Introduction

Corecore is a trend that gained popularity in 2022 on TikTok. Each video in the trend is a montage of multiple clips from disparate sources cut one after the other. Corecore originated from the popularity of aesthetic subcultures on TikTok that use the label “core” (e.g. “cottagecore”). Instead of outwardly identifying with a particular aesthetic, corecore clips together videos without a label, leaving the viewer to piece together the underlying link/message. I will argue that a certain strand of corecore videos can act as initiation to incel ideology.

Figure 1 displays a screenshot from each clip of a corecore video captioned “Mental Health 🧠– Part 147. #mentalhealth #coretok #corecore”.

Figure 1: Screenshots displaying a still from each clip of a corecore video posted on TikTok on 16/04/24.

The video can be described as follows:

- A clip of cartoon character Shrek complaining that people are afraid of him because he is an ogre.

- A man talking to viewers about what to expect in a relationship.

- A woman dancing.

- Another woman talking about how she is easily put off by men.

- A man explaining that a lot of men don’t know what crying is.

- Cartoon character Bojack Horseman claiming that nobody likes him.

- A solitary man lighting a candle on a cake.

It seems that this montage is telling a story, perhaps one about mental health. There are countless videos of this format, often reusing the same clips, under the label “corecore”. While the corecore trend is broad, these videos constitute a subsection that claims to concern men’s mental health. However, in this Insight, I argue that, in actuality, many engaging in this trend use the corecore format to convey misogynistic messaging. On a technical level, corecore videos use the format of found footage films. I will argue that found footage lends itself to propaganda use, as it allows for the communication of extremist narratives without the formation of a coherent argument. This can encourage an uncritical approach to complex issues and the acceptance of lazy and/or dangerous answers, which is arguably what we see with corecore.

Found Footage Films and Propaganda

Not to be mistaken with found footage horror films, the type of found footage film I refer to is one that recycles clips from pre-existing works, using montage to combine them into one. Filmmaker/historian Jay Leyda discusses the manipulative potential of found footage in his analysis of documentary films that use archival material. He argues that in these films, “the manipulation of actuality … usually tries to hide itself so that the spectator sees only ‘reality’ – that is, the especially arranged reality that suits the filmmaker’s purpose.” The filmmaker arranges a version of reality by a careful selection and presentation of clips. This selective process is hidden from the viewer, who sees only the end result. Due to found footage’s claim to deal with real footage, rather than footage created specifically for the film, viewers may be more likely to take it to be a representation of reality, rather than a manipulation by the filmmaker.

Incel Narratives

This strand of corecore videos reflect incel narratives. The term incel, short for “involuntary celibate”, became popular on the internet to describe a man who is unable to find romantic relationships or sex. The term is generally self-ascribing. Amia Srinivasan analyses the phenomenon in her book The Right to Sex. As she argues, incels cross the line when “their unhappiness is transmuted into a rage at the women ‘denying’ them sex,”. Loneliness and anger with perceived unfair treatment often turns into bitter hatred towards women, whom incels feel owe them sex. Under this view, incels resent those whom they call “Stacys”, attractive women who control the social hierarchy of dating and reject incels as lower status. They perceive “Stacys” to be superficial, hungry for money and power, and constantly unfaithful, as they will always attempt to ascend the social ladder.

The Incel Radicalisation Pipeline

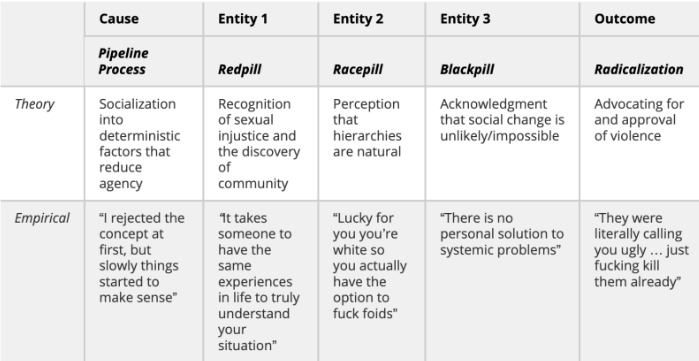

Figure 2: table tracing the blackpill pipeline process from The Black pill pipeline: A process-tracing analysis of the Incel’s continuum of violent radicalization

A recent study in 2023 described the incel radicalisation process as a pipeline with the first step being slow acclimatisation to the incel worldview (Fig.3). According to the study, “This first stage of an Incel in the blackpill pipeline is an acknowledgement of their social ostracism due to their lack of access to sex.” They cite a comment that reads, “It takes someone to have the same experiences in life to truly understand your situation.” This can create a sense of community, which then reinforces the belief that incels are victims. This first stage of acknowledgement is crucial. Though it does not explicitly encourage violence, it introduces incels to a pipeline in which violence is the end stage. The shift in worldview is essential to the acceptance of violence down the line.

Incel Narratives in Corecore

I argue that corecore videos can act as the first step in the incel pipeline, as there is an underlying incel narrative present in their editing. On the surface, these videos present themselves as being about men’s mental health and men’s suffering, potentially attracting men who may be struggling with sex but do not yet hold any incel beliefs. For example, in the video shown previously (Fig.1), we are shown a clip discussing men’s difficulties with crying and a scene of a man celebrating his birthday alone. These are both sad clips that would likely earn a viewer’s sympathy, and not for unjust reasons. Other corecore videos show similar clips of men appearing lonely and sad. However, the authors of these videos mix in clips of women in ways that often seem to reflect incel ideology.

Figure 3: Screenshots displaying a still from each clip of a corecore video posted on TikTok on 17/04/24.

To demonstrate this, let us examine a corecore video posted in April 2024 (Fig.3).

The first clip shows an interview between two guests on television – singer Ariana Grande and male interviewer Ryan Seacrest. Seacrest asks Grande if she is in love, and she asks him the same question back. He replies, “I was”. There is a cutaway to Grande, in which she says, “that broke my heart”, and back to him as he stoically repeats “I was”.

The proceeding clip is an interview with basketball player John Wall. Wall is clearly distressed. The interviewer says, “You’re never like this. She really touched your heart, didn’t she?”. So far, the connection between these clips appears to be a man expressing sadness in connection to the loss of a relationship with a woman. It is likely that a viewer would make a connection between them as broken-hearted men.

In the third clip, the tone begins to shift. We see a static shot of a man talking directly to the camera, clearly speaking to an audience. This element of direct address adds emphasis to his words. He says,

“They’ve gone to a club and they picked the biggest prick in the joint. They’ve ignored someone like me who isn’t amazingly attractive. I don’t have hench arms. I don’t talk about my gains. I just enjoy f****** food, alright. But I’m a nice guy. I’m a nerd. Alright, but you won’t pick me.”

It is unclear if he is referring to anyone specific, but it is almost certain that he refers to some group of women. He complains that they choose more traditionally masculine and attractive men over him. His body language appears agitated. His words are also accusatory – “you won’t pick me”- and gestures directly to the camera. His speech seems to contain incel ideology as he turns his anger onto women who pass him over for more attractive men. The montage editing itself seems to reflect this ideology. In the previous two clips, we are encouraged to sympathise with seemingly heartbroken men, and in this third clip, the blame begins to shift onto women. This is reinforced by the next piece of footage with a static shot of an interview with singer Billie Eilish. She says,

“Why is every pretty girl with a horrible looking man? I don’t understand. Listen, I’m not shaming people for their looks. But I am, though. You give an ugly guy a chance, he thinks he rules the world.”

On viewing, particularly after the preceding clip, Eilish’s words do seem harsh and unfair. They seem to reinforce the idea brought from the previous clip that women are shallow and unfair to men. It is almost presented as evidence. The “ugly” man talking to camera says, “you won’t pick me” and Eilish replies by discouraging women from choosing “ugly guy[s]”. There is almost a semblance of argumentation forming here – an accusation and a piece of evidence, building an incel narrative about women hurting men. However, it is expressed through found footage editing, not through words. This means that the author does not need to properly and coherently justify the incel ideology expressed. Rather, the video preys on the viewer’s emotional response to create its message. Eilish speaks almost directly to the camera, and it creates the impression that she is talking to the men watching. This could even create an emotional defensive response, which can be far more effective as a persuasive technique than a coherently laid out incel argument. In reality, these clips are extremely selective and even taken out of context. The second clip of John Wall, for example, does not show heartbreak over a woman, but his distress after a young fan’s death from cancer. However, the impression created from this clip surrounded by the others is that he is heartbroken. And in some ways, the editing shifts the blame for this onto Eilish and the women she represents. This editing may serve the purpose of initiating viewers into an incel worldview in which certain men are the victims of sexual injustice at the hands of women. They may empathise with the men in corecore and find a sense of community, sharing in their mutual suffering and potentially developing negative ideas of women.

There are countless similar examples of this kind of editing. For example, another video cuts the same clip of Eilish directly after a sad shot of actor Matthew Perry talking about a woman that he used to love whom he could never be with. This may create the implicit impression in the viewer that women like Eilish are to blame for men like Perry’s suffering. Furthermore, numerous clips are also shown of women self-proclaiming as gold diggers and cheaters. The context is, of course, removed from all of the clips. Even if they were made entirely sincerely, their use in corecore is still arguably manipulative. They are hardly representative examples of women. In the world of these corecore videos, men are largely presented as sad, lonely and caring, and women are almost always cold, shallow and rejecting. Overall, they seem to contain incel narratives without having to do the work of forming a real, coherent argument.

Conclusion

This subsection of corecore videos purporting to concern men’s mental health seems to exploit the found footage format to convey the idea that women are to blame for men’s problems. Through this, they could potentially act as initiation to an incel pipeline that ends in radicalisation and violence. However, without stating anything explicitly, the videos are difficult to identify as containing potentially harmful narratives. We should recognise corecore’s role in potentially sending individuals down incel pipelines. A potential strategy for regulation could be attempting to identify when a user is watching a lot of corecore and diversifying their TikTok feed to show a broader range of views. Furthermore, digital literacy education with these videos in mind could teach users (particularly young users) to be critical of messages in the content they watch.

Noa Rusnak is a Mathematics and Philosophy graduate, currently pursuing an MA in Philosophy and the Arts at the University of Warwick. She focuses her studies on the academic analysis of Internet trends. She is currently writing a dissertation on the ethics of recommendation algorithms.