This Insight was originally posted on 25 August 2022, and is being reposted as part of GNET’s Gender and Online Violent Extremism series in partnership with Monash Gender, Peace and Security Centre. This series aligns with the UN’s 16 Days of Activism Against Gendered Violence (25 November-10 December).

Content warning: this Insight contains descriptions of sexual violence.

Introduction

Over the years, violent crimes against women have been reported with increasing frequency in the Indian subcontinent, with the crescendo of the Delhi gang rape of a 23-year-old female student on a moving bus in New Delhi in 2012. Following this incident, New Delhi was named and shamed as the rape capital of India, and massive protests by the public led to the Supreme Court enacting Anti-Rape Laws (the efficacy of which remains to be seen ten years later). Other violent crimes against women that happen with impunity in India include acid attacks on women and girls, caste-based violence against women which often boils down to rapes/gang rapes, stalking and harassment, and catcalls on the streets known as ‘eve-teasing’ in Indian parlance. India is thus no stranger to violence being meted out to women by men who feel slighted or rejected by them.

This is also indicative of the fact that casual misogyny is known to exist at multiple levels in Indian society. The question that arises from this is – are there Indian incels, and how rampant is this subculture in India?

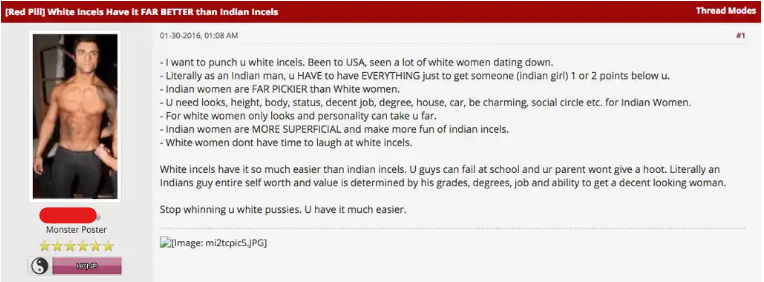

The answer to that question is yes. Indian incels are known as Currycels—a group of diverse South Asian, but predominantly Indian, men. Currycels operate on a dual level: like western, white incels, they believe they are involuntarily celibate because they are the victims of feminism and are therefore unable to get sexual partners. But, Currycels also believe they are at a disadvantage due to their race and ethnicity because Indian women prefer white men to brown men (Fig. 1). Within the broader white incel community, Indian incels are seen as particularly lacking in sex appeal; the term ‘Currycel’ itself sprung up derogatorily within the incel community.

Fig. 1: A thread discussing how Indian incels are at an even greater disadvantage than their white counterparts

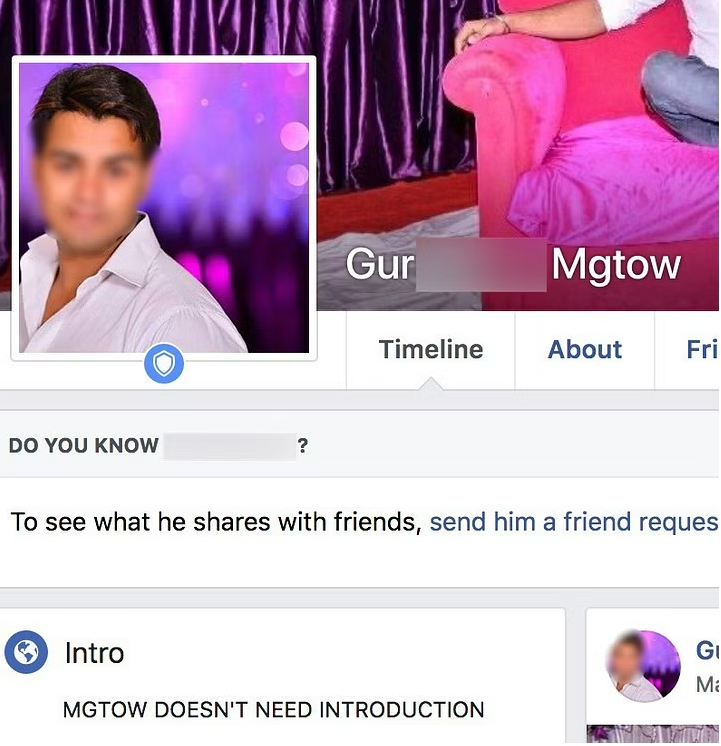

Currycels like to make themselves known publicly and can be found on Facebook and Twitter in significant numbers. Many profiles on Twitter and Facebook have their photographs on full display with their names, and these men seem quite proud to be known as such (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: A self-identified member of MGTOW on Facebook

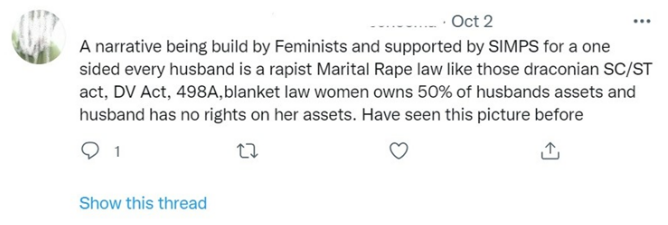

Within the larger ‘manosphere’, they self-identify as Indian MGTOWs (Men Going Their Own Way) and are members of groups such as Men’s Rights Activists in India, Gender Inequal India and Men’s Day Out (India). These are usually listed on their profiles or mentioned in their posts. Pradeep Kapoor’s book FOSLA: Frustrated One-Sided Lovers’ Association has led to the popularisation of the term FOSLA, borrowed from the book’s title, and the notion of ‘frustoos’ – men unlucky in love because it is one-sided. Particularly popular with Currycels are the terms ‘simping’ and ‘gynocentric’. Simping, borrowed from ‘Simp Nation’, is an abbreviation for ‘Sucker Idolizing Mediocre P**sy’, a man who is sycophantic and fawns over the opposite sex in a bid to attract them. Anything remotely resembling women’s empowerment or a feminist discourse is mislabeled as ‘gynocentric’ and is commonly used with Indian MGTOWs when posting a thread on Twitter or Facebook (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: A Tweet by a MGTOW supporter denouncing feminism

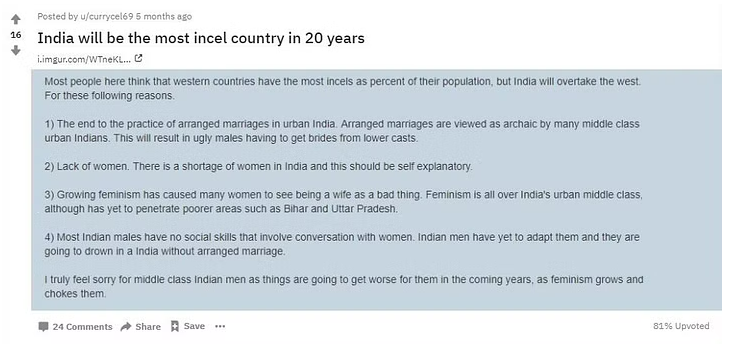

The incel community has acknowledged online that India is set to become the home base for incels in the coming years. Where has Indian society at large gone wrong that its men are prone to such brutality, violence and hatred towards its women, as seen in the Nirbhaya rape case? The answers are complex. While broadly acknowledging that systemic patriarchy is to be blamed, the nuances within the patriarchal society need to be teased out.

Son Preference

As of 6th August 2022, the population of India is 1.5 billion, and some population specialists speculate that it is slated to overtake China in 2023. Of these 1.5 billion people, youth form the largest group, and within that group, men are in the majority due to the historical tradition of son preference.

Female infanticide has been routinely practised in many parts of the subcontinent; decades of such practices have ensured a skewed sex ratio. In extreme cases, this has led to certain villages having no women at all to be married to. For example, around 350 men aged 35 or over in the village of Siyani in Gujarat – with a population of 8,000 – found themselves unable to marry.

Changing Gender Roles and Dynamics

It has also often been cited anecdotally and in online discussions by women that Indian men more broadly have not been able to keep up with the changing gender roles in Indian society. There is a nostalgic longing among these men to go back to ‘simpler’ times where gender roles were clearly defined and prescribed accordingly. Men are seemingly not able to come to terms with the new roles and possibilities of handling domestic chores alongside women (Fig. 4). Women in the urban centres are marrying later in life, and due to better education and an awareness of their rights, expect the burden of household chores to be shared equally between women and men. COVID-19 exposed this disproportionate burden on women through the lockdowns that India imposed.

Fig. 4: A post by an Indian incel

Caste

India has a complex society where caste-based hierarchical divisions intersect with expectations of traditional gender roles. This is impacted by extreme inequality in access to basic resources such as water, food and healthcare. These vectors intersect to produce dynamics in which misogyny can permeate at every level.

Sexual Division

Frustration at being unsuccessful in the dating world is often the first step for men to turn toward the incel community. For Currycels, failure and frustration is even more acutely felt due to the everyday sexual division in Indian society. Due to rampant sexual harassment, India is one of the few countries in the world where there are separate train carriages for women and even separate night taxis operated by women for women who work late at night. The extended/joint family system ensures no privacy. Sometimes, a joint family system can have multiple generations living together in a small space and it is common to share a bedroom with parents and children (for families living in shanties, there is only one room where multiple generations reside). There is literally no space in such set-ups for dating privacy and/or sexual experimentation.

Lack of Sex Education

Sex education is non-existent in most parts of the subcontinent. Most young men ‘educate’ themselves by watching pornography. India is one of the biggest users of mobile phones, and smartphones have made access to pornography even easier where one does not even need to know how to type—voice commands are enough. For many Indian men, the first time they are introduced to sex is through pornography (cumulative factors of joint family, access to mobile phones and cheap data plans). There is a vilification of sexist remarks and attitudes through pornography and coupled with the lack of sex education, attitudes within pornography towards Indian women have been normalised and commonly used as the ‘yardstick’ for sexual and romantic success (or the lack thereof).

Discussion

The term ‘Incel’/’Currycel’ is not commonly used in the Indian subcontinent to describe members of the subculture who commit hate crimes against women, and most news reports or opinion pieces are very recent (2018 to 2021). At present, there is little awareness of this subculture, and hate crimes against women are not specifically reported to the police as incel-related crimes. These terminologies are newly gaining traction in the Indian media and academic circles, but there have been no sociological studies conducted on Indian incel culture yet.

The issue to highlight is that the misogyny behind the incel discourse, particularly in a society as complex as India’s, lies on a spectrum of extremism. Laura Illya Vidal states that:

“InCel ideology is an excellent example of new radical narratives that challenge traditional images of extremism and terrorism. Despite its global reach and almost exclusively online, InCel-related mass killings have resulted in 74 deaths since the first massacre officially linked to InCel extremism in 2014 [in the West]. The increased lethality of their actions and the apparent mimicry of the modus operandi of other violent extremism has put the debate over whether InCel violence should be categorised as acts of terrorism on the table.”

It is a slippery slope where the misogynistic ideology of incels runs parallel to the gender-based ideologies espoused by terrorist groups such as ISIS. Where does it begin tipping into the well of terrorism from being an extremist misogynistic ideology? As awareness of incel-based violence increases, it remains to be seen how different countries respond to this threat. Canada has made its stance clear. India seems to be in no hurry to do so.

An Angle for Diasporic Violence Against Women

There is a large diasporic Indian community in the UK where “marriage mobility [has been] one of the primary contributors to the British Diaspora”. Rates of violence against women are high in the diasporic community, and incel extremism is one possible angle from which such violence against women can be viewed. However, since there is little awareness of the prevalence of incel-related extremism in the Indian community—domestic and abroad—hate crimes against women are neither reported nor investigated through this angle. It is imperative for authorities to consider the diasporic crimes against women through this lens.

Conclusion

Currycels have existed and made themselves known in Indian society for some time, in part through the hate crimes committed against women and in part through the online ‘manosphere’. However, connections between the online incel subculture and the broader issue of misogyny in India have scarcely been drawn, largely due to a lack of awareness by the public, the authorities and academia. It remains to be seen how India tackles the rising wave of incel-related violence, and the subcontinent would benefit greatly from in-depth academic studies on the psychosocial aspects of this phenomenon.

Dr. Gurpreet Kaur is an intersectional gender specialist. She received her B.A. (Hons) and M.A. degrees from the National University of Singapore and has a Ph.D. in Gender and Postcolonial Ecofeminism in Literature from the University of Warwick. Her interest in pursuing international law and policy towards justice was cemented during these years as she experienced first-hand through disability that disempowerment can take various forms and shapes. She is now finishing an LLM in international human rights law at SOAS, University of London, focusing on conceptions of female violence and terrorism.