In recent months there has been a concerning number of kids and teenagers arrested for extreme-right-related terrorism offences across Western Europe. “We are Generation Terror!” Youth-on-youth radicalisation in extreme-right youth groups provides an initial contribution to this field by exploring the ways 10 young racial nationalist groups across Western Europe recruit, radicalise, and attract other young people into their movements.

Youth Radicalisation on Social Media

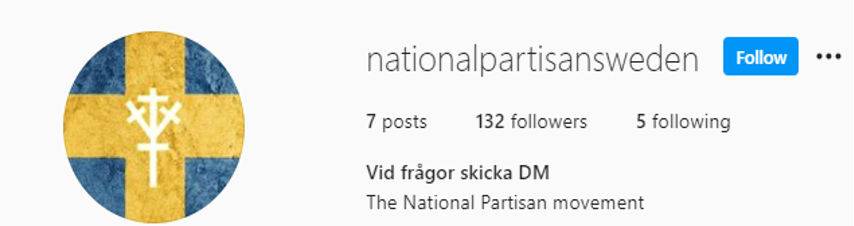

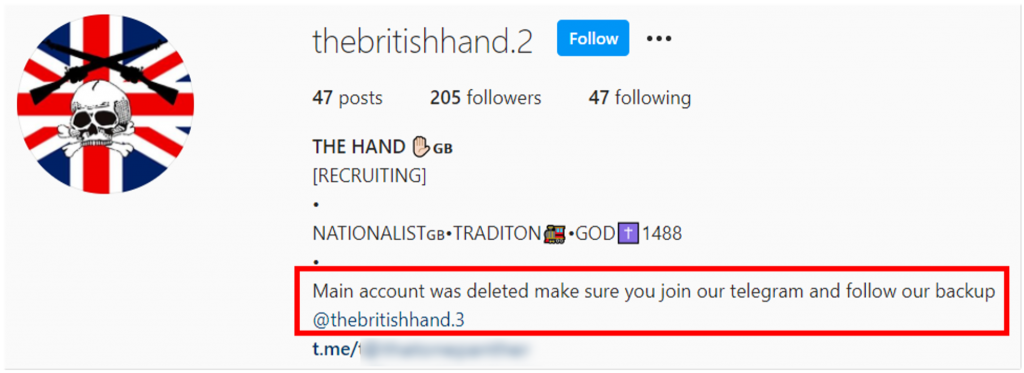

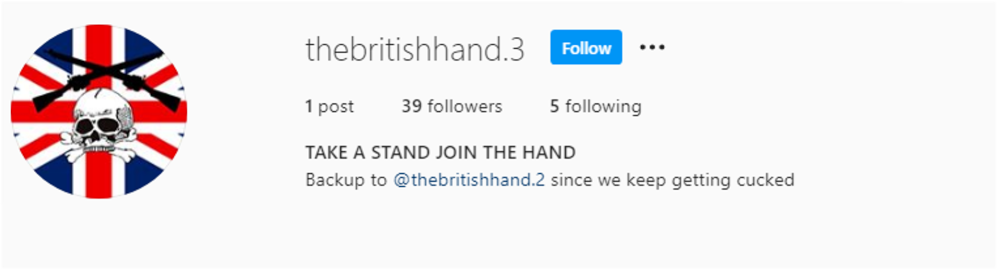

“We are Generation Terror!” highlights the role played by mainstream social media platforms in the process of youth-on-youth radicalisation. Young extremists value having a presence on mainstream social media sites such as Instagram, Twitter and TikTok, since these have significant numbers of young users active on them, and as such they appear to play a key role in enabling these groups to reach out to wide audiences within their target recruitment age. Instagram was particularly popular among the studied groups. As shown in Figures 1 and 2, groups such as the National Partisan Movement and The British Hand were active on Instagram since their very start, using the platform to spread the word about their group and seek new recruits.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Groups often create localised recruitment profiles on both Instagram and Twitter, aimed at reaching out to the youth in a specific country or region in which the group is active. This enables young extremists to tap into local grievances, therefore increasing the resonance of their message among young people in that area.

Figure 3

Figure 4

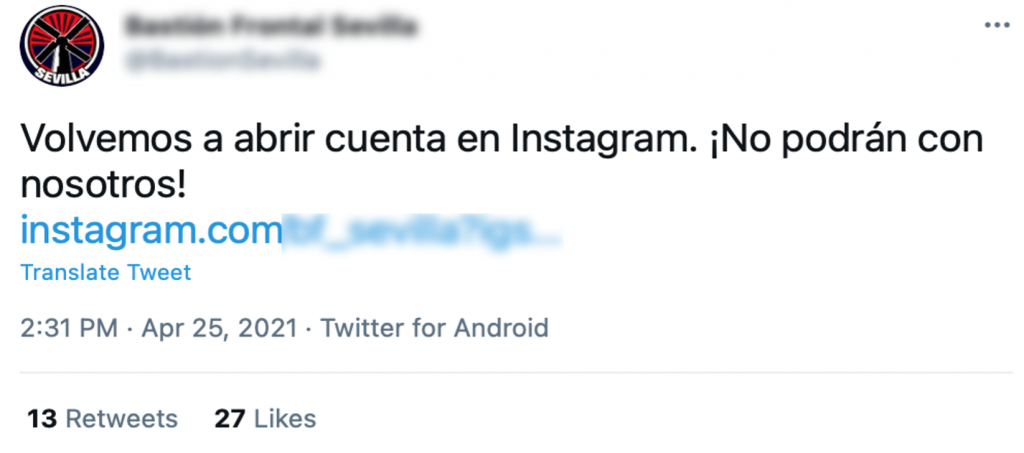

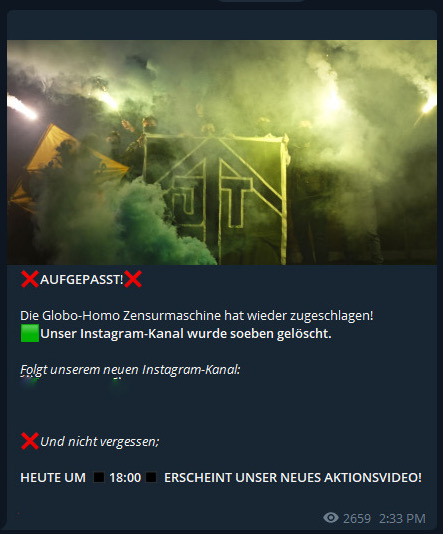

The value placed by these groups on having a presence in mainstream social media platforms is reflected not only in their continuous and regular use of Instagram and Twitter for recruitment, but also in their persistence in continuing to create new accounts on the platform no matter how many times these get suspended. Figures 5 and 6 show examples of how both Junge Tat and Bastion Frontal have created new Instagram accounts following previous ones being suspended.

Figure 5. Translation: “We have created an Instagram account once again. They can’t beat us!”

Figure 6. Translation:

❌ ATTENTION! ❌ The Globo-Homo censorship machine has struck again! 🟩 Our Instagram channel has just been deleted. Follow our new Instagram channel: 🟩REDACTED🟩 ❌And don’t forget; OUR NEW PROMOTION VIDEO WILL APPEAR TODAY AT 6:00 PM!

Young Extremists Circumvent Platform Moderation Mechanisms

Given the central role played by mainstream social media platforms in enabling extreme-right youth to recruit other young people, it is no surprise that young extremists appear to have come up with innovative ways to continue to recruit on mainstream social media platforms despite their terms of service and community guidelines. In particular, there are two distinct mechanisms identified in the report through which young people appear to be circumventing platforms’ moderation attempts.

The first is the creation of backup accounts, namely secondary accounts created with the knowledge that a primary account is likely to be suspended as a result of the content shared on it. A number of groups studied have created multiple backup accounts on Instagram, whereby on their original account they signpost to this secondary account. As such, once their primary account gets suspended, these groups can continue to share the same hateful message on this platform with the secondary account, while evading typical deplatforming consequences such as loss of followership. And once this secondary account gets suspended, they can continue doing so on their tertiary account, and so on. Typically, a new account will recommence a three-step warning process for content moderation, even when it is clear that the user has previously been blocked for promoting extremism.

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

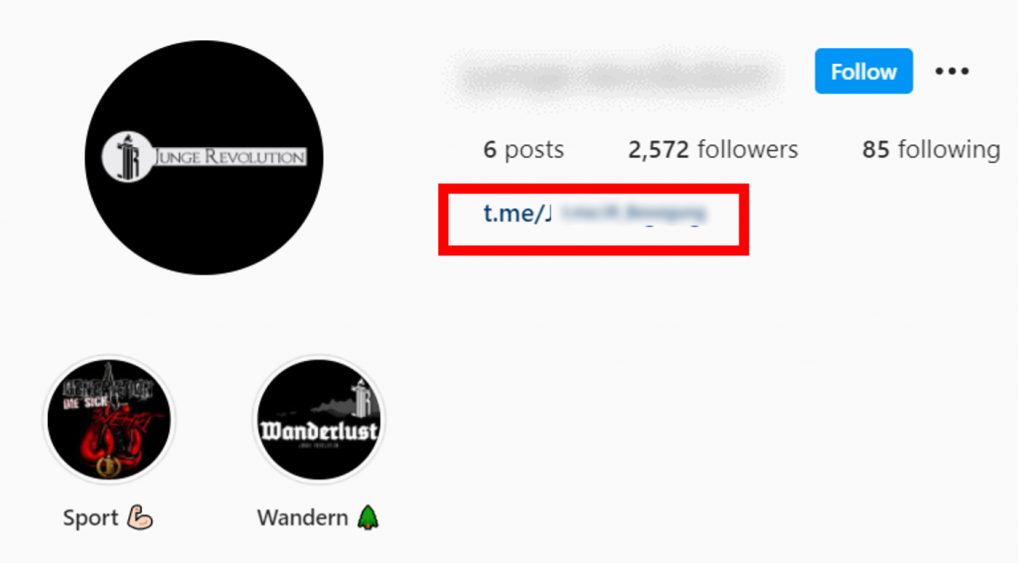

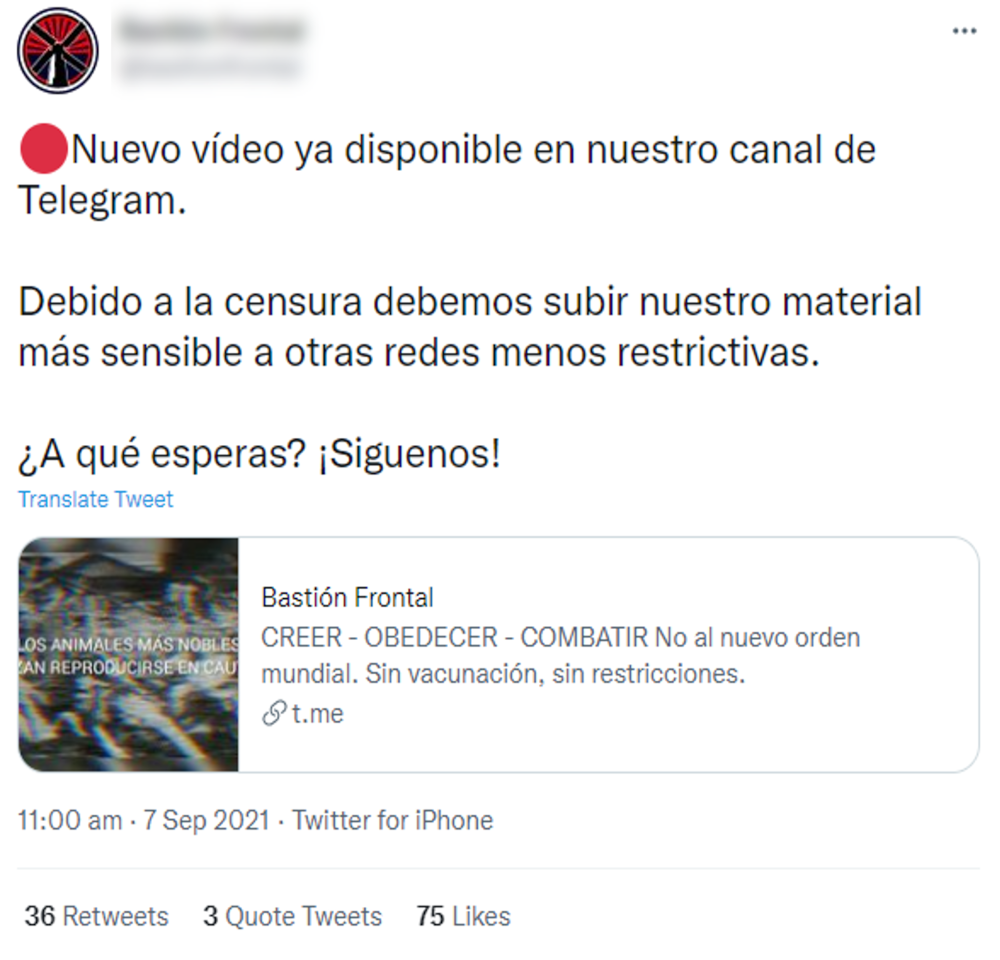

A second mechanism through which extreme-right youth appear to be making use of mainstream social media platforms to recruit other youth is through content funnelling; namely the use of one platform, in this case Instagram or Twitter, in order to re-direct users to another platform, usually Telegram, where more extreme content is hosted. This process is employed by a significant number of youth groups. Groups conduct this funnelling by including the link to their Telegram channel on the biography section of their Instagram or Twitter profile, exemplified below by Junge Tat and Junge Revolution.

Figure 10

Figure 10

Figure 11

Groups appear to explicitly urge users to visit their Telegram channel to continue to consume certain content. In the tweet below, for instance, Bastión Frontal explicitly claims that due to Twitter’s moderation policies they “must upload our most sensitive material to other less restrictive networks.” This tweet includes a link to a video on their Telegram channel in which Bastión Frontal claim that “death is a mission,” a level of incitement which would likely have resulted in its removal had it been posted directly to Twitter.

Figure 12

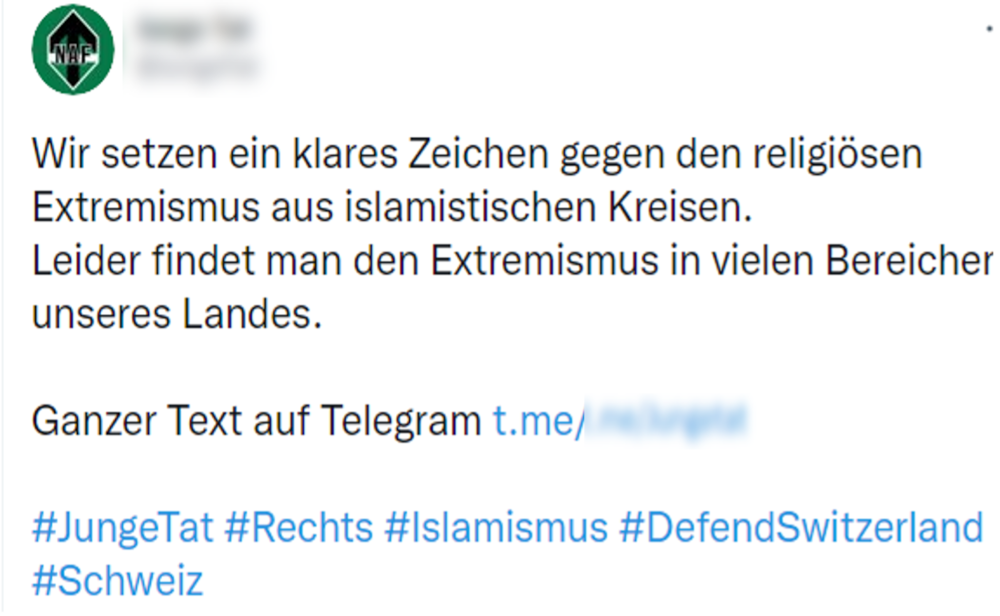

Likewise, in the Tweet below Junge Tat direct their followers to their Telegram channel in order to read their full message.

Figure 13

This way, by posting slightly more moderate content on mainstream social media platforms, and then re-directing users to Telegram, where more extreme content is hosted, groups have effectively circumvented mainstream social media platforms’ moderation attempts and continue to recruit and radicalise other young people on these platforms. As such, violent extremist content remains readily available on mainstream social media platforms. Indeed, when conducting research, the authors discovered extremist accounts by merely following platforms’ algorithms for recommended users.

Young extreme-right users value having a presence on mainstream social media platforms, as they play a key role in enabling them to spread the word about their movement, and recruit new people into their groups. As opposed to simply moving to new platforms or ecosystems, young extremists have taught themselves how to bounce back.

The current mechanisms through which these groups are continuing to recruit young users on platforms such as Instagram, Twitter and TikTok merit urgent attention. Platforms must play their role in minimising extremists’ ability to reach out to and recruit youths, even and (one could argue) especially when the ones doing the recruitment are young people themselves.

To learn more about the different ways in which young extremists are recruiting their peers into their movement, read our report here.