Introduction

In May 2019, Benin suffered its first major incursion by violent Islamist extremists –likely linked to the quickly expanding militant Islamist group JNIM (Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin) – when two French tourists were kidnapped and a ranger killed in Pendjari National Park near the northern border shared with Burkina Faso. This signalled the realisation of Benin’s fears that the country would be dragged into the ‘corridor of insurgency’ in West Africa. The conflict that started in the Sahel and spread southward from Mali to Burkina Faso has now engulfed Benin’s northern frontier, with a severe escalation in attacks and fatalities since 2022.

Violent extremists are showing signs that they are distilling an understanding of the social, cultural, religious and political dynamics at play in Benin. These militants are adept at blending into local communities with whom they share ethnic and linguistic traits. To expand their footprint, these groups will assess the resilience of the social contract, particularly the socio-political culture, at various levels, from national to sentiments within individual towns and villages. Given their shared religious and ethnolinguistic overlaps, Beninese Muslim populations will be the natural targets for scouting and recruitment. Jihadist groups often gain a foothold in communities by preaching and infiltrating Quranic schools.

Today, 27.7% of Benin’s population ascribe to Islam as their primary belief system (this equates to 3.1 million people). Most Beninese Muslims belong to a handful of ethnic groups, such as the Yoruba, the Western Fulani, and the Baribia. About one in ten (11.6%) practice the indigenous Voodoo religion, while many more incorporate these traditions into monotheistic practice. The Christian population (45.8%) – largely Roman Catholics – live south along the coastline, while the sparse and majority Muslim northern populations straddle the Sahel. The latter is perhaps Benin’s most vulnerable regional geography today.

The Bariba (or, as they call themselves, the Baatanu, which translates to ‘the people’) are a historically important Muslim ethnic group in northern Benin, particularly in the Borgou area (where religious extremists have been operating in recent years). Their historical land is today bisected by the Niger-Benin border, a reality that facilitates significant cross-border movement. These Muslim communities are seen by the region’s violent Islamist groups, such as JNIM, Katiba Macina and Islamic State West Africa (ISWAP), as entry points to expand their reach and increase recruitment. As such, the communities are regarded with suspicion by counter-terrorism actors and fall victim not only to violent jihad but also to security counter-efforts. In July 2022, according to data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED), the army mistakenly killed at least four Muslim Fulanis that they falsely mistook for IS-Sahel members. Avoiding deadly blunders like these and closing the entry points for extremists requires a concerted effort that incorporates an understanding of the experiences, sentiments, and challenges of Benin’s Muslim communities. This ultimately will better inform programmes to promote, on one hand, resilience to extremist narratives via democratic efficiency and, on the other, deeper integration between ethnic and religious groups. Amidst the increasing threat of violent extremism in Benin, especially affecting the northern Muslim communities, the pressing need arises to employ ‘peacetech’ solutions like digital community building and responsive governance. These strategies aim to strengthen socio-political resilience, safeguard positive democratic sentiment, and tackle the identified gap in satisfaction with democracy highlighted by Afrobarometer data.

The Socio-political Culture of Benin’s Muslims

While there has been little research to distil their sociopolitical leanings, the Afrobarometer – a non-partisan, nationally representative public opinion survey – provides some insight. The survey data collected in 2022 had 28.7% Muslim representation in the sample (the national census puts the Muslim population at 27.7%).

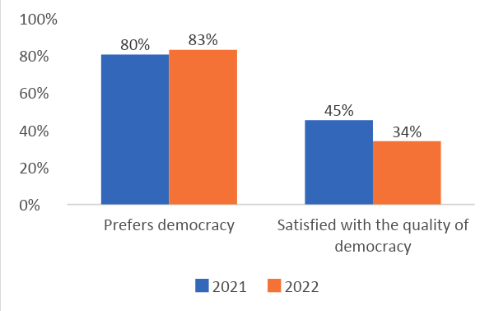

Fig. 1: Demand and supply of democracy among Muslims in Benin

When it comes to the political sentiments of Benin’s Muslims, there is an overwhelming demand for democracy (Fig. 1). 83% say that democratic governance is preferable to any other type of governance, simultaneously rejecting military rule (61%), one-man (92.7%) and one-party rule (93%).

It is, however, critical that optimism does not turn into disappointment, which can easily be exploited by populist or extreme narratives – a phenomenon now manifesting in other parts of the continent where Islamism has taken hold or grown more virulent. Worryingly, across both survey rounds, the demand for democracy outstrips the perceived supply of democracy by approximately double. Moreover, when contrasted to the previous survey round, there is a marginal increase in demand for democracy (from 80% to 83%) and a larger decline in satisfaction with the supply of democracy (from 45% to 34%). This change has taken place amid the growing proliferation of extremist narratives in the country, including a Wahabi influence with purist and anti-Sufi undercurrents. A spread of Koranic or Franco-Arabic schools has also been used to strengthen a distinct identity that delegitimises the state.

Democratic Participation

Central to closing the gap between the demand and supply for democracy is restoring trust in the democratic system through positive and sustained engagement. Although two in three (66%) of Beninese Muslims say that they do not feel close to any political party, they do exhibit some levels of willingness to engage within the framework of a democratic system – a willingness that can be leveraged for sustained resilience.

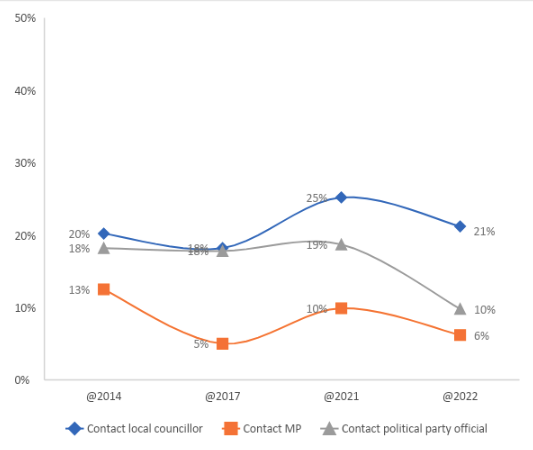

Fig. 2: How many Beninese Muslims contact an official about an important problem?

Firstly, there is a stable level of engagement with local councillors from Beninese Muslims. Fig. 2 shows that between 2014 and 2022, one in five (20% and 21%) say that they have contacted a local councillor about a problem ‘often’ or ‘a few times’. Worth noting is that between the four most recent survey rounds, there has been a significant decrease in the share of Muslims frequently contacting a member of parliament (13% to 6%) or a political party official (18% to 10%). Although this trend highlights sustained engagement at a local level, there appears to be a growing disengagement with national and political party infrastructure. Policymakers must ask the right questions, including how best to sustain local engagement, reduce the remoteness of the national government and boost the inclusiveness of the party political system.

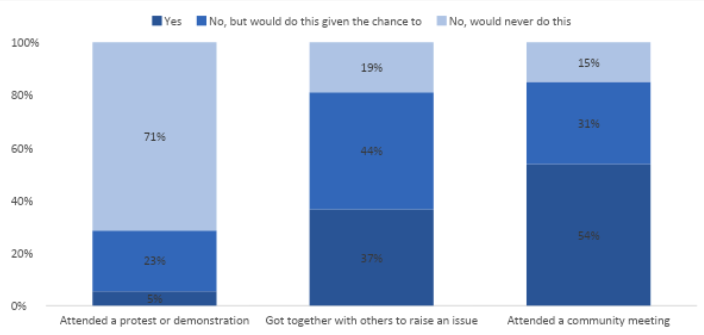

Fig. 3: Have or would Beninese Muslims engage with democratic instruments to raise an issue?

Secondly, Fig. 3 shows that Beninese Muslims are more likely to have engaged with democratic instruments through attending a community meeting (54%) or coming together as a group to raise an issue (37%), than through protest (6%). Interestingly, there is a clear willingness to do so from those who have not participated in these activities. If given the chance, one in four say they would attend a protest (24%), one in three (31%) say they would attend a community meeting, and nearly half (44%) would get together with others to raise an issue. This highlights that large portions of society are willing to engage with, but remain unengaged by, democratic channels to induce desired change.

There is also a widespread sentiment that coming together to raise a community issue with a locally elected councillor is a likely scenario (63%). Again, this reflects optimism in the democratic system and a willingness to engage its infrastructure to resolve issues. This optimism, coupled with the willingness to engage peacefully and democratically and the overwhelming preference for democratic rule over other governance types, reflect a base resilience to extremist narratives. However, short-term trends in satisfaction and engagement with democratic instruments indicate that this may be changing, and the window to protect and increase positive democratic sentiment and sustained engagement requires an urgent response.

Inter-religious Tolerance

Outside of democratic despondency, violent extremists also seek to exploit religious fault lines within societies. Measuring inter-religious tolerance and resilience to malign narratives, the Afrobarometer asked respondents about trust between religious groups and how willing they were to have a neighbour of a different religion.

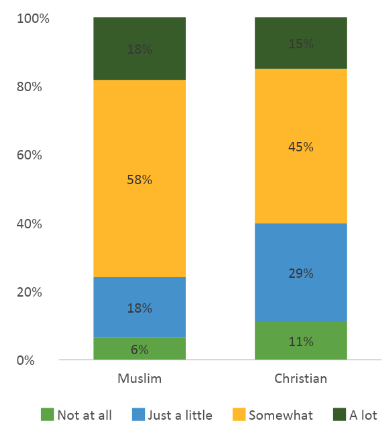

Fig. 4: Inter-religious trust levels

On inter-religious trust, Muslims are more likely to trust and be trusting of other religious groups. Fig. 4 shows that about one in five (18%) Muslims say they trust people from other religious groups ‘a lot’, while nearly six in ten (58%) say ‘somewhat’. This reflects a widespread and positive inter-religious dynamic that also translates to a willingness to live in communities and neighbourhoods with other religious groups. Six in ten (59%) Muslims and two in three (66%) Christians say they would like it if they had a neighbour with a different religion to their own. The second largest sentiment is neutrality (39% and 30% respectively), followed by a marginal few who say they would dislike it (2% and 4%).

Harnessing Peacetech to Fortify Socio-Political Resilience

Amid the mounting challenges posed by the surge of Islamist and jihadi influence in Benin, it is imperative to both reinforce the existing socio-political resilience of its communities and build out new pathways for sustained engagement that expands the inclusiveness of the political system. This resilience is a bulwark against extremist narratives and the bedrock of democracy and harmony within the nation.

A compelling avenue to boost this socio-political resilience is the strategic application of technology, especially peacetech – low-cost, easy-to-use tools for peacebuilding underpinned by technology – tailored to the unique needs and sentiments of Benin’s Muslim population:

- Digital Community Building: Construct digital hubs, mobile applications, or social networks that facilitate inter-religious dialogues and collaboration. These platforms should focus on cultivating trust between religious groups and fostering a shared commitment to peaceful coexistence. By nurturing conversations on the compatibility of democracy with Islamic principles, they can defuse concerns ripe for exploitation by extremist narratives.

- Monitoring and Early Alerts: Implement data-driven solutions to analyse social sentiment data as outlined above. These tools enable authorities to pinpoint regions where the demand for democracy is growing but satisfaction with supply is waning. By monitoring real-time trends, officials can improve their ability to respond to emerging concerns and pre-empt potential radicalisation.

- Responsive Governance enabled by Tech: Employ technology that amplifies the responsiveness of the state to community concerns and issues within the democratic framework. Develop digital channels to enable citizens to voice their grievances and feedback, establishing a direct line of communication with government authorities at the local level that can funnel upward where necessary. These channels should enable reporting issues, including service delivery, governance matters, and community requirements, paving the way for expedient responses and resolutions.

Peacetech has been successfully implemented in a range of contexts. Beninese policymakers and organisations can draw on lessons from programmes such as U-Report in Uganda, a free messaging platform designed to strengthen community development and citizen engagement that issues polls on health, education, unemployment, disease and welfare via SMS. Others include Ushahidi in Kenya, Peace Maps in Nigeria, and Mobile Vaani in India.

By embracing peacetech and crafting digital solutions especially attuned to Benin’s Muslim communities, the nation can forge a more resilient society less susceptible to extremist radicalisation. This approach is aligned with the prevailing optimism for democracy among Beninese Muslims and would help deliver on their preference for democratic governance.

The exigency of addressing the evolving trends highlighted by the Afrobarometer cannot be overstated. Safeguarding and amplifying positive democratic sentiment and sustained community engagement necessitates swift action. As Benin charts a course through the evolving threat landscape, the dynamic interplay of technology and socio-political resilience emerges as a potent instrument to counteract the reach of extremist ideologies and secure peace and unity within the nation.