Introduction

In the Salafi-Jihadist milieu, Al Qaeda (AQ) and the Islamic State (IS) are in competition to attract new supporters and communicate their organisational propaganda across the globe. Translation efforts form the backbone of all of their media initiatives. As the linguistic barriers, lack of human capital, and technical skills act as natural hurdles to sustaining a global network, these militant groups focus on bolstering their translation capacity as a part of their global media communication strategy. Over the years the Islamic State’s official media apparatus and decentralised support communities have established a variety of unofficial translation propaganda initiatives. Pro-IS media groups have established separate media wings for each language, allowing IS to communicate with various ethnic groups spread across diverse geographies.

AQ media groups, on other hand, have been falling behind in intensifying their propaganda messaging to a larger audience. Apart from Al Kifah media which translates Al Shabab’s and AQIM’s releases into French, there are evidently no other propaganda units dedicated to translating official AQ content from Arabic into separate languages. But in mid-2021, the Islamic Translation Centre (ITC) emerged as AQ’s promising translation arm with the potential of proving itself as a valuable entity in the pro-AQ media ecosystem. This Insight outlines the prominent role of ITC in AQ’s media communication space and compares this media initiative with IS-aligned translation groups. It also addresses ITC’s special focus on translating AQ’s India-focused propaganda.

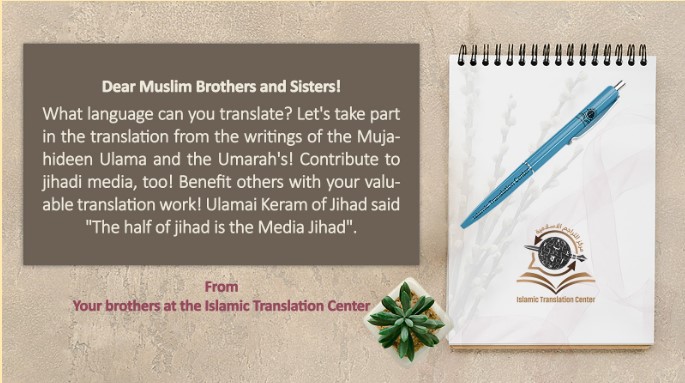

A post uploaded on the ITC website to seek pro bono translators (Image Source: Islamic Translation Centre).

Overview of IS Media Translation Arms

Academic insights by counter-terrorism researchers suggest that IS has taken the lead in diversifying its communication to a larger audience. It has been widely reported that the Islamic State Khorasan Province’s (ISKP) official mouthpiece, Al Azaim, has been internationalising ISKP’s outreach by aggressively crafting propaganda material in Pashto and translating it into other regional languages to recruit Persian, Tajik, Uzbek, Russian Kyrgyz speakers. Shoring up these efforts is another pro-Islamic State archival translation website on the dark web, Al I’lam Foundation, that offers translation of official IS content in various languages ranging from Norwegian to Urdu to Kiswahili. Another prominent IS-aligned translation group Halummu specialises in translating official IS materials from Arabic and other languages into English. However, less attention has been given to pro-AQ ITC. Below, I outline how ITC, as AQ’s sole multilingual translation website, functions with a focus on its operations in India as it competes with IS media operations in the region.

Islamic Translation Centre and its Special Focus on India

The Islamic Translation Centre surfaced online in June 2021 to compete with IS’s media warfare campaign. As AQ’s nascent multifaceted archival translation arm, ITC took on the role of translating official AQ propaganda material into 29 different languages through its growing pool of pro-bono translators. These languages include Arabic, Pashto, Persian, French, German Portuguese, Norwegian, Indonesian, Rohinya, Hindi, Malayalam and many more. ITC publishes translation of AQ’s official content, including attack claims, video releases, magazines, books, speeches of prominent leaders and ideologues and other literature. Although ITC is pro-AQ to demonstrate its neutrality, it describes itself as “an initiative that translates and publishes the lectures and essays of the Haqqani Ulamai Keram (Scholars) and the Mujahideen (Fighters) into different languages of the world”. In an effort to catch up with pro-Islamic State propagandists hailing from diverse geographies, ITC mobilised AQ supporter communities, especially those located in India, to assume the role of volunteer translators, instructing them to harness their linguistic skills to translate official AQ literature into their regional/local languages.

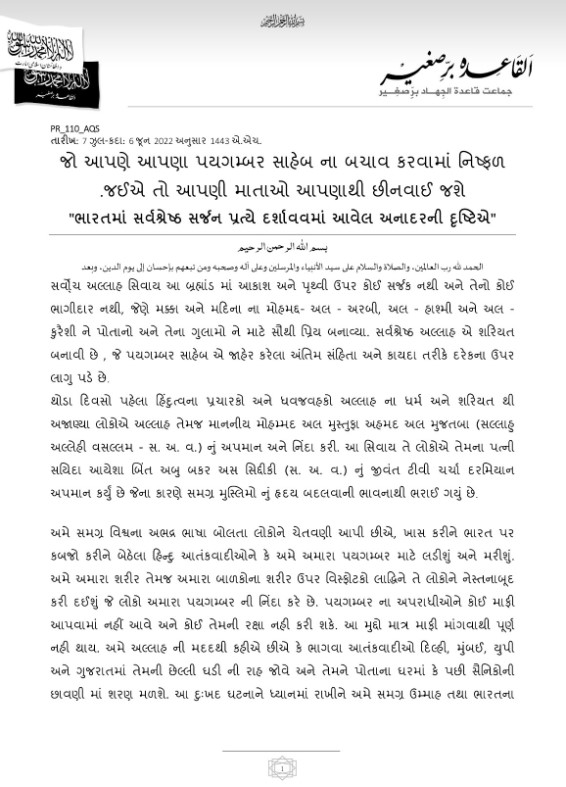

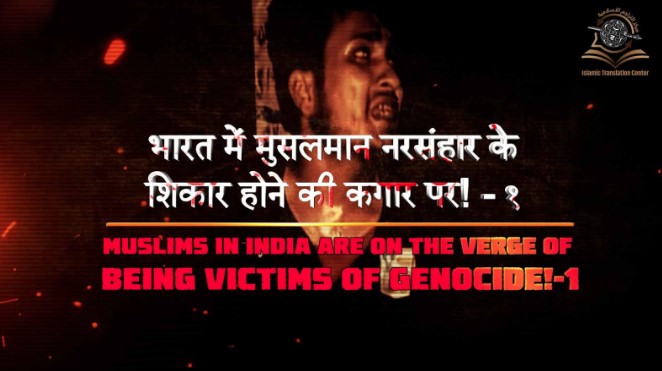

At a time when ISKP’s Al Azaim media directed at recruiting Indian Muslims has only leveraged the potential of Hindi, Malayalam, and other South Indian languages, AQ’s official content is available in multiple Indian vernacular languages on the ITC website. Indian sympathisers of AQ expeditiously translated Ayman Al Zawahiri’s long-winded speech challenging the hijab laws in Karnataka, AQIS’s threat statement of launching suicide attacks in different Indian cities over BJP spokesperson’s remarks about Prophet Mohammad and lectures of Osama Bin Laden into Hindi, Gujarati, Marathi, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, Assamese, Bengali, Odia languages. Hindi, Gujarati and Marathi comprise most of the Indian language translations on the website. These translated media releases were widely circulated on ChirpWire, encrypted applications like Telegram, and on Rocket.Chat server “Geonews” coupled with outlinks shared to other content-sharing websites like JustPaste.it, Archive.com, MediaFire, and cloud storage websites like MEGA.

AQIS’s threat statement of revenge attacks in India over the Prophet Controversy translated into the Gujarati language (Image Source: Islamic Translation Centre)

Translation of AQ’s propaganda video targeting India, translated by one of the Indian contributors to ITC into Hindi (Image Source: Islamic Translation Centre).

For a nascent media initiative, ITC’s rapid expansion in India through its volunteer translators is a disturbing development at a time when Indian security agencies have launched an aggressive crackdown against the Ansarullah Bangla Team (ABT)/Al Qaeda in Indian Sub Continent (AQIS) functionaries (both AQIS affiliates) since March 2022, preventing AQIS from making further inroads in India. Indian contributors to ITC continue to work as unofficial propagandists for AQ despite the widespread arrests of suspected cadres of Bangladesh-based Ansarullah Bangla Team (ABT) and India-based Ansar Ghazwat-ul-Hind –in Assam, West Bengal and Jammu and Kashmir. The apprehended AQIS militants have been accused of possessing Jihadi literature; violently inciting Indian Muslims to set up bases and fight in Kashmir; launching suicide attacks; planning assassinations of right-wing political leaders, and mobilising funds from AQ sympathisers in India.

The most pressing security concern for India is the terror threat emanating from the ABT in Assam and West Bengal. Assam witnessed an increase in the ABT’s militancy with the reported arrest of 40 ABT operatives since March, and the alleged infiltration of AQIS-linked ideologues into Madrasas in order to radicalise and recruit young Muslims. In West Bengal, as per the intelligence agencies, AQIS enlarged its footprint when the state government and the state security apparatus were scrambling to organise their response to COVID-19. The national lockdown also triggered the return of migrant workers to remote villages in West Bengal, allowing AQIS to further develop and entrench its network in remote corners of the state. The Indian counterterrorism agency, National Investigation Agency (NIA), and the Assam police have been alarmed by the growing number of arrests of Bangladeshi nationals associated with ABT, who, by infiltrating Assam’s porous border with Bangladesh, have established sleeper cells in Assam and expanded their networks across India.

Amidst this highly alarming situation for AQIS cadres in India, AQ loyalists continue to be able to discreetly serve ITC by communicating AQ’s message to Muslims across the nation. Thus, ITC earns a greater significance within AQ’s wider media ecosystem as it provides the AQ propagandists a sense of purpose with the advantage of cover of anonymity. The anonymity helps them evade the scrutiny and detection of intelligence agencies.

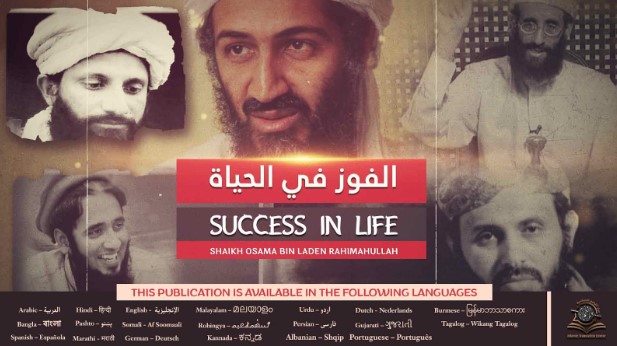

Pro-Al-Qaeda propaganda translated by ITC (Image Source: Islamic Translation Centre)

Submitting Translations to ITC

According to ITC guidelines, translators are advised to adopt a pseudonym while sending the translation drafts. The instructions further warn the contributors that due to acute cyber security threats, no translation scripts are accepted in PDF, Word or other widely used formats. ITC’s strategy relies on proactively involving AQ supporters and tangibly acknowledging their active role in the ‘media jihad’ by publishing and giving them due credit for their translations while also recognising their nisbah, indicating the person’s place of origin, tribal affiliation, or ancestry, e.g Ebu Jibril el- Filipino or Abu Saif Al Hindi. These strategies speak to ITC’s efforts to deepen supporters’ sense of belonging to the organisation, inspire them to strengthen the intra-community bonds, and reinforce their loyalty to the group. It is important to note that IS’s surface-level website Al I’lam, which is easily accessible through standard search engines and hosts multilingual IS propaganda, has been repeatedly subjected to digital takedowns, forcing it to migrate to the dark web to sustain its digital presence. By contrast, ITC’s surface-level domain has been functional since June 2021 without encountering bans or takedowns, allowing it to maintain its reach and visibility amongst its supporters. Apart from its website, ITC also maintains a presence on Telegram, Chirpwire and Al Qaeda’s Rocket.Chat platform, Geo News.

Conclusion

AQ has been profiting from the efforts of intelligence and security agencies to evict IS’s media constellations from encrypted and social media platforms. In this context, it is interesting to note that AQ Central and its affiliates’ surface-level websites have not faced scrutiny from tech giants or law enforcement agencies, allowing them to disseminate propaganda material through their website. Establishing a long-term virtual presence while bolstering its outreach and consistently publishing translations on its website allows ITC to serve as AQ’s promising multifaceted translation arm. In this way, it can play a decisive role in communicating AQ’s message to a global audience.

Considering its profitability to AQ, it would be worthwhile to monitor how ITC in the coming years works on sustaining its digital presence and expanding its scale of media translation operations into multiple languages. It would be also interesting to see how tech companies, counter-terrorism agencies, and international organisations like the UN, Interpol, Europol, and NATO view and counter the threat from ITC if in the future it plays an increasingly influential role in bolstering AQ’s outreach.

While AQIS hasn’t launched any significant attacks on Indian territory since its inception in 2014, its media propaganda has increasingly capitalised on the communal fault lines, sensitive issues among the Muslim community, and the country’s polarised atmosphere to radicalise fresh recruits. However, out of more than 160 million Indian Muslims, only a fraction of them have resonated with AQ’s brand of Salafi-Jihadism. Frequent clampdowns of AQIS’s modules across India, coupled with bellicose anti-Indian narratives prominently featured in their propaganda have brought to the fore a serious threat posed by AQIS to India’s national security.

In such a situation, Indian counter-terrorism agencies shouldn’t discount the threat emanating from Indian translators of ITC who are attempting to bridge the language gaps by making AQ’s propaganda literature largely accessible to linguistically diverse Indian audiences. They must also consider the possibility of AQIS officially recruiting these ITC propagandists, facilitating the expansion of their online recruitment campaigns in the Indian subcontinent.

I would like to offer my sincere thanks to Meili Criezis for providing her valuable input and reviewing the article.