Introduction

Technology, we have been told, is fundamental to winning wars. This can be observed throughout history and in current and emerging conflicts. Most recently, it has been reported that Azerbaijan is using advanced Turkish drones in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Similarly, in Ukraine, there are numerous examples of the use of advanced unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and satellites. However, ‘Operation al Aqsa Flood’, conducted by Hamas and its partners in Israel on 7 October 2023, appears at first glance to have gone against this paradigm. Home to leading military and defence engineering programmes, Israel watched its multimillion-dollar defence system struggle against forms of low-tech warfare. The resulting destruction and horror may even challenge, at least on the Israeli end, the very assumption that possessing advanced defence technology is enough to prevent mass atrocities [1].

It was bulldozers and paragliders, not high-tech arms, that infiltrated Israeli border security. It was jeeps, pick-ups, and motorbikes that allowed Hamas’s operatives to storm Israeli towns, killing and kidnapping hundreds [2]. It was this sort of low-tech breach that, arguably, caused one of the biggest terrorist attacks in history. As Israel prepares for ground operations, it might be too early to focus on what did not work at the technical level. But there is no doubt that Hamas demonstrated that terrorists and non-state actors everywhere retain the imagination and ingenuity required to overcome high-tech systems.

As such, we should expect and even accept that similar groups and lone actors may be inspired by Hamas’s attacks. But, this should not skew our understanding of the vital importance of technology to non-state actors. On closer inspection, it is clear that over the last decade, Hamas placed great emphasis on emerging technologies. The following analysis focuses on Hamas’s advanced military equipment, cyber strategy, and use of social media that contributed to the success of the 7 October attacks.

Quest for More Advanced Weapons

In terms of arms, there is nothing revolutionary about the Hamas attack. The group mostly relied on easily accessible machine guns, AK-47s and hand grenades. What is notable, however, is the trajectory the Gazan group has followed over recent years which has strived for technological advancement. Traditionally, Hamas has been renowned for its self-manufactured Qassam rockets, which granted low accuracy and high rates of friendly fire. But in the last decade, Iran started to actively support, train, and provide Hamas and its engineers with technological expertise. As a result, the group is now capable of producing rockets that can reach Tel Aviv and beyond. This is a considerable improvement compared to previous decades; in 2021, the Hamas arsenal included 30,000 missiles, according to an IDF estimate. Thus, it comes as no surprise that Hamas was able to launch more than 2,000 rockets that could both seriously challenge the sophisticated Iron Dom system and cover land incursions in southern Israel.

Fig. 1: Hamas drone in Gaza, 2021

Rockets, however, are not the only aerial system Hamas relied upon on 7 October. The novelty of this does not reside in Hamas using drones, which Iran has already supplied to friendly non-state actors, such as Hezbollah and the Yemeni Houthis. The key development witnessed during the attack on Israel is the strategic use the group has made of such weaponry. Relatively cheap and homemade drones also targeted high-tech sensors and communication towers scattered across the Israeli fence, jamming communications and taking the IDF by surprise. Perhaps not coincidentally, Hamas seems to have successfully applied what the Russians and their Iranian-made Shaheed drones have achieved against Ukrainian forces. That said, the fact that Hamas managed to target and disable an advanced Merkava 4 tank on 7 October is an indicator of their growing technical capabilities. As Israel prepares for invasion, the threat of Hamas deploying swarms of small, homemade drones (Fig. 1) could significantly impede Israeli military advancements in the Gaza Strip.

Cyber Strategy

Hamas has changed considerably since its inception in 1987. Born within the context of the First Intifada, the group now counts almost 40,000 operatives and is involved in a wide array of activities, including the running of hospitals, schools and other vital services. What is perhaps a lesser-known fact is that Hamas has its own cyber department waging war on Israel for at least a decade, which includes the use of malware for cyber espionage and information gathering. In 2013, for instance, the group lured Israeli governmental and critical infrastructure workers through pornographic material. Starting in 2015, Hamas targeted IDF personnel with fake Facebook accounts. Figs. 2 and 3 below show fake accounts utilising credible images and ‘likes’ to well-known Israeli accounts, including news agencies, and corporate and politicians’ pages, thus adding credibility and authenticity.

Fig. 2: An example of a fake Facebook account used by Hamas

Fig. 3: The ‘likes’ featured on the previous Facebook account grant an authentic appearance

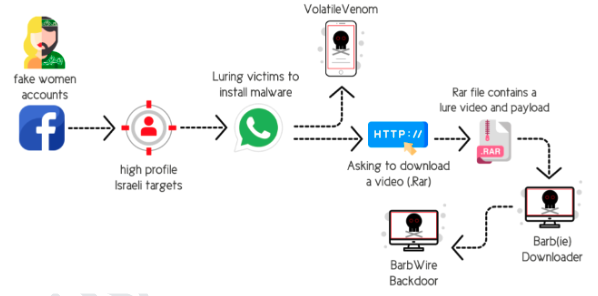

Following this, in 2018 the Hamas cyber division hacked the devices of IDF soldiers jogging in sensitive areas through a fitness app. It also infiltrated entire groups of IDF soldiers watching the 2018 Football World Cup from their bases through the Golden Cup app. In 2020, Hamas used dating apps such as Catch&See and GrixyApp. Finally, in 2022, Israeli firms identified two unknown advanced malwares which utilised stealth systems to stay undetected. As shown in Fig. 4, the process would be as follows. First, IDF soldiers would be approached on Facebook, then the conversation would move to WhatsApp. As chats revolved around sexual content, targets were lured into downloading a seemingly more secure and confidential Android messaging application. Finally, as soldiers download a .rar file featuring pornographic videos, their devices are infected with malware.

Fig. 4: Hamas’s process for infecting targets’ mobile devices with the latest malware

In the end, it is believed that Hamas managed to hack multiple IDF soldiers’ phones, cameras, and files, allegedly acquiring details of military bases and armoured vehicles in Southern Israel. Identifying Hamas’s cyber capabilities as a considerable threat; in 2019, the IDF bombed the organisation’s cyber headquarters, making it one of the first kinetic Israeli operations in response to cyber-attacks. Nevertheless, the group’s skills have remained strong, with Israeli cyber defence firms describing Hamas’s capabilities of reaching new levels of sophistication. Despite this, it remains unclear when the 7 October attacks were planned, although it has been hypothesised that it started two years ago. While it cannot be known with certainty, it is safe to assume that within that period, Hamas might have used the above cyber-attacks to gather critical bits of information to launch its latest offensive.

Social Media

In essence, terrorism is one of the purest forms of psychological warfare and propaganda communication. Terrorism is built upon deception, secrecy, surprise, and a desire for media attention. As Brian Jenkins argues, terrorism without the media is nothing. In this sense, Hamas is a case in point. The organisation demonstrated its full understanding of psychological operations. Lagging behind Israel in many areas including technology and personnel, Hamas has realised that attacks must be amplified as much as possible to blow the threat out of proportion, impact the enemy’s morale, and galvanise like-minded individuals everywhere. Within this picture, Hamas’s use of social media has been an invaluable strategic tool amid its surprise attacks. During and after the attack, Hamas operatives flooded the web with dozens of graphic, gruesome videos and images of indiscriminate killings to spread terror and a sense of helplessness among the Israeli population. Live recorded through mobile phones and bodycams inside private residences, videos included the shooting, bombing, and stabbing of innocent people.

Even more disturbingly, Hamas then released videos featuring physical and psychological abuse of abducted prisoners, including children and elderly citizens. Here, two examples are worth flagging. One features raw footage of a 25-year-old Israeli woman as she is being forcibly dragged away from a music festival in the desert: her cries begging for her life went viral in a few hours. The other instance consists of videos showing Hamas’s operatives holding abducted Israeli toddlers. This sort of psychological campaign was so effective that Israeli authorities, fearing the release of execution videos, urged families to delete TikTok, Instagram and other social media apps, with psychologists predicting longer-term mental trauma for Israel’s younger generations [3].

A Final Note

While major lessons at this stage could be premature, among the many considerations that could be made regarding the role of technology, two are worth reiterating. First, the 7 October attacks show that technologically inferior actors remain highly capable and dextrous against better-equipped state adversaries. Hamas has reiterated once more that terrorists are smart; they learn, adapt and, wherever possible, mirror governments in their attempt to obtain means that grant them a strategic edge.

Second, as we frame the role technology plays in conflicts, more caution is warranted. Certainly, every war and every military confrontation comes with its own set of dynamics, but the Hamas attacks are a case in point when it comes to technology: high-tech defence means everything and nothing. Having blind faith or, conversely, distrust in defence engineering may not account for the entirety and complexity of the threat. As was the case prior to 9/11, no matter how much technology is used, and how advanced it is, human intelligence remains and will continue to be a determining factor in the conduct, preparation, and possible prevention of any operation.

[1] However, we know that when it comes to attacks with strategic planning at the level of surveillance and the use of urban guerrilla warfare, with previously studied targets, the results are generally achieved.

[2] Yet to be confirmed, there may have been strategic cuts in the IDF’s communications structure, causing interference in the response capacity.

[3] As previously discussed, this phenomenon of the psychology of terrorism dates to the beginning of the conflict in Iraq in 2005/2006, where the genesis of what is now the Islamic State resorted to beheading videos, having been used exponentially in Syria and Iraq with the conquest of Mosul in June 2014 and subsequent years. The similarities in the use of social networks are very similar between the two groups (Hamas – Daesh), and official co-operation has yet to be confirmed. Something that was already confirmed in the past was the passage of wounded ISIS fighters through the tunnels, via Sinai, directly to Gaza.

Dr Michele Groppi is a Lecturer in Defence Studies at King’s College London and President of ITSS Verona. He is an expert in terrorism, counterterrorism, Islamist radicalisation, violent and non-violent extremism.

Dr Vasco da Cruz Amador is an Assistant Professor in Psychology of Intelligence Analysis, ISCSP at the University of Lisbon and Director of Cyber Intelligence & Cyber Security Training to the Iraqi Security Forces on the ground. He is an expert in cyber security, terrorism, counter-surveillance and counter-intelligence.