Introduction

Journalists have documented instances where parents used homeschooling as an opportunity to create extremist-informed curricula in the United States – including using online spaces to disseminate content and grow virtual communities of like-minded individuals [1]. For example, in 2023, David Gilbert and Christopher Mathias investigated a Telegram channel called “Dissident Homeschool”, which promoted fascist content and shared Nazi propaganda, encouraging channel subscribers to use the material to homeschool their children. It also included homework assignments, recommended reading lists, and featured Adolf Hitler quotes that could be copied for cursive handwriting practice [2].

In an interestingly comparable but less overt situation, some individuals in a women’s only homeschooling-focused Telegram group, consisting of over 120 members, are sharing readings, lectures, guides, and forwarded posts which promote Salafi-jihadism both directly and indirectly. This Insight explores the inner workings of this group in hopes of adding to growing research on fringe homeschooling within extremist communities, indoctrinating children, and online extremist communities.

The Insight first provides a general overview of the group, followed by an exploration of the types of content that is shared, including materials created for children. It also examines strategies some group members use to convey their ideological affiliation and highlights how dissent is not tolerated in what has clearly become an echo chamber. The conclusion discusses wider implications and dynamics. For the purposes of this Insight, this Telegram group will be referred to as “Women’s Homeschooling Space.”

“Women’s Homeschooling Space”: A Content Overview

“Women’s Homeschooling Space” was created in November 2022 to, as outlined in the introduction message, help mothers support one another as they explore Islamic-informed homeschooling education options and supplemental educational resources for their children. Group members appear to be from the UK and the US mostly, while two individuals indicated they are from South Africa, one person mentioned being from India, and there may be multiple people from the Netherlands, as indicated by some members’ interest in having content translated into Dutch. In the initial opening message, the admin encouraged people to introduce themselves and stated that members could ask questions, share book reviews, send free resources, and develop lesson plan ideas. The description for the group and initial admin messages notably did not hint at any extremist leanings. However, within a month, the admin account shared content from Ahmed Musa Jibril, a radical preacher, providing more insight into the ideological affiliation of the admin(s) and, by extension, the purpose of the group. In short, the posting habits of the admin and other more prominent group members suggest that they are mixing innocuous homeschooling and religious material with extremist content to seemingly accomplish the following two overarching objectives:

- Slowly introduce extremist content to unsuspecting women who join thinking that it is a normal group seeking to help mothers with homeschooling agendas and provide supplemental Islamic education to their children.

- Remain discreet to avoid the group being banned by Telegram or attracting other unwanted attention (although the reason cannot be confirmed, many group members have been banned numerous times by Telegram, and I suspect it is for interacting/participating with other pro-Islamic State [IS] channels and groups).

Militant Content

The sharing of extremist content increased over time and broadly fell under three categories: militant preachers, posts forwarded from Salafi-jihadist-oriented channels, and overtly pro-IS content (a minority of this type of content).

Mentioned preachers included individuals such as Ahmed Musa Jibril, Anwar al-Awlaki, Abdullah al-Faisal, and Abdullah Azzam with Jibril’s content being shared the most. One post “challenged” parents to have their children “write Shaykh Musa [Musa Abdallah Jibril] and Shaykh Ahmed [Ahmad Musa Jibril] an Eid message which can be sent via email [followed by an email address].” Other content consisted of transcribed lectures, video series, and study notes created by group members to assist one another with studying Musa Jibril lectures for example.

The admin and some group members also forwarded posts and/or links directly from Salafi-jihadist channels which promoted narratives about the necessity of waging war against nonbelievers, applauded the righteousness of parents who support their children who leave to fight on the front lines of battle, and emphasised the importance of supporting people in the in northeastern Syria with monetary donations. This may initially seem insignificant, but the Telegram interface allows users to navigate to the original channel from which a post is shared, provided that the channel admins keep the channel public. In short, the act of sharing posts to a group from pro-IS channels can tremendously help members find other pro-IS content through a snowballing process of sorts. It is worth noting that numerous posts which asked for donations were shared from channels focused on fundraising initiatives from the camps in northeastern Syria.

Notably, four posts out of 3 266 messages (0.0012%) were overtly pro-IS. This included two official IS videos, an Al Naba infographic, a still image taken from a 2018 IS video showing women fighting on the front lines (fig. 1) and alleged first-hand testimony from Baghouz. Although some members evidently support IS, they seemed to understand the unspoken rule that posts of that nature should be kept to a minimum – a practice which likely has allowed this chat to remain untouched despite ongoing IS content bans on Telegram.

Figure 1: A still from an overtly pro-IS video shared in the Women’s Homeschooling Space.

Non Militant Content

Much of the content posted in the group is not militant. Examples include general religious guidance, maths practice, phonics resources, and Arabic language textbooks. Members shared advice on how to help their children benefit from and enjoy the learning process, sometimes sharing personal updates on schooling progress. Some women appeared interested in meeting in person and organising video calls to grow the community for both themselves and their children.

Some children’s workbook materials featured quotes from Jibril, but the quotes themselves were not militant. These booklets and pamphlets adopted colourful and playful graphic design styles. However, the act of normalising Jibril in children’s content through visually pleasing and friendly-appearing materials serves the following strategic purposes:

- Ensures that children see Jibril as a role model from early on and view him as a reliable individual from whom to take religious advice.

- Presents content in a disarming manner by incorporating graphic design styles that would appeal to children and/or parents wishing to use the material to teach their children.

- Promotes Jibril-approved and/or influenced content to ensure that all content is in line with his expectations. For example, channels promoting a children’s booklet about Ramadan attributed the following quote to Jibril, “I went over this booklet and found it to be a phenomenal effort….[a] huge step in delivering the pure Islam and Tawheed to our children…I ask Allah that their (the women who created the booklet) be a means to raising a new generation of muwahideen (monotheists), who will bring victory to this deen (religion).”

Conclusion: Maintaining the Echo Chamber

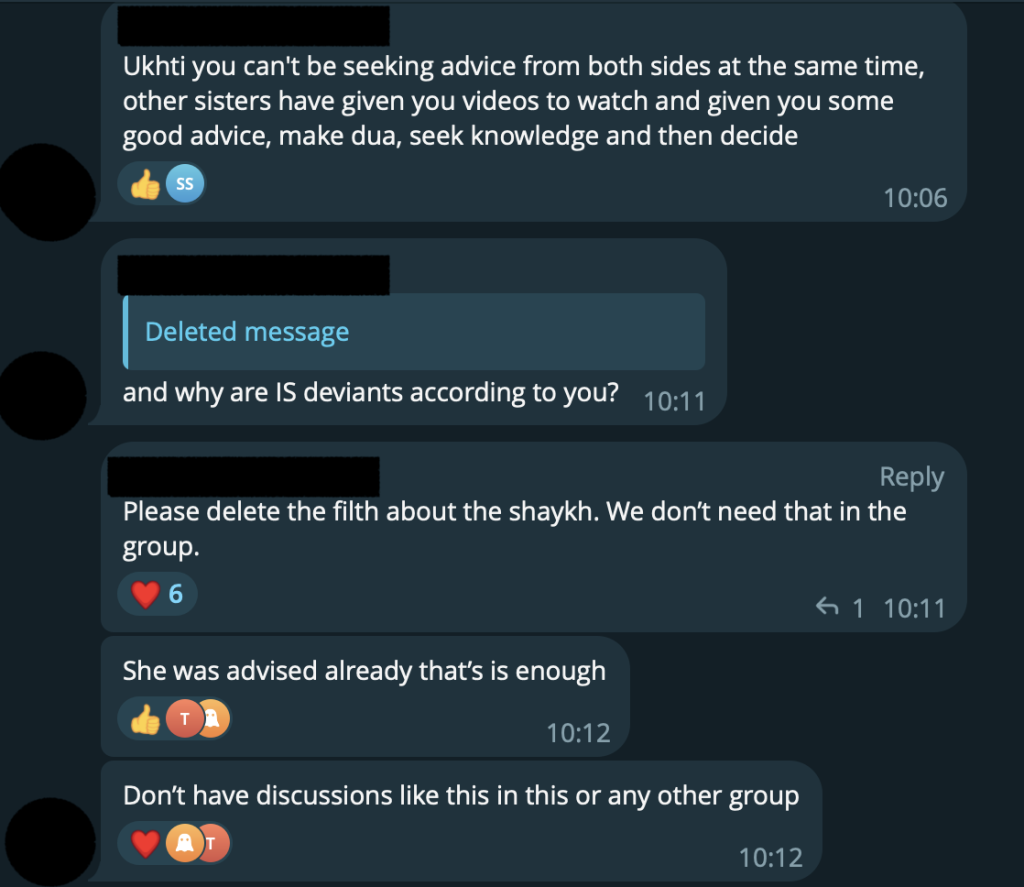

This Insight has examined the inner workings of a Salafi-jihadist-oriented women’s homeschooling chat. Unlike some Salafi-jihadist online spaces, the admin and some prominent members deliberately operate under the moderation radar when promoting extremist content. That being said, it is important to re-emphasise that it cannot be assumed that all 120+ members align with the admin and in fact, one person was promptly kicked out of the chat after she criticised Jibril and IS. She was thoroughly admonished by a handful of more vocal members, with one person asking, “and why are IS deviants according to you?” (fig. 2). Another member scolded, “Don’t have discussions like this in this or any group”, before an admin stepped in and stated that she removed the dissenter from the group and “all messages relating to such nonsense have also been removed.”

Figure 2: Discussions between group members following one group member’s critique of Jibril and IS.

However, when general questions from members appeared in the chat such as asking for advice on which scholars one should and should not follow or which materials should a convert friend read, other people were often quick to promote Jibril and similarly oriented preachers. In addition, the inquirers were advised not to listen to negative comments about Jibril and to instead seek knowledge for themselves (of course, through the resources posted in the chat). As demonstrated by the dissenter, the admin and a handful of the more vocal members did not tolerate opposition, but when people posed general questions, they were happy to provide guidance in a warm, patient manner.

Through online and offline community building, colourful children’s materials, a mix of both militant and innocuous content, and holding a place for general discussion, “Women’s Homeschooling Space” provides an avenue to introduce parents and children to extremist-informed homeschooling curricula. The method may be more discreet than the white supremacist example mentioned in the introduction, but there clearly is enough evidence proving the true affiliation of the admin and some of the more participatory group members.

Online groups such as “Women’s Homeschooling Space” are more difficult for content moderators to identify as extremist especially when group members take care to employ content moderation evasion strategies. However, many insights can be gleaned from observing their social dynamics and posting activities. For example, informing parents about discreet propagandising tactics used by extremists across ideologies and encouraging them to have discussions with their children on how to spot potentially concerning rhetoric could help parents and children alike be better prepared if they encounter such situations. For tech companies, catching the more discreet activities most likely requires human content moderators to familiarise themselves with language that reads between the lines and identify subtle in-group language that extremist accounts may use. This is not a perfect solution, though, because those who operate in the grey are practiced at toeing the line – knowing that if policies have technically not been broken, the risk of being banned decreases.

Figure 3: Homeschooling group chats directed specifically at children and youth.

Note: In 2022, the group admin created sub-groups for children and encouraged parents to have their kids join through their own accounts (fig. 3). I did not enter either of these groups, and it is unknown if they are still operating, but this demonstrates persistent efforts to directly involve children and introduce them to this online community.

Endnotes

- It is important to establish what “extremism” means. This Insight employs JM Berger’s definition of the term: “The belief that an in-group’s success or survival can never be separated from the need for hostile action against an out-group.”

- Anti-fascist researchers found the true identities of the channel owners.