Introduction

In the wake of Malaysia’s 15th General Election (GE15) on November 19, 2022, hate content and conspiracy theories concerning the appointment of the new prime minister, Dato’ Seri Anwar Ibrahim, surged across the Internet. Hate-inspired videos with the hashtag #13Mei became viral among the youth demographic on TikTok. Meanwhile on Twitter, posts containing conspiracy theories questioned Anwar’s legitimacy as a leader and accused him of being a CIA plant and Zionist Israeli agent.

In the build-up to GE15, contesting conservative hard right parties such as Barisan Nasional (BN), Perikatan Nasional (PN), Pejuang, and the Islamist party, Parti Islam se-Malaysia (PAS) openly engaged and deployed ‘cybertroopers’ as part of their campaigns. Cybertroopers, also referred to as ‘cytros,’ are individuals recruited by political parties or other organisations to spread disinformation, discredit rivals, derail political discourse, and manipulate public opinion online. Disinformation has become an increasingly powerful tool in influencing votes and election outcomes. By spreading disinformation, parties are able to influence public opinion and create an environment of distrust that can lead to increasingly polarised political views and divide communities. ‘Red-tagging’ is a common element of disinformation campaigns in the region, the labelling of persons or organisations as communists or terrorists in order to discredit or justify coercive actions against them. Due to Southeast Asia’s history with terrorism and insurgency, certain regimes have been known to respond violently to any suggestion of communist threats, such as violence or human rights violations against the targeted individuals or organisations, resulting in wrongful detentions and executions.

During elections, disinformation tactics are often used to achieve three goals: 1) to sway the outcome of elections by creating an environment of distrust; 2) to promote polarising ideologies; and 3) to suppress voter turnout. The use of cybertroopers has grown in recent years, and while many countries have implemented legislation to criminalise this type of election interference, Malaysia’s Electoral Commission (EC) has yet to prohibit them. Until this happens, cybertroopers will continue to pose a major problem, undermining the country’s democratic processes. This Insight seeks to explain Malaysia’s recent election experience, which was marred by disinformation and conspiracy theories, as well as increased hate speech and threats of violence, and to discuss identified risks that are associated with the use of cybertroopers as a state tool to control narratives and digital astroturfing to manufacture political support.

Understanding Conspiracy Theories in the Context of Malaysia

Conspiracy theories are just as prevalent in Southeast Asia as they are elsewhere in the world, with similar key narratives. Conspiracy theories and right-wing extremism frequently intersect; in fact, conspiracy theories can be attributed to being the driving force behind right-wing extremism. Conspiracy theories typically revolve on a perceived threat to the power and/or authority of the status quo. Those who subscribe to these ideologies frequently distort facts and portray conventional truth as an imminent attack on their beliefs, customs, and way of life. The use of conspiracy theories to drive narratives, legitimise the status of dominant groups, and increase polarisation is not new; it is often employed to radicalise and indoctrinate its intended audience.

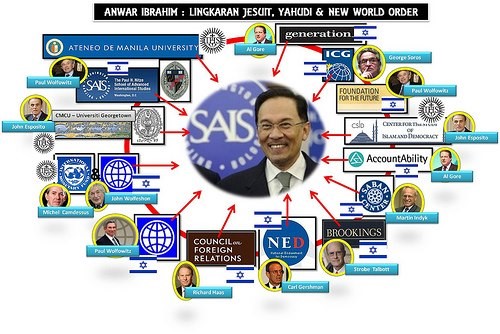

Figure 1: A chart that claims to demonstrate Anwar Ibrahim’s links with the US, Zionist Israel, and the New World Order.

Malaysia is a multi-ethnic, multi-religious country predominantly ruled by a federal constitutional monarchy, with His Majesty the King as the head of state. While the Constitution’s framers envisioned Malaysia as a secular state, Islam is the official religion with a provision for Malay special privileges, the majority of the country’s Malay voter base view Malaysia as a theocratic Islamic state. In Malaysia, the Malay-Muslim worldview is shaped by perceived victimhood associated with ideological anti-Semitism and prejudice toward the Chinese minorities, particularly the oligarch class and political elites. There is the persistent belief that the Chinese refuse to assimilate or abide by the “social contract” that recognises Malay political supremacy, and they are pejoratively labelled as “unwelcomed guests”. These prejudices create dog-whistles for an imagined enemy representing secularism, globalisation, and the so-called New World Order that entails Western imperialism and Judaic-Christian hegemony that seek to subvert Malay-Muslim values. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, these combined paranoias became the driving force of largely conservative Malays’ pro-Kremlin sympathies, as they perceive Russia to be the antithesis of the United States. Furthermore, India’s growing adoption of a Hindutva ideology that emphasises Hindu majoritarianism and serves to discriminate against the country’s Muslim population has also fuelled a localised “Great Replacement” narrative in Malaysia.

More recently, India’s turbulent politics fuelled already-existing suspicions among Malay hard-right conservatives who believe that local Indian communities, who are largely of ethnic Tamil descent, are ungrateful inferiors who may one day wish to oust Malay Muslims. This animosity intensified during the height of a panic over the separatist group Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) that fought against the Sri Lankan government during its country’s civil war, and at the time when Malaysia’s minority Indian community was expressing their legitimate grievances over discriminations and temple cleansings through the now defunct Hindu Rights Action Force (HINDRAF) in the mid-2000s. Local Tamil LTTE sympathisers were denounced as a national security threat although LTTE’s goals never included targeting Malaysia as its political ends. Despite the LTTE’s demise in 2009, this did nothing to stop increased securitisation of Malaysia’s Tamil community, and baseless allegations that LTTE was trying to resurrect itself in the country persisted.

For decades, Malay political players have been exploiting this siege mentality to acquire the Malay heartland votes without considering the potential consequences of legitimising ideas that promote damaging or pernicious ideas about minority populations. This has also fuelled opposition to ratifying the UN’s International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) in 2018, which was intended to improve the country’s human rights record. In the run-up to the 2020 political crisis, ICERD became a major point of contention to incite Malay voters against the Pakatan Harapan (PH) government. Recently, Malay ethnonationalists online are reinventing Malaysia’s historical formation narrative, claiming that ancient Indian influence was never a part of the early Malay kingdom, that Malaysia does not have a Hindu-Buddhist past, and that Malaysia has always been Islamic.

Anwar Ibrahim: A Perennially Controversial Figure

Conspiracy theories regarding Anwar Ibrahim date back to the late 1990s, owing to his close and positive relationship with his Western counterparts. Prior to the elections, Anwar’s political rivals were exploiting the fear of lost Malay-Muslim privileges by creating the tin-foil hat narrative that Jews and Christians were colluding with Anwar and the soi-disant liberal democratic Pakatan Harapan (PH) in an attempt to “colonise” the country. During the GE15 online campaign trails, a large part of the influence campaign focused on smearing Anwar, including an elaborate kidnapping plot of a Hamas member by alleged Mossad agents supposedly linked to Ibrahim’s party. Anwar Ibrahim, who served as both Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister in the 1990s, began his political career as a fiery Islamic youth leader and later joined (then-prime minister) Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), the dominant force of the Barisan Nasional (BN) political coalition. Over the next three decades, Malaysia’s politics would be dominated by the dispute between Anwar and his former mentor Mahathir, which was anchored in their opposing opinions on major political issues, particularly the Asian economic crisis of 1998.

Over time, Anwar has come to be regarded as a progressive figure, advocating for greater civil liberties and social reforms, while Dr Mahathir is renowned for taking a more authoritarian stance on matters such as censorship and the use of preventive detention laws such as the Internal Security Act (ISA). As a result, Mahathir declared Anwar unfit to govern and Anwar staged massive political rallies against him in the 1990s. As a result, Anwar was imprisoned on corruption and sodomy accusations, which were widely seen as politically driven. In 2018, Anwar and Mahathir reconciled to overthrow the political coalition they previously served, but their alliance lasted just two years until they fell out again, resulting in the fall of their 22-month-old government. The infighting was cited as the primary reason for the 2020 political crisis (dubbed the “Sheraton Move”), which resulted in the formation of Perikatan Nasional, two unelected governments, and plunged the country into further political uncertainty. The participation of the 18-year-old voting base, dubbed Undi18 (“undi” means to vote), for the first time in the recent general election altered the voting demographics. Most seasoned political observers predicted that younger voters would vote for the Anwar-led PH.

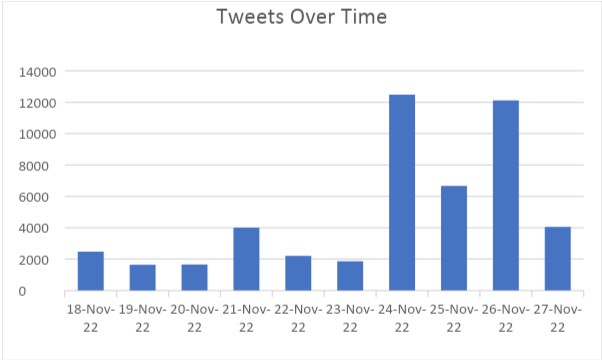

Figure 2: The graph is a sample data set demonstrating the increase of hate-mongering content and conspiracy theories attempting to undermine Anwar Ibrahim on Twitter for more than a week following the GE15 elections. A significant increase can be seen on 24 November, the day Anwar was appointed as the new prime minister.

Rage Clicks, Hatebomb and the New World Order

Instead, the elections ended with an unprecedented hung parliament that compelled the King to become the political arbitrator. What was even more surprising was that this was also caused by Undi18 that unexpectedly swung their votes to Perikatan Nasional. Allegations would later surface that young TikTok influencers were paid to disseminate political messages to appeal to their audience to vote against Pakatan Harapan. While the King consulted with members of the Conference of Rulers to decide on the next head of government, a surge of hate-motivated videos hashtagged #13Mei surfaced on TikTok and went viral among the youth online, with provocative references to the tragic 1969 Sino-Malay May 13 racial riots.

Figure 3: A screenshot of one of the #Mei13 videos that warned, “Don’t let the history of May 13 repeat itself!!!” The hashtag #ditaja (“#sponsored”) suggests the content was funded.

The riot was one of the most devastating racial conflicts in Malaysian history, in which hundreds were killed in a clash between Malays and Chinese as a result of the ruling UMNO-led Alliance coalition’s electoral defeat. Official records indicate that such unrest can occur when the status quo is challenged, and any discussion of this tragedy is strongly suppressed. The messaging in those videos was unambiguous: if Anwar becomes prime minister, there is a genuine threat of racial violence. More importantly, the “paid partnership” label showed they had been sponsored, unmistakably demonstrating their intention to stir up tensions and polarise the population.

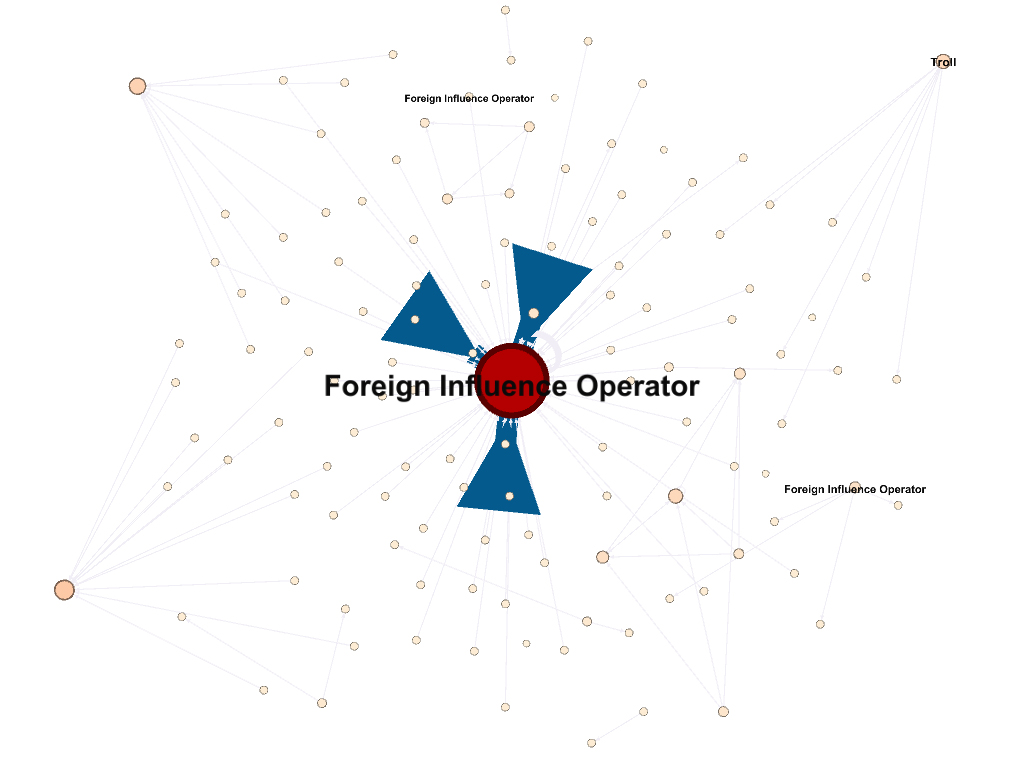

Figure 4: Social network analysis (SNA) data sampling identified three different accounts as known foreign influence operators promoting conspiracy theories about Anwar Ibrahim during his inauguration. The size of the node indicates the strength of influence, with the largest having the most amplification and interactions. The arrows indicate the direction of influence.

On the day of Anwar’s inauguration as Prime Minister, there was an uptick of hateful content online, both from Malaysian and foreign sources. Accounts linked to fringe and pro-Kremlin groups and individuals in the West known to support authoritarian regimes and whitewash genocides were spreading conspiracies that Anwar is either a CIA plant or a puppet regime installed by Zionist Israelis to advance the US and Israel’s imperial and military interests and antagonise China, via the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) organisation. The unrelenting nature of the cyber conspiracy campaigns attacking Anwar could even be compared to the Kremlin-linked 2016 US election meddling that targeted Hilary Clinton to suppress her voters and erode their confidence in her.

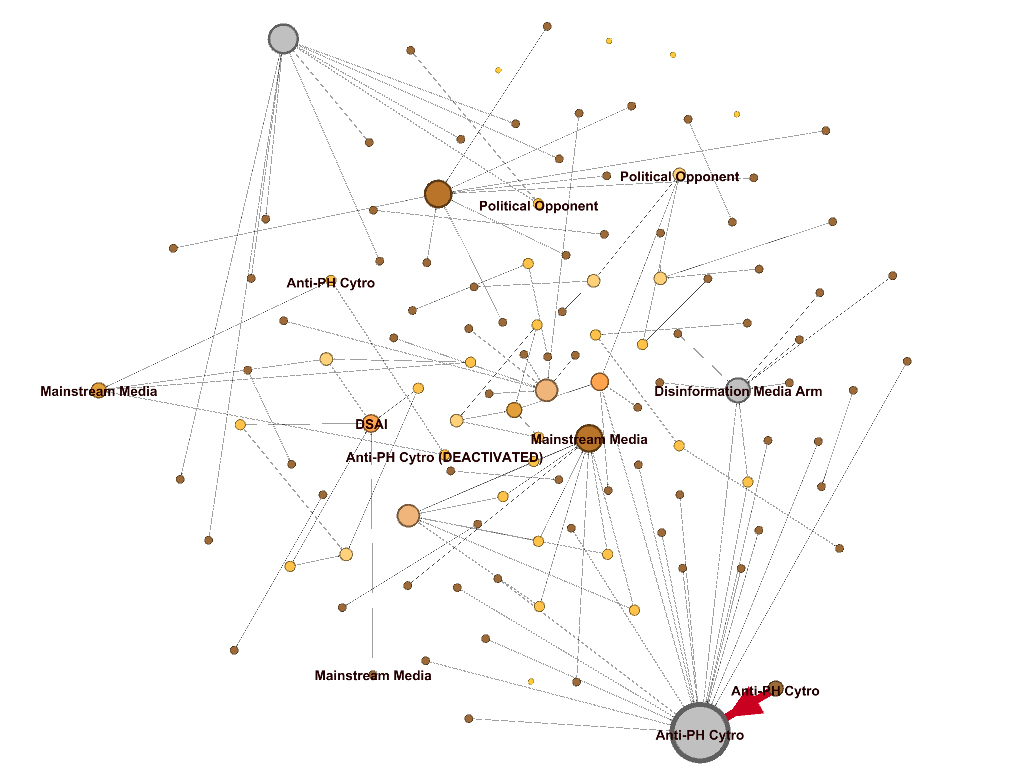

Figure 5: SNA data sampling identified local disinformation actors promoting accusing Anwar Ibrahim (designated as DSAI here) of being an Israeli plant following his inauguration. The size of the node indicates the strength of influence, with the largest having the most amplification. The red arrow indicates the direction of influence. This SNA also demonstrates the asymmetry of information wars as political rivals, their own media arm, and malicious cytros sow competing narratives against Anwar, his supporters, and the local mainstream media.

Simultaneously, PAS has been relentless and unrestrained in its disparagement of Anwar and the Democratic Action Party (DAP). DAP is described as a centre-left social-democratic political party in Malaysia. Prior to Singapore’s independence from Malaysia over ideological differences with UMNO’s Malay racial nationalism, DAP was part of the Singaporean People’s Action Party (PAP). PAS leader, Hadi Awang, went so far as branding them Islamophobic “parasites“, implying that DAP had no place in the new unity government, mainly because of its predominantly Chinese membership. On this reasoning, PAS also resorted to red-tagging by discrediting DAP as “pro-Communists” and Anwar as being a Zionist agent.

Figure 6: Part of PAS’ online hate messaging to discredit the largely Chinese DAP’s belonging in the new unity government. The poster says: “Parasites riding the coalition government”, with the word “parasite” stamped over the DAP party logo.

Identified Risks and Key Takeaways

During the general election, opportunistic malicious actors leveraged social media as a tool for disinformation to foment discord, propagating disinformation and conspiracy theories to optimise the conditions for severe polarisation, which could have ended in stochastic violence. Though the PH manifesto promised a “non-aligned” foreign policy, it is evident that there are anxieties about Anwar’s potential influence on the country’s approach to soft power. Attempts of foreign interference to influence local audiences and discredit Anwar also demonstrated that external elements are also invested in preventing Anwar’s government from undermining their own power. The use of young social media influencers to manipulate the Undi18 voting base serves as an important lesson on instilling political and digital literacy among the youth. Rather than simplifying them as “radicalised lost cause,” it is important to understand how digital astroturfing can have a profoundly negative impact on elections, and that financial incentives were the fundamental motivation for the dissemination of the hateful messaging.

Figure 7: One example of the many tweets by a foreign influence account accusing Anwar Ibrahim of being a trained proxy to serve US interest in Southeast Asia.

The issues and grievances raised during the campaign trails were not novel. This time, however, the reactionary right has become more emboldened due to various internal and external push and pull dynamics which must be identified and acknowledged. While Malaysia now finds itself grappling with what seems to be a “sudden rise in right-wing extremism,” the phenomenon in the country has never been new—only misunderstood. The mainstreaming of far-right doctrines and conspiracy theories can be linked to the proliferation of social media and algorithms that cultivate and perpetuate harmful ideology and inflict online harm, consequently jeopardising democratic processes including elections.

At the same time, extremism can also be attributed to the political establishment and leaders who exploit social strife for their own interest. Not only are malignant political actors becoming more proficient at using technology and social media for their campaign trails and messaging, but they also recognise the power of disinformation and conspiracy theories to exploit existing racial conflicts and hardline domestic politics, thus optimising the conditions for potential violence with the goal of eroding public confidence in a legitimate government. The advent of the influencer economy on social media facilitates political mischief. The new unity government must take steps to correctly identify the problem, and this requires comprehensive response.

If Anwar’s government is sincere about uniting the nation, it must introduce legislative measures to eliminate political abuse and prohibit all forms of discrimination, as the current equality provision in the Federal Constitution is insufficient to address these issues. To confront the strategic deployment of conspiracy theories and disinformation, the new government must first recognise the futility of counternarratives. Instead of forming its own cybertrooper squad to combat disinformation, the government should pursue electoral reforms by granting the Election Commission greater autonomy and agility. The EC must next consider prohibiting election interference through influence campaigns such as cybertroopers and digital astroturfing. Additionally, the new Minister of Communications must work to improve the local digital environment by increasing media literacy and improving information accessibility, so that accurate information is disseminated to the public in a timely manner to counteract disinformation campaigns. Additionally, the new Minister of Education must regulate the mushrooming of private religious schools and evaluate all current school curricula and syllabuses nationwide for indoctrinating ideas that may impede nation-building initiatives. Key to this effort’s success is for the government to recognise the need for more independent media and journalism that supports investigative journalism for accountability without fear of reprisal from ambitious local political players.