’ – featured in the most popular negatively balanced posts. These posts consistently featured events and scenes where the out-group was presented as encroaching on native territory, operating in positions of authority, or behaving in a threatening manner with impunity.

Micro-Level Assessment: ❤️ ‘Love’

Facebook’s ❤️ ‘Love’ was the third most popular reaction among Australian and Canadian far-right extremist groups. ❤️ ‘Love’ was commonly assigned to depictions of behaviour or events aligned with far-right ideology or favourable to group aspirations. For example, these posts often contained positive depictions of local in-group identities, focusing on markers such as race, gender, politics, culture, or nationality, such as ‘Australianness’ or being a ‘white male’. Fewer, but similarly popular, posts depicted international in-group identities (for example, other far-right groups, politicians, or institutions) which seemingly favour their cause or community norms. Paradoxically, ❤️ ‘Love’ also featured on posts with a sorrowful or sympathetic framing, for example in depictions of the in-group identity suffering vicissitudes, possibly as a way of expressing shared sympathy and support.

Discussion

Facebook’s reactions, like similar features in other platforms, are designed to communicate what someone thinks, how someone feels, and signify why something is important to them and their community. Reactions are important mediators in communicating and reproducing far-right ideology because they express and embellish sentiment as well as actualise judgments aligned with community norms in a very cost-effective manner. For example, posts containing Muslims or leftist groups and institutions were densely populated with 😡 ‘Angry’ because they represent normative sources of outrage and triggers for reactionary violence among the Australian and Canadian far-right. This feature of Facebook’s interface, specifically its ability to encompass emotive as well as ideological significance, extends beyond the platform. For instance, on Reddit ‘up-votes’ were frequently attributed to posts featuring Muslims and the left. Gaudette and colleagues suggest such stories invoked an emotional response from members of the in-group and in return, ‘up-votes’ seemed to signal their agreement with or commitment to an ideological viewpoint. Social media infrastructure enables extremist groups to encode and ratify identities and stories through the collective use of mechanisms that make online communication possible. In this way, reactions allowed members of far-right extremist groups in Australia and Canada to emotionally immerse themselves in extreme sub-cultures and politics, and signal their ideological affiliation to the broader in-group.

We believe 😡 ‘Angry’ acts like a coagulating agent and persuasive instrument in online political communications, enabling members to signal their appraisal and advertise collective action. Negative symbols of emotion among politically moderate groups are partly the product of their community norms. Likewise, the use of 😡 ‘Angry’ empowers far-right extremists with an economical means of expressing and representing sentiment in response to community expectations. Additionally, a far-right community must collectively define and re-define their out-groups and when 😡 ‘Angry’ reactions accumulate on one particular out-group identity or storyline (e.g., images of immigrants or mixed-race couples), the post is transformed into something like a ‘wanted poster’ conveniently pinned with an inventory of who and how many hold similar negative judgements. Conversations about who is considered to be an out-group are, in part, sustained via posts about the ‘other’ on social media platforms. This social movement register takes on multiple functions: it manufactures and maintains shared cultural and political expectations concerning certain out-groups; signals who is sympathetic to these norms; and suggests how many may be willing to ‘defend’ the in-group community through attacking out-groups. Therefore, 😡 ‘Angry’ can be thought of as an economical means to communicate and embody basic assumptions central to far-right ideology, such as outsider norms and identities.

❤️ ‘Love’ was found to function as a way of marking the in-group community. The use of ❤️ ‘Love’ equipped members with a mechanism for recognition and grounded reasons for self-embracing or defending a collective identity. It enabled each group to celebrate their own achievements and that of their allies, but ❤️ ‘Love’ was also used to goad members into defending their in-group. When populated on a Facebook post or positioned on a person’s Twitter profile, ❤️ ‘Love’ advertised someone or an event as desirable, constructive, or worthy of championship and commemoration. However, ❤️ ‘Love’ can also function as a signal of sorrow, sympathy, and nostalgia when affixed to identities or stories of unfortunate accidents, perceived injustices as well as romantic renditions or revolutionary figures said to protect or provide inspiration for their cause. When tallied over the three years, ❤️ ‘Love’ offers an invitation for others to also symbolise their allegiance or degree of commitment to their (malevolent) ideological viewpoint.

Personalisation algorithms manipulate the frequency, duration, and intensity of the material presented to users while visiting the platform. Like any other post made by an individual, reaction usage plays a role in determining what future content a person is exposed to, including that which may support extreme worldviews and attitudes. Reaction usage, therefore, may extend the reach, permanence, and memorability of far-right extremist posts and may have incrementally contributed to the cultural and political evolution of the community.

Facebook can generate immense connectivity in and between networks of users while personalising individual experiences by manipulating the order of content. In doing so, personalisation algorithms may imperceptibly move someone towards radical cultural or political norms. Far-right extremist identities and stories construct, communicate, and categorise cultural and political opinions. Through their affixture to every post, emoji-style reactions provide users with a pre-existing set of available responses that work alongside personalisation algorithms to mould user experience. Following the instalment of reactions, Facebook announced that their algorithms weighted reactions more than ‘Likes’ when determining what content will (re-)appear in a person’s news feed. This means that every time someone assigns a reaction to a post on Facebook, the company’s algorithms registered this behaviour (together with other metrics) and started prioritising similar types of posts while gradually positioning them alongside others who behaved likewise. Of importance in this study was the popularity of in-group-out-group themes and narratives, as well as their popular pairing with positive and negative emotive symbols.

Even if the initial use of a reaction was considered ‘neutral’ (which is a response in itself), personalisation algorithms still attribute their habit of reaction use as an indicator to preferentially allocate certain types of posts in the future. And regardless of whether their decision to engage feels wilful or deliberative, when presented with numerous opportunities to symbolise and embody their emotional reaction to identities and stories congruent with community norms and values, an individual may begin to entertain the ideological viewpoint offered. For sympathetic viewers, continued exposure may arouse or strengthen an impression of their situation in a state of emergency, or in urgent need of radical action. In either case, users dwelling in far-right extremist groups on Facebook give the platform’s personalisation algorithms reasons to reorder the delivery and density of their worldview. Contextualised by their own patterns in behaviour, identities or stories of interest are prioritised and may incrementally contribute to the cultural and political evolution of far-right extremist communities on Facebook. These findings highlight social technologies like reactions and personalisation algorithms as contributive factors in the development of cultural and political norms in far-right extremist communities that, over time, create the foundations of a far-right extremist emotional and moral repertoire.

Mr. Jade Hutchinson – Cotutelle PhD Candidate, Department of Security Studies and Criminology, Macquarie University (Australia); The Research Centre for Media and Journalism Studies, University of Groningen (The Netherlands). Visiting Fellow in The Institute of Security and Global Affairs at Leiden University (The Netherlands)

Dr. Julian Droogan – Associate Professor, Department of Security Studies and Criminology, Macquarie University (Australia); Editor, The Journal of Policing, Intelligence, and Counter Terrorism.