The recent political crisis between India and China precipitated by the clashes on the disputed border between the two states which saw 20 Indian soldiers killed in June, and an unidentified number of Chinese casualties, has brought forward technology as a premier focus of realignment of bilateral relations between the two Asian nuclear and economic powers. Over the past few months, India has banned dozens of Chinese apps, launching a wave of indigenously developed alternatives taking on users by the millions in a short period of time.

However, the fast-paced acceleration of indigenous consumer digital technology in India in light of the crisis with China requires deliberation on not just security with regard to data, technologies, IPR and so on, but usage of these platforms itself, building a robust ecosystem where non-state armed groups, such as Islamic State (IS) and others, who have developed successes in both propaganda and radicalisation are unable to easily migrate. Smaller technology platforms largely based out of the West have slowly yet steadily recognised the threat of being misused by radical groups from all backgrounds and ideologies in not just messaging and propaganda, but terror finance, recruitment and other aspects as well.

India’s App Boom

Between June and September 2020, India’s Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) blocked more than 220 Chinese apps, citing national security and sovereignty concerns, specifically their poor data practices.

Prior to the ban, free Chinese apps dominated the Indian app economy, buoyed by a booming Indian mobile user base with an appetite for free-to-use apps. Well-known apps like TikTok, PUBG Mobile, along with lesser-known ones like SHAREit (file sharing), BeautyPlus (photo editing) and Turbo VPN had downloads numbering in the tens of millions.

The void left in wake of their forceful exit from app stores has been rapidly filled by Indian counterparts. The government held the AatmaNirbhar Bharat App Innovation Challenge to encourage up-and-coming developers. In parallel, existing apps like PLAYit, ShareChat and Vido saw their monthly downloads rise, while newcomers like Josh, SHAREKaro and Kaagaz Scanner have rapidly climbed up the app charts.

| Name | Type | Downloads on Google Play (as on Oct 2020) | Parent Company | Launch |

| Josh | Social | 18 million | Verse Innovation | September 2020 |

| Chingari | Social | 1 million | Chingari | November 2018/ Re-launch June 2020 |

| SHAREKaro India | File sharing | 11 million | Appyhigh Technology | June 2020 |

| PLAYit | Video player and editor | 17 million | Yuvadvance Internet Private Limited | November 2019 |

| Moj | Social | 12 million | ShareChat | November 2020 |

| ShareChat | Social | 8 million | ShareChat | December 2014 |

| Wynk Music | Music | 5 million | Airtel | September 2014 |

| Vido | Video editing and animating | 4 million | Vido | January 2020 |

| JioSaavn | Music | 5 million | Saavn Media Limited | September 2016 |

| Bharat Scanner | Scanner | 90k | KickHead Softwares Pvt Ltd | June 2020 |

| Mitron | Social | 80k | MitronTV | September 2020 (Re-launch) |

| Kaagaz Scanner | Scanner | 300k | Sorted AI | June 2020 |

Table: Abridged list of Indian apps on Google Play’s “Top Free” charts, Nov 2020 (compiled by Trisha Ray)

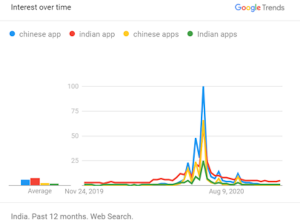

The average Indian app user also appears to be far more conscious of the origin of the apps they download. Search interest in the term “Indian apps” and “Chinese apps” shot up, and the reviews for Indian apps are frequently appreciative of their native origin. Indian apps have also been taking advantage of the geo-political shifts against China by attracting Indian users to ‘Indian’ technologies. Such a ‘shift’ has not been observed previously, both politically and academically.

Fig: Google Trends: November 2019- November 2020 for “Indian apps” and “Chinese apps”

The flipside of the rapid, sudden growth in the user base of Indian apps is increased scrutiny of privacy features and – for social apps – content moderation. Chingari, one of the winners of AatmaNirbhar Bharat App Innovation Challenge, is seeking to expand its content moderation team to keep up with its user base. A more egregious example is that of Mitron, a similar app, which was suspended from the Play Store. Its privacy policy is weak at best, lacking any detail on security and data protection measures. The app also appears not to have a content moderation policy.

The Challenge of Tackling Extremist Content

This rapid development and launch of indigenous apps, which includes messaging apps, brings forward the question of their vulnerabilities against extremist groups co-opting platforms for communications, dissemination of propaganda and developing ecosystems in and around lesser known digital platforms, run by small teams and in some cases even just individuals, that do not possess both the expertise and resources to tackle extremist content. Previously concerted crackdowns by larger social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and now even Telegram have shown us that the fast and effective takedown of extremist content, even in the most straightforward cases, is not a black and white situation. Any effective response requires close collaboration between technologists, coders, political scientists, social scientists, civil society and other fields to develop effective policies where intersections on issues such as freedom of speech, safe online spaces and moderation of content can be discussed, and more importantly implemented via policy specifically developed to counter such threats.

It is also imperative to remember that developing such policy and debates is a time consuming and resource-intensive process, especially given the fact that today social media is extremely intertwined with the public sphere, and users’ daily consumption of news and views. These challenges are magnified even further in complex democracies such as India.

These growing challenges will plague Indian apps for months, if not years to come, and getting a head start on the challenges of content moderation and threats of platforms being used as springboards by terror and extremist groups will bring a larger set of questions for both Indian public and private sectors in light of this rapid indigenisation. Different platforms’ variable answers to questions like “what is radical content?”, “What is a radical/terror group?” will create untenable solutions. These challenges are perhaps best highlighted by scholars Chris Meserole and Daniel Byman, who believe that individual companies developing in-house expertise on extremism and terrorism is unviable, and that platforms and companies are better-off choosing between existing imperfect strategies that are already in play. A simple task of defining groups that can be moderated on extremism for newer Indian tech platforms could in itself be much more challenging for their larger security framework than cyber-attacks, data protection and so on, that have technology-led solutions.

Content moderation has proved to be a messy business even for social media giants, and these new Indian entrants, that eventually will look at an international audience, will need to rise to the challenge should they wish to sustain growth and learn from the issues that have plagued the likes of Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and others.