Conspiracy theories have been talked about a lot recently as a key ingredient in the radicalisation of right-wing lone actor (RWLA) terrorists. To some extent, all narratives and ideological propaganda issued by far-right groups is conspiratorial but the qualitative difference between violence and non-violence is an important one. To what extent can conspiratorial narratives alone play a pivotal role in the radicalisation journeys of right-wing lone actor terrorists? What other factors are important for pushing individuals from radical to extremist violent action? And what is peculiar about far-right conspiratorial narratives and their ability to inspire violence? This blog post surveys the existing research on RWLA terrorists and the manifestoes of three crucial case studies (Brenton Tarrant, John Earnest and Patrick Crusius) to determine the extent to which conspiratorial language is crucial in RWLA violence.

Literature Review: Conspiratorial Beliefs versus Violent Actions

The study of conspiratorial language and narratives as a predictor of right-wing violence has experienced a boom in recent years. With a recent rise in far-right terrorist attacks, researchers have turned their interests to spotting the enabling factors in RWLA violence and how conspiracy theories may play a role within the radicalisation process. In a 2019 article, Stephane Baele asserts that – while there now exists an academic consensus stressing the importance of words that sharply delineate, reify, and polarise in- and out-group identities – much remains to be done to fully characterise this type of language and hence better understand and evaluate its exact role in violence.

In particular, Baele points out that linguistic efforts to sharpen and polarise group identities are simply too widely used by nonviolent actors to play a pivotal role in what Ingram calls the “crossing of the violence threshold.” Using the examples of the Nazi regime, the Rwandan genocide and Islamic State, Baele finds that suspected, complex, and multilayered aggression against an in-group by multiple enemies, with “World Jewry” acting as the farthest enemy, can provide legitimised violence against close in-groups (i.e. German Jews) and, from 1940, the Allied states.

Another recent study to explore the centrality of conspiracy theories within violent extremism is Gregory Rousis, F. Dan Richard and Dong-Yuan Debbie Wang’s (2020) piece exploring conspiracy theory use not just within (i.e. violent extremist groups & nonviolent extremists) but also outside (i.e. moderates) extremist milieus. Using text analysis software, the researchers coded passages of text for conspiratorial and/or violent content. What they found was that – while violent extremists were significantly more likely than the other groups to use conspiracy theories and promote violence – when it came specific conspiratorial narratives on the loss of in-group significance in violent tracts, neo-Nazis were significantly more likely than Islamic State and Al-Qaeda to promote loss of significance. This suggests that not just certain out groups but also certain types of narratives boost susceptibility towards violence.

Another study to explore the quality of certain conspiratorial narratives to inspire extremist violence specifically on the right wing is Holger Marcks and Janina Pawelz (2020) study of two online, anti-immigration campaigns in Germany. What they find is that a network of narratives where narratives of imperilment— supported by narratives of conspiracy and inequality—converge into a greater story of national threat and awakening, and that through constructing a situation of collective self-defense, violence becomes a logical option, even if violent action is not explicitly proposed. This finding resonates with other literature on the importance of certain texts in inspiring solo-terrorist actors.

A final study that provides more stable empirical flesh on the bones of theoretical explorations of the effects of conspiracy beliefs on violent extremist intentions is Bettina Rottweiler and Paul Gill’s (2020) study of the relationship between conspiracy beliefs and violent extremism in Germany. Based on a nationally representative survey of 1,502 respondents, they found that a stronger conspiracy mentality leads to increased violent extremist intentions. Most interesting, however, is their exploration of the tempering effect of individual characteristics on the extent of these violent extremist intentions. For example, Rottweiler and Gill found that individuals exhibiting lower self-control, holding a weaker law-relevant morality, and scoring higher in self-efficacy tended to have higher levels of violent extremist intentions. Such a study, therefore, chips away at the determinism that every individual harbouring conspiratorial beliefs would act out in violent ways and places front and centre individual-level risk factors in enabling extremist violence.

Case Studies: The Christchurch, Poway Synagogue & El Paso RWLA Shooters

While we do not have direct access to the mindsets of RWLAs afforded to us by surveys, the analysis of lone actor terrorist manifestoes gives us some insight into the quality and nature of conspiracy theories that motivated them into violent action. In particular, the rest of the article focuses on three RWLA attackers who have come to characterise the radicalisation trajectory, tactics and mobilisation patterns of far-right terrorism in the current epoch.

- The Christchurch Shooter: Brenton Tarrant

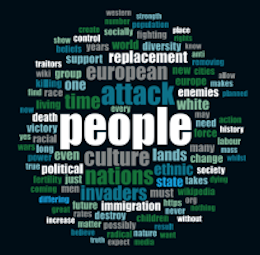

Figure 1. Word Cloud for ‘The Great Replacement’ (100 most frequent terms) (Source: Ehsan & Stott 2020: 7)

In taking the title ‘The Great Replacement: Towards a New Society’, Tarrant’s manifesto echoes a common conspiratorial theme in contemporary far-right thought – that long-established white communities are being replaced by non-white migrants throughout the Western world. The dominant thread that runs through the manifesto is the view that white people are being replaced in Western countries against their will – in both a demographic and socio-cultural sense. According to research by Rakib and Scott (2020), the term “replacement” (including associated ‘stemmed terms’ such as “replace” and “replacing”) features a total of 46 times – more than “immigration” (33 occasions). The insidiousness and immediacy of such a narrative is clearly seen by Tarrant as a basis for violent action.

As well as criticising recent processes of mass immigration, the target of Tarrant’s considerable ire and conspiratorial focus are not the Jewish or the black communities but adherents to Islam. In particular, his manifesto focuses on the fertility rates of established migrant Muslim communities in Western countries (which in turn are blamed for spurring a rapid pace of demographic and cultural change). Tarrant’s central beliefs are summarised in the bluntest of terms – writing that he is “anti-immigration, anti-ethnic replacement and anti-cultural replacement.” Most notably, Tarrant reifies Muslim migrant communities as more socially cohesive, family-oriented, and community-spirited than the materialistic individualism, celebrity obsession, and general moral decay of “Brother Nations.”

2. The Poway Synagogue Shooter: John Earnest

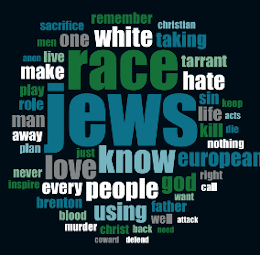

Figure 2. Word Cloud for ‘An Open Letter’ (50 most frequent terms) (Source: Ehsan & Stott 2020: 10)

‘An Open Letter’ was authored by John Earnest (at the time, a 19-year-old nursing student) before he allegedly killed a Jewish worshipper during Passover celebrations in the California city of Poway. The seven-page manifesto contains 4,216 words and was posted on 8chan.

While there is considerable overlap in the nature of the grievances raised in Tarrant’s ‘Great Replacement’ screed, Earnest (unlike Tarrant) blames a myriad of social ills and international conflicts on an “international Jewry,” and deploys more traditional far-right conspiracy theories to advance his case for violent intent. For example, he advances the view that “every Jew is responsible for the meticulously planned genocide of the European race.” The central thrust of the document is therefore that a global Jewish elite is directly complicit in the destruction of the white race – specifically people of ethnically European heritage – and that they only way to correct this trend is through violent action.

3. The El Paso Mall Shooter: Patrick Crusius

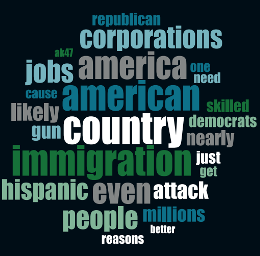

Figure 3. Word Cloud for ‘The Inconvenient Truth’ (25 most frequent terms) (Source: Ehsan & Stott 2020: 13)

‘The Inconvenient Truth’ was authored by Patrick Crusius, at the time a 21-year-old from Allen, Texas, before he allegedly killed 22 people at Cielo Vista Mall in the Texas city of El Paso on 3 August 2019. The shortest of the three manifestos under examination, the four-page document comes to 2,356 words. The choice of location and the content of post-attack interrogations suggests that the terrorist attack was motivated by anti-Hispanic sentiment, with the pre-attack manifesto itself containing white nationalist themes and ethnic replacement narratives.

Striking a similar tone to the documents produced by Tarrant and Earnest, Crusius couches his deadly targeting of “Hispanic invaders” in the language of protection and self-defence: “They are the instigators, not me. I am simply defending my country from cultural and ethnic displacement brought on by an invasion.” Though the target of Crusius’s ire is different from Tarrant and Earnest, his sense of the loss of in-group loss is similarly palpable. Crusius, critical of the market forces of globalisation, bemoans the socio-economic effects of industrial decline and the human cost of technological change in the form of automation. According to Rakib and Stott’s (2020) analysis, ‘corporations’ and ‘jobs’ (and associated terms) are two of the most frequently used words in the manifesto.

Discussion: Comparison of Violent Conspiratorial Narratives across RWLAs

| Christchurch Shooter | Poway Synagogue Shooter | El Paso Mall Shooter | |

| Far Out-Group | Migrant Muslim Communities in the West | “International Jewry” | Hispanic Population |

| Close Out-Group | New Zealand’s Muslim Diaspora | American Jews | “Hispanic Invaders” |

| Traitors (hybrid group) | Corporations and Private Capitol (“cheap labour”) | Private Capital & Modern Conservatism | Private capital & corporate-friendly parties (i.e. Democrats) |

| Contaminated in-group (hybrid group) | Broken family units &“feckless”, “degenerate”, “drug-taking” celebrity icons | Celebrity culture & the entertainment industry | ‘Corporate America’ (“shameless overharvesting”,“urban sprawl”) |

| In-Group | “Brother Nations” | White people (‘European Christian stock’) | White Americans |

Utilising Baele’s (2019) archetypes of violent conspiratorial narratives, we find interesting similarities and contrasts with the three manifestoes of the three shooters. While the targeted out-groups are obviously different and the reified in-group identities are also fairly similar, those they consider as traitors and part of a contaminated in-group are surprisingly similar across all three manifestoes. In all three, we see diatribes against social fragmentation, the rise of corporations and reactions against celebrity culture. Again, this loss of group significance is often compared against out-group populations and a more general picture of ethnic threat that inspires anger and – in the eyes of the attackers -requires violent action in order to stem the tide of an imaginary invasion.

Conclusion

To conclude, the role of conspiratorial narratives in RWLA trajectories towards violence is something that has been under-explored and under-utilised. Previous analyses have looked at group- or campaign-based expressions of conspiracy theories and their links towards violent intention and violent action rather than individual risk factors. What has been found in the above is that though the near and far out-group of each of the above attackers is different, the broad structures of their conspiracy theories and a sense of in-group loss and betrayal is palpable in their trajectories towards violence. Further research is needed to further analyse the individual psychological characteristics of these attackers as well as other contextually specific risk factors that might explain the connections between violent intentions and violent actions but the structures and examples of these real world cases at least move us closer to understanding how conspiratorial narratives – away from core extremist narratives – can move individuals towards violence.